Last week, between November 18 and 22, writers and thinkers converged on Abeokuta for the second edition of the Ake Arts and Book Festival. It was also my second time of participating in the event, but the first as a guest. For some reason, the organisers thought it important this year to involve a linguist with but a finger or two in the literary pie in a festival of poets, writers and other makers of creative ideas. (Fake modesty out of the way, it was a beautiful, engaging, and stimulating event of which I was glad and proud to be a part). On Thursday the 20th, I gathered fourteen students from Whitesands School where I currently teach English, along with a colleague and award-winning journalist Bayo Olupohunda, into the school bus and headed to Abeokuta.

The drive to the quiet rockhill town north-east of Lagos has always been a delight, at least the second leg of the journey that begins on the Abeokuta-Owode Road. The Lagos-Ibadan expressway is still under construction and subject to surprises in the form of potholes, narrowed lanes, broken down vehicles, and diversions. For someone meant to host a Book Chat at 10.30 am on that same day, the choices are limited. One either leaves Lagos as early as possible so as to avoid all traffic-related delays, or sleep in Abeokuta in one of the luxurious hotel rooms already booked for guests at the Festival. If one is a teacher in a high school, traveling with students who have been brought to school by their parents and need to be returned to school on the same day; and particularly if one is a husband of a working wife, with a nine-month old baby who one would terribly miss if one were to take the second choice alone, the choices become hard.

The drive to the quiet rockhill town north-east of Lagos has always been a delight, at least the second leg of the journey that begins on the Abeokuta-Owode Road. The Lagos-Ibadan expressway is still under construction and subject to surprises in the form of potholes, narrowed lanes, broken down vehicles, and diversions. For someone meant to host a Book Chat at 10.30 am on that same day, the choices are limited. One either leaves Lagos as early as possible so as to avoid all traffic-related delays, or sleep in Abeokuta in one of the luxurious hotel rooms already booked for guests at the Festival. If one is a teacher in a high school, traveling with students who have been brought to school by their parents and need to be returned to school on the same day; and particularly if one is a husband of a working wife, with a nine-month old baby who one would terribly miss if one were to take the second choice alone, the choices become hard.

We were supposed to head out of the school by 8.am, but by almost nine o’ clock, we were still stuck in Ikoyi traffic. By even the most conservative calculations, we were starting to be late. I began to worry that I might miss my session. The author I would be chatting with, notable columnist, journalist, professor, and novelist, Okey Ndibe, had just returned from the United States a couple of days earlier. How could someone from the US arrive earlier in Abeokuta than someone who lives in Lagos? How disappointing. Lola Shoneyin (poet and author, organiser of the Festival) would be even more disappointed, I thought, as I urged the driver to speed up as much as he could within sensible limits. By 9.30, Lola started tracking me via text messages. I assured her of my location, and pleaded that if I didn’t show up on time, my panel be swapped for someone else’s. She assured that if the worst happens, we’d postpone it for an hour. A few minutes later, a tweet went out that our book chat would begin at 11.30am. That was a relief.

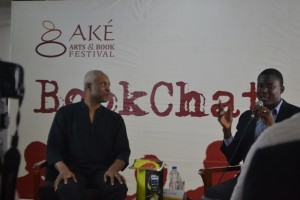

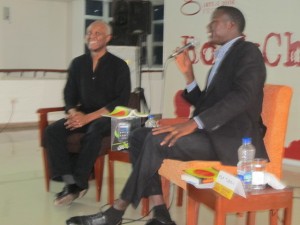

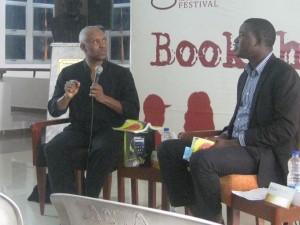

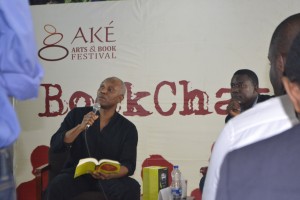

We arrived at the June 12 Cultural Centre, venue of the event, at about a quarter to eleven. Fifteen minutes later, I was in the hall meeting Okey Ndibe for the very first time. Weeks before, I read everything I could find about him on the internet. Some I’d read before, some I was reading for the first time. His life, work, and opinions have made him an interesting person and personality in the Nigerian literary and political space for a very long time. Conversations with other friends and colleagues about him have also guided me into a number of relevant points of inquiry. Our Book Chat was going to be one hour of conversation in front of a room full of writers and festival goers. Okey is a simple but dignified man, as his poise, dressing, and personality immediately showed. While he chatted with a few other folks around the hall, I glanced at a few of the questions I had prepared. His latest book Foreign Gods Inc is a fast-paced thriller of many layers of social and political commentary. I had two copies, one on my kindle, and one hard copy which a couple of my students had developed an attraction for on the way to Abeokuta. On arrival at the venue of the Festival, Lola Shoneyin hinted to the students that two of them would win an electronic tab for thoughtful questions.

One hour went by like a flash. As I’d been told of him, Okey Ndibe engaged each question with the thoughtfulness and breeziness of a seasoned professor, with humour, friendliness, tact, dynