Here are my thoughts on the final story on the Caine Prize shortlist for 2013: Chinelo Okparanta’s America. Thoughts on earlier stories are here: Bayan Layi, Miracle, Foreign Aid and Whispering Trees.

_________________

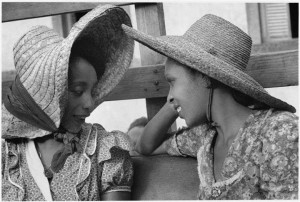

As far as the Caine Prize shortlist is concerned, no better gift could have come after last week’s unimpressive encounter with Whispering Trees than a story that is unpredictable, sweet, and delightful – a worthy end to my review of the five shortlisted stories of the Caine Prize 2013. In Chinelo Oparanta’s beautiful story of love and longing is that final elixir. It is a tale of love between two women, eventually separated by the other by the Atlantic Ocean, hence “America”, and a story-long attempt through a stream of recollections to reunite with the distant lover.

The story begins in medias res with the heroine Miss Nnenna Etoniru on the way to Lagos from Port Harcourt for a visa interview. She is hoping to head to America in order to meet Miss Gloria (whose age we didn’t quite figure out), a subject of her affection and love which had defied parental objection and entreaties. Before the trip is over, we hear about her first visit to the visa office which ended in a rejection. We also hear of the story of the relationship itself, how it began, who knew about it and what their reactions were, and what Nnenna was looking forward to in the nearest future. They had met in a school she worked, and where Miss Gloria had visited for a week, and struck up a relationship away from the eyes of their colleagues and the world. All through the story – and to great credit to the writer not falling into a temptation to write a treatise – the word “lesbianism” was never mentioned once. Instead we had the following:

The story begins in medias res with the heroine Miss Nnenna Etoniru on the way to Lagos from Port Harcourt for a visa interview. She is hoping to head to America in order to meet Miss Gloria (whose age we didn’t quite figure out), a subject of her affection and love which had defied parental objection and entreaties. Before the trip is over, we hear about her first visit to the visa office which ended in a rejection. We also hear of the story of the relationship itself, how it began, who knew about it and what their reactions were, and what Nnenna was looking forward to in the nearest future. They had met in a school she worked, and where Miss Gloria had visited for a week, and struck up a relationship away from the eyes of their colleagues and the world. All through the story – and to great credit to the writer not falling into a temptation to write a treatise – the word “lesbianism” was never mentioned once. Instead we had the following:

“Mama still reminds me every once in a while that there are penalties in Nigeria for that sort of thing.”

The “sort of thing” taboo-speak the author used here and elsewhere enhances the sense of the abominable in the relationship, leaving us to resolve our feelings about it ourselves. In another scene where her mother walks in on a live sexual scene taking place in Nnenna’s room, the writer describes it again as follows:

“Mama stands where she is for just a moment longer, all the while she is looking at me with a sombre look in her eyes. ‘So, this is why you won’t take a husband?’ she asks.”

It is subtle so that all concerned know what the mother had just witnessed. This dexterous show-not-tell style of writing greatly benefited the story, and deserves a lot of commendation. It also ensured that the story had just those (barely) two sexual encounters in order – I would guess – to keep it special/relevant enough to matter in our minds before it became all too gratuitous. In another scene, she describes something that seemed like a woman on her period:

“There is a woman sitting to my right. Her scent is strong, somewhat like the scent of fish. She wears a headscarf, which she uses to wipe the beads of sweat that form on her face. Mama used to sweat like that. Sometimes she’d call me to bring her a cup of ice. She’d chew on the blocks of ice, one after the other, and then request another cup. It was the real curse of womanhood, she said. Young women thought the flow was the curse, little did they know the rest. The heart palpitations, the dizzy spells, the sweating that came with the cessation of the flow. That was the real curse, she said. Cramps were nothing in comparison”

It turned out eventually that there was a literal fish somewhere in the woman’s bag, and that the woman herself was pregnant. It seemed to be a special narrative strength of the writer to put things like this, or else a personal quirk derived from her own inability or reluctance to be anything but discreet with intimate subjects. I found it enchanting.

