For a long time, my idea of a British Education, from the safe distance of post-colonial Nigeria, always came through the lens of English language. After all, there is a reason colonialism itself was conducted through the language, and why – over the many years after colonialism – we over here have yet to arrive at any other consensus language with which to conduct government and other communicative business. This changed in one day, last week, which I spent traveling around Cardiff, the Welsh capital, in company of Jeremy Grange, a reporter for the BBC on whose invitation I had arrived at the city to meet with a few people, and understand the development and use of Welsh as not just a medium of instruction and a language of governance, but also a language of education through which the small country has found and is expressing its individual identity in that entity called Great Britain.

From the bilingual signs at the Cardiff Central train station, the visitor is welcomed into the city with a reality that although this is still part of Britain, an old empire that once ran the globe with one language (and plenty boots on the ground), one was entering into another realm where the role of English is at best complementary. And not only were the bilingual signs everywhere, the first language on each sign was always Welsh, followed by English. For a foreigner coming from a place where – even with its over 521 languages – one would be hard pressed to find a bilingual sign on the streets, it was quite easy to be shocked and disoriented. This, as the mind reminds over and over, was part of the Great Britain. Yet one is asked to contemplate bilingualism as a normal fact of life.

From the bilingual signs at the Cardiff Central train station, the visitor is welcomed into the city with a reality that although this is still part of Britain, an old empire that once ran the globe with one language (and plenty boots on the ground), one was entering into another realm where the role of English is at best complementary. And not only were the bilingual signs everywhere, the first language on each sign was always Welsh, followed by English. For a foreigner coming from a place where – even with its over 521 languages – one would be hard pressed to find a bilingual sign on the streets, it was quite easy to be shocked and disoriented. This, as the mind reminds over and over, was part of the Great Britain. Yet one is asked to contemplate bilingualism as a normal fact of life.

Not too long ago, in the eighties Nigeria when I was growing up, it was commonplace to be punished in the schools for speaking in one’s native language within the school premises – a fact I realised, to my surprise, was once the case in Wales too in the 19th and early 20th Century. Referred to as the Welsh Not, wooden signs were placed on the necks of students who used the mother tongue within the school premises. This was transferred among the erring students until the end of the day when the last student with the sign on their neck got punished. In my 80s Nigeria, ALL the students who spoke Yorùbá (in my case) were punished, and this was done with the support of most parents. I’ve mentioned in many write-ups (see Speaking the Machine in this Farafina Issue) about how my father’s dramatic intervention in my classroom one day changed my perception of this policy and set me on this current path. But not many parents pushed back. The result today is a generation of people to whom the mother tongue is at best a tolerable nuisance and at worst a hinderance to their career success.

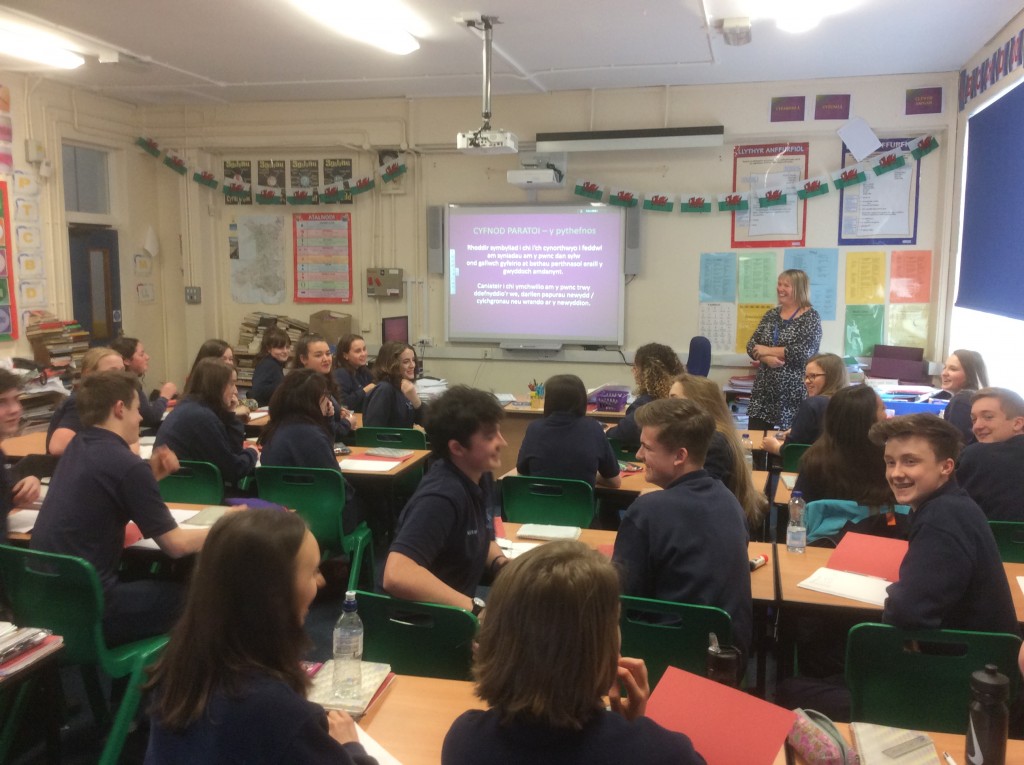

My day in Wales took me first to the Radio Cymru (and Radio Wales), which both broadcast to mostly Welsh audiences. The former does fully in Welsh, and I was able to meet a producer and some presenters, and to also listen in on a live show. The latter broadcasts in English to the same audience. I then went to a Welsh-medium high school Ysgol Gyfun Gymraeg Glantaf which is one of the largest of such schools in the country. It was a great time interacting with the students, both in classroom environments and at lunch with the principal, learning about their motivations, their experiences with the Welsh medium (especially those from English-speaking homes), and their hopes for the future. It was a wonderful and enlightening experience. In the evening, I had lunch with Jon Gower, a notable writer in the Welsh and English languages whose work and years of experience had a lot to teach me about the role of the mother tongue in asserting a cultural identity. I intend to write more about these experiences, in detail, in coming days.

No Comments to A Night in Wales: Of Bilingualism in Britain so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)

No one has commented so far, be the first one to comment!