Once upon a time, before I ever learnt to write a single word in any language, I was just a little son of a published poet. He was not always a poet to me however. He was just a man who embodied several characteristics at different times. Most times, he was just a voice on radio every Saturday. Over a period of time, I was known all around the neighbourhood of my upbringing as the son of so-and-so-the-poet-the-broadcaster. Most of those times, it was an annoying tag to have not just because it didn’t say who I was as a person but a reflection of someone else’s shadow, but also because in calling my name that way, they called unnecessary attention to me that I always sought to escape. There was no way I could enjoy the privacy of a harmless gathering of mates in a public gaming centre without being spotted and called out, like a public property: “Oh, K-the-son-of-the-famous-writer-poet-the-broadcaster. How are you today? What are you doing here? Where did you leave your shoes?” In many ways, those kinds of hide-and-seek from known faces defined my childhood, and I always swore to change my name sooner or later, either removing the connection to the-poet-the-broadcaster as a way of proving myself, or modify it in a way that left me the freedom first to be myself. I am sad to say that the scheme has not worked to total perfection, but I sometimes delight in the conceit of its pseudo-ingenuity.

One day then, last year while applying for the Fulbright programme, I included a short anecdote of my father’s bold and brutal intrusion into my private bubble of innocence while I was young and impressionable at about seven years of age, and how that little act of defiance that he exhibited in the presence of us in class that day somewhat defined my attitude to language. What I didn’t know while writing the essay in which I had deliberately refused to mention his name was that it was not just going to be read by the American Fulbright board, but the Professors of Yoruba in the Foreign Languages department of my host institution, whose decision it would be really whether or not they wanted me in their University. Those whose essays were not impressive enough were dropped at that stage of the application. I got wind of this little gist only three weeks ago when I invited Professor A. into my language class to both assess the students, and to share a little of his experience in teaching Americans the language. Big mistake! Along with the knowledge he said he had possessed all along of the content of my Fulbright application essay, he told the whole class of how he was able to decode from what I wrote that I was K-the-son-of-the-famous-writer-poet-the-broadcaster even though he didn’t know me as a person, as well as some other flattering stories of how rich in culture the man’s works are, and how he and many in his (the professor’s) generation had grown up in Nigeria reading my father’s published Yoruba poetry publications, listening to his poetry music albums and reading his books. While the professor spoke, and I listened silently in the corner, the students all looked in awe as if there was a sudden new knowledge being bestowed upon them about the young man who’d been with them all along without having disclosed this crucial part of his person, and once in a while they cast their sights towards where I sat grinning.

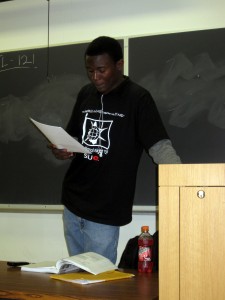

From then on of course, they troubled me to come to class with poems both from my father, and some from myself, and I warned them with apologies that if they were to listen to the poetry of this man in original Yoruba, the music would probably be the only thing they’d be able to enjoy, and nothing else. They agreed, and said that I’d been dishonest to have held out on them for so long a time while they told me many things about themselves. I felt guilty, went to my apartment and printed out stuff that I always kept for my own amusement, and we spent the next class listening to me read from some of the poems I had written, some from long ago, and some from recently. I also read for the first time in public, an English translation of my father’s famous love poems which I had done in 2002, and they were thrilled. One person asked if the poems were written for my mother, and I answered in truth that we like to believe so, even though the fact is that they were written long before both of them were supposed to have met. I guess that’s for him to explain.

From then on of course, they troubled me to come to class with poems both from my father, and some from myself, and I warned them with apologies that if they were to listen to the poetry of this man in original Yoruba, the music would probably be the only thing they’d be able to enjoy, and nothing else. They agreed, and said that I’d been dishonest to have held out on them for so long a time while they told me many things about themselves. I felt guilty, went to my apartment and printed out stuff that I always kept for my own amusement, and we spent the next class listening to me read from some of the poems I had written, some from long ago, and some from recently. I also read for the first time in public, an English translation of my father’s famous love poems which I had done in 2002, and they were thrilled. One person asked if the poems were written for my mother, and I answered in truth that we like to believe so, even though the fact is that they were written long before both of them were supposed to have met. I guess that’s for him to explain.

Today, on the internet – the main reason for this post, my first literary translation effort was rewarded with a publication. I got involved in this project through a tip by friend and poet Uche Peter Umez. Hard and daunting as it looked at first, I had the task of translating a poem, Volta, written in English by Richard Berengarten, into my native Yoruba. I am finding out now that the work was translated simultaneously into seventy-five languages, including Ebira, Pidgin, Igbo, Ibibio and Hausa which, along with Yoruba, are also spoken in Nigeria. I feel quite privileged to have participated in the project because it also offers some encouragement to my reluctant muse about the prospects of literary translation – mostly of thousands of lines of poetry, this time from my native Yoruba tongue into English, for the benefit of a larger world audience. It also gives me the benefit of somehow finally being able to lay claim to being K-the-poet-translator-himself-in-person. But maybe it’s true that a goldfish has no hiding place. Ask me, I’d rather be a hummingbird.

Find the project here.

9 Comments to Oh, K-the-Poet so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)