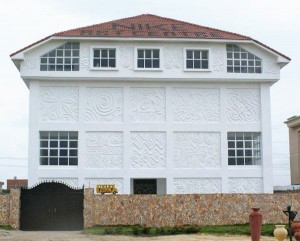

Her reputation had preceded her, so whenever I drove past the junction from where one can see the tall white building with Nike Art Centre written boldly on its roof as if trying to attract the attention of a flying helicopter, I promised myself to one day drop by to see what the building housed. From afar, it promised treasures. As opposed to other buildings in the area, it was painted white, and designed with art reliefs from top to bottom. Remarkably, the white reliefs made it an impossible structure to ignore even from a distance away. A re-routed path from work found me in front of the gallery last week, and I walked in.

Her reputation had preceded her, so whenever I drove past the junction from where one can see the tall white building with Nike Art Centre written boldly on its roof as if trying to attract the attention of a flying helicopter, I promised myself to one day drop by to see what the building housed. From afar, it promised treasures. As opposed to other buildings in the area, it was painted white, and designed with art reliefs from top to bottom. Remarkably, the white reliefs made it an impossible structure to ignore even from a distance away. A re-routed path from work found me in front of the gallery last week, and I walked in.

At close contact from outside, the white relief on its walls portrayed a relaxed artistic atmosphere. In an otherwise bustling part of town off the Lekki-Ajah expressway, a conspicuous art edifice was always going to be a sight for sore eyes. Outside the compound, there was a white bus on which was the artist herself, along with a few other women from different countries, all dressed in native Yoruba tie-and-die. For a sixty-one year old woman, the cheerful youngish face she put on the bus offered a gentle reminder of the rejuvenative power of creativity, and promised a kind, friendly encounter. I took a few pictures of the bus and the general periphery of the premises, silently convinced that at any moment, someone was going to show up and challenge me for taking pictures unannounced outside a famous gallery. No one did, and I entered the compound.

Inside the wooden fence, to the right, was an elevated wooden platform that looked like a performing stage. There were a few people there, including a grown man that I would later find out to be Chief Okundaye, the artist’s husband. At that moment however, I was content to greet them, and to ask if I was on the right path to the receptionist of the gallery. “Go in,” someone said, and I did. There was no power, and the only source of light in the huge ground floor of the building was the setting sun, coming in from the front door and another one down the hall. But there she was, right at the “reception desk” as soon as I entered.

She was in a small talk with a young man who sat across from her. “Good afternoon Mrs. Okundaye,” I said, half flustered that she would actually be in the building at this random moment of my unplanned visit. “E pele o,” she responded, as warmly as she had smiled a few minutes before on the white bus parked outside. For a few moments, I was confused. Should I just go sit down and chat with her, or should I talk to this other young woman now coming towards me to ask what I was looking for. I decided on the latter. “I am a blogger,” I said, and I’d always planned to come here and see what it contains. Do you think you could show me around and answer some of my questions?” Sure, she said. A few seconds and a few short steps later, I asked her whether I could take pictures. She didn’t seem sure. Why don’t you ask her, she said, pointing back to Mrs. Okundaye where she sat, now on the phone with someone. What a good idea, I responded, and followed the direction of her finger. I sat down by the table beside the young man who was now scanning through a copy of the Punch newspaper.

On the phone, Nike (as I will call her now) was coordinating an art party for young children in Kogi state. “Yes,” she responded to the person on the other line. “Buy some noodles for five thousand naira and make sure that the children are able to eat and that they are all satisfied. I will transfer the money to you in a few hours.” She went on for a while, while I share glances with the young man who seemed to have been enjoying an earlier conversation, and is now entranced by this new one. When she got off the phone, he resumed his. “You are such a mother,” he said. “Why are you feeding them this time?” She responded that it was one of her outreach programmes with underprivileged kids of the town. They are fed, and then given a canvas and other painting materials to work with. The best of the artworks produced at the show are then sold in order to make some more money to send the children to school.

She was genial and soft-spoken, if only slightly older than the picture on the bus. But it was a hot day, and the heat from my perspiration – having walked some distance in the afternoon sun to get there – may have added to the general warming ambiance. Much of what I knew about her until this moment was anecdotal, but all very heartwarming. A textile artist from Kogi state came from practically nothing, but through hard work, drive, and persistence, became one of the most famous names in Nigerian art. “I know only of two women artists from Nigeria,” a professor colleague at the University of Ibadan once told me in the words of another artist colleague she had met somewhere in Europe, “Nike Davies, and Nike Okundaye.” The European had no idea that Nike Davies and Nike Okundaye was the same person, separated only by the circumstance of a second marriage. When I told her a few minutes later that I was from Ibadan, she wasn’t bashful. “Where in Ibadan? My first husband is from there. Do you know Agbeni Ile Olosan?”

When she eventually knew my purpose in the gallery, and my delight at finding her there on my first visit, she waived all regulations against picture taking, and asked the young lady to show me around. “Take all the pictures you want. I will also like to show you some of our photo albums. And there is other information online…” In the photo albums, there were pictures of Nigerians as well as foreigners who had come to the gallery and some other exhibition of hers. In one of the pictures, she was greeting Nigeria’s former president Olusegun Obasanjo. “We have exhibitions all the time,” she said. In some other picture, I saw the other galleries in Kogi, in Abuja, and in Oshogbo. This one in Lagos, she said, is the largest. The young man chipped in that the Lagos gallery where we were housed the largest collection of artworks in Africa. “And that is not counting all the ones that are still locked away in storage.”

I took a few minutes off from where we sat, and walked around the gallery with the young woman attendant. She knew a bit about the place, the names of some of the famous artists that had exhibited their work here and elsewhere, and other relevant information about Nike Okundaye herself. One level of stairs after the other, we talked about each painting or sculpture, she gave me a little back story of each of the artist, and we went on. The building had four storeys and a penthouse-like storage room at the top filled with hundreds of little sculptures that bore remarkable semblance to ancient Benin arts. It crossed my mind to ask if Mrs. Okundaye’s husband did artwork too or if he is from Benin or had anything to do with the gallery itself, but I didn’t ask. A few minutes later while talking to Nike about my observation about the range of work hanged all around the gallery, she helpfully told me that her husband was a retired serviceman. It didn’t satisfy my curiosity, but it put some perspectives on my perception of him.

He came in at some point during my stay on the reception chair, on his way to another room on the ground floor. Nike introduced us, and I rose to greet him. “Oh, so you’re Yoruba?” he asked. “Are you a lawyer?” No, I replied. “So why are you in suit on such a hot evening as this?” I laughed. He seemed serious, but he didn’t wait to get a reply. But I answered him anyway, that I was a teacher, and that my job required me to dress formally at least while in the premises of the school. I thought of his name, Okundaye, but never managed to ask Nike how it is pronounced. Dialectal variations on imported speech may have been more responsible for the varying ways I’ve heard it pronounced, yet I’d struggled between a rendering of it as “the rope gets to earth” – an extension of the Yoruba myth of creation, or “the sea becomes the world” – something which, although I don’t fully understand it, might have a fascinating history of its own.

I asked Nike about her influences and her level of satisfaction with her progress and success so far. She, in turn, thanked God for the opportunity. Her influences, she said, come from the stories and cultural norms and art of the Yoruba people. Geckos, she pointed out, have always been vehicles of stories and proverbs. They are in every house – even in a poor one – and they perform a service to their hosts by eating up all the insects and pests. You would find many of these animals in my tie-and-die fabric arts, she said. “There have been roundabouts in Yorubaland,” she said, “long before colonial times. We have ‘orita-meta’, and ‘orita-mefa’, etc. These were descriptions market women used to designate places where they met. If you look at this work on the wall,” she continued as she pointed to a huge stretch of fabric art framed on the wall, “you would see instances of both roundabouts and geckos, and many more. These are reflections of story-telling patterns of the Yoruba. I am a fabric artist, and a storyteller.” I remarked that I may have seen one of her works at the Pulitzer in St. Louis. She said they had actually expressed interest in acquiring an even larger work of hers – the one now hanging on the wall.

I hung around her table for a few more minutes before I took my leave. She gave me her card and asked me to call on her if I ever wanted any more information. I had had an unexpectedly pleasant afternoon in the presence of someone who is not only a very talented artist but also a kindhearted human being. She gave me access to the whole gallery, answered all my questions, and posed for several shots of my camera. If I ever decide to hold an exhibition of anyone of my photographs in Lagos, I will certainly consider using the inspiring insides of that beautiful place. I didn’t tell her that as I walked out back into the hot Lagos sun, but it wasn’t necessary anymore. She already made clear the large extent of her open heart.

* Two days later, I lost my camera in a taxi, and along with it all the pictures I took at the gallery.

** First published in the Guardian (Nigeria) on November 30, 2012.

No Comments to Meeting Nike Davies-Okundaye so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)

No one has commented so far, be the first one to comment!