In response to the earlier-quoted charge, Nnenna responds:

“It is an interesting thought, but not one I’d ever really considered. Left to myself, I would have said that I’d just not found the right man. But it’s not that I’d ever been particularly interested in dating them anyway.”

This is where my fascination with the plot begins. Many questions arise: was Nnenna a lesbian or merely bisexual? Was she capable of ever loving a man the same way she had loved Gloria? Was Gloria the last woman she would ever love (it certainly sounded like she was the first, or we would have been told)? Is it a love based on mutual respect of mental and professional capabilities and idealism, or one fuelled by lust and desire? Is it both? Will it endure or has it already begun to fail by the time Gloria returned home for the first time after her initial departure? Is this story about an expression of sexual orientation bursting out of a repressed environment or an expression of just a particularly stimulating and enduring passion developed serendipitously for one person only? Not all of these can be answered by the quote above, or by the story itself. At the end, we are left with the endless possibilities that abound in the reunion of two distant friends in a foreign land.

I am curious about these because the story is an important intervention in the current debate about same-sex relationships. From all we know, it was a consensual relationship. But from what we hear of the interventions of Mama, it was one caused by the overbearing influence of the foreigner which Nnenna just couldn’t shake.

I am curious about these because the story is an important intervention in the current debate about same-sex relationships. From all we know, it was a consensual relationship. But from what we hear of the interventions of Mama, it was one caused by the overbearing influence of the foreigner which Nnenna just couldn’t shake.

I found Mama‘s presence very interesting too: a Nigerian woman of the conservative Igbo culture whose strongest reaction to her daughter’s same-sex relationship was to cry a few times, and to pick out baby names in order to pressure the daughter. No church interventions. No village elders brought in. No shouting out loud until the whole town got involved and shamed the daughter. Either she is a weirdly tolerant modern Igbo/Nigerian mother, or she is a contrived flawless character that exists nowhere else but in Ms. Okparanta’s rebellious imagination. Either seemed to work perfectly, but I can accept this only because I am creatively wired to do so. It might be harder for others.

On the other hand, female-to-female sexual love seem to occupy a lower run on the outrage ladder of our society than male-to-male. The writer seemed to have acknowledged that reality in this scene, a nod to the more familiar types of Nigerian families we have come to always expect to meet in these kinds of situations:

‘You know. That thing between you two.’

‘That thing is private, Mama,’ I replied. ‘It’s between us two, as you say. And we work hard to keep it that way.’

‘What do her parents say?’ Mama asked.

‘Nothing.’ It was true. She’d have been a fool to let them know. They were quite unlike Mama and Papa. They went to church four days out of the week. They lived the words of the Bible as literally as they could. Not like Mama and Papa who were that rare sort of Nigerian Christian with a faint, shadowy type of respect for the Bible, the kind of faith that required no works. The kind of faith that amounted to no faith at all. They could barely quote a Bible verse.

‘With a man and a woman, there would not be any need for so much privacy,’

************

I enjoyed reading the story because of how it is written, error-free as you would expect from something in Granta, and the dimensions of politics, policy and advocacy that formed a humming background to the whole relationship. The right balance was struck to keep them visible enough, but not too loud as to crowd out the other details in the story. When the story is over, we forget about the oil spill and the other issues bedeviling Nigeria or the US, and are just contented that lovers are finally going to unite.

My grouse with America is with the title, an attempt to be plain and simple that ended up terribly as trite at best, and patronizing at worst. Out of about a million other titles that evoke love, expectations, guilt, distance, longing, and a thousand more other emotions one must feel while being in a taboo relationship fraught with such perils, Chinelo chose “America”, the biggest buzz-kill of all. The theme of “America”, “Americanah”, or traveling or returning has been written about so many times that inviting the audience into that story on that premise holds too much risk. I had the same problem and a disappointment of expectations with Pede Hollist’s “Foreign Aid”. One had to read the with a much reduced of expectations only to discover a gem in the end. That is too cruel, and doesn’t do justice to a work that could otherwise have enticed more curious readership and a better whetted appetite for such interesting stories.

_____________

Reproduced on Nigerianstalk LitMag | Photos from Actuatornic and Queer Cinema.

3 Comments to No, Not “America”, but Love – A Review so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)