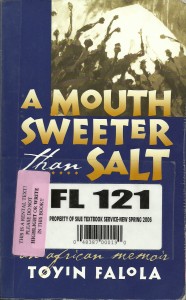

On Wednesday, we spent much of the hour discussing the third chapter of a book of fiction titled “A Mouth Sweeter Than Salt” by  Toyin Falola which is our second class text. In many ways, the book is much like Wole Soyinka’s “Ake”, in style, content, and value, especially in the clever turns of phrase, eloquence, and reference to recognizable landmarks in the history of South-Western Nigeria before independence. The chapter is set when the author was nine years old, and the whole work is written in a way that makes it seem that we are listening to a child talk, even though we know that it is an adult relaying his many interesting experiences from childhood.

Toyin Falola which is our second class text. In many ways, the book is much like Wole Soyinka’s “Ake”, in style, content, and value, especially in the clever turns of phrase, eloquence, and reference to recognizable landmarks in the history of South-Western Nigeria before independence. The chapter is set when the author was nine years old, and the whole work is written in a way that makes it seem that we are listening to a child talk, even though we know that it is an adult relaying his many interesting experiences from childhood.

The third chapter dealt with the author’s first train trip in the 1950s from Ibadan to Ilorin, and his adventures on the streets as a beggar’s boy. He had started school, yet he could not resist a chance to ride on a train which was then a novelty in town. In the end, even though he didn’t have the train fare, he found himself in the belly of the electric “snake”, as he called it, delighting at the wonder of the European invention. As soon as he was discovered to have been riding without a ticket, he was dropped off somewhere along the way, and he found that he was in Ilorin, all the way from Ibadan, and he was loving it. Soon he became a “beggar’s stick boy”, holding the stick for one of the many fake blind men on the streets of the town who begged for alms in lieu of decent work. That job, which provided him with stipends on which to survive, and plenty adventures on the street, ended on the day he mistakenly spoke in English to a postman, wondering if he could send a letter home. Even though he was dirty and looked totally ragged, his grasp of the language shocked both his fake “blind” boss who immediately dropped his end of the stick, and fled as far as he could so as not to be arrested, and the postman who immediately grabbed the boy, and promptly drove him back home to Ibadan to the arms of his bewildered parents and neighbours. It surely reminds of some parts of Soyinka’s “Ake.”

I am convinced that the reason why this book is a recommended text is because of its many descriptions of Nigerian, nay Yoruba cultural life, especially before and during colonial times. The author was born in the 50s, and he grew up in a less educated environment than, say, Wole Soyinka(who was born in the 30s, yet had a whole library of books to read before he even went into school for the first time.) But in the end, there were so many questions raised than could be answered in that one class even though we tried very hard: Why did the boy find the train strange? Why did the postman take him home instead of to the police? Why was a boy not immediately embraced when he got home, instead of being suspiciously viewed by family and neighbours as some form of emere who was born only to torment his folks? Did children beg for alms a lot on the streets of Nigeria? How much of human sacrifice did the Yoruba believe in? Do they still sacrifice people to make money? What is the punishment for such a crime? What is the Justice system like? Do they hang condemned criminals in public or not? Do children have toys to play with? Do you have Amusement Parks in Nigeria? Do you have Six Flags in Nigeria? How come some people do not know/remember their dates of birth? Do you know yours, Traveller? etc.

Every day, I discover new reasons for the perceptions and misconceptions (many of which are justified) about Africa and it cultural practices. Every day, I learn new things about the influence of literature, and the power of words. And every day, I find new reasons why this programme is one of the best, and most useful projects of the American government, in helping us to understand better the world in which we live.

1

Anonymous at http://YourWebsite

Most of their questions amuse me.Thank God this kind of programme is being organised. I know most of them still see Africa as a kind of jungle where there is no effective system of justice and order. They need to know more about our culture

Posted at October 2, 2009 on 2:46am.

2

Adeleke at http://YourWebsite

I found myself trying to answer the questions. Am yet to read “a Mouth…” and will be looking for it.

Posted at October 6, 2009 on 11:24pm.