I read an advanced copy of Bassey Ikpi’s new memoir a couple of weeks ago, and I haven’t stopped thinking about how important it is that the work exists in the world. I wrote an earlier review much of which I’ve now discarded for focusing less on the unique nature of Ikpi’s intervention in the space of writings about mental illness than about its similarities — or otherwise — of other books of its nature.

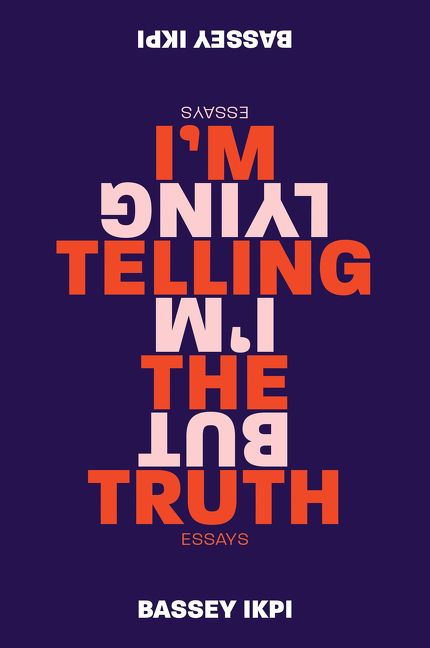

Bassey’s book of essays, titled I’m Telling the Truth but I’m Lying focuses on the writer’s life and upbringing, first as an immigrant child in an America she didn’t immediately adjust to, then as a young adult unable to name the mental issues that afflicted her, and into an adult that had to fight and struggle through the most destructive phases of a bipolar disorder. This summary, however, does no justice to the beautiful piece of literature that is Ikpi’s book. It is a memoir (don’t let the “essays” tag fool you), written mostly in first person, except when — in a style deliberately designed, perhaps, to help the reader simulate the rollercoaster nature of the writer’s journey through the ailment — parts were written in the second person, allowing the reader to pretend, for a second, to be a participant in the ordeal.

The book is honest, though the writer warns us in the title and in many other parts of the book, not to take her too seriously as a reliable narrator. It is raw and unflinching. It peels back an often opaque veil to show the extent to which people suffering ailments of this nature can go in order to feel “normal”, and extent to which mental disorders contribute in the blurring of lines between self-destruction and self-awareness.

“All my life, I feared being “bad.” I already felt broken, already felt like there was something irreparably wrong with me, the least I could do was coat myself in the “goodness”: this idea that who we are is based on how we are seen I already feel broken; I followed the rules but now I wanted to feel something different– to feel better, to feel unbroken–more than I wanted anything else. I wanted something other than this Novocain and numbness. Its very name revealed its power: I wanted ecstasy.”

Page 93.

But more than a confessional — it skips mention of a number of specific personal details on the writer’s professional life, so those looking to learn about the writer’s illustrious career as a travelling artist on the Spoken Word circuit through America will have to wait for another book — Ikpi’s book is a kind of map for those interested in learning about how mental illness affects people. “If I were a nurse or a teacher,” she tells me in a private conversation “It would have shown up the same way.”

And yet, it is not a grim book, because we know that the writer survived to tell the story. It is not a morality tale either. Let me quote Erin Wicks, an editor at Harper Collins here: “What you will find within these pages is something far riskier and far braver: a human breaking down her external wall to show us the structures beneath, and then examining them before our very eyes with great honesty, and love, and brutality, and rawness, and vitality, and mourning.”

I have interviewed Bassey Ikpi in the past, when she lived, briefly, in Nigeria in 2014. She continues to be an advocate for openness in speaking about mental illness. To a layman, especially in Nigeria, all mental illnesses are the same. In most African cultures, there is just one word for them: an equivalent of “mad”. In literature, and in reality, there are many dynamics and diagnoses, one not looking the same as the other. Dysthymia is not bipolar disorder, which is not dissociative identity disorder, which is not schizophrenia, which is not chronic depression. So, through the experiences of others, written — in this case with Bassey’s book — with prose that is as honest as enchanting, one hopes that the reader can build both a bank of knowledge and a muscle for empathy.

It is to our benefit that works like Ikpi’s exist and continue to put the conversation right before our eyes. While the illnesses may never quite cure, the result of the human will to thrive in spite of it, as evident in this beautiful book, is a spectacular reward of its own.

I’m Telling the Truth But I’m Lying will be out on August 20, 2019

One Comment to Bassey’s Literature as Truth; Truth as Literature so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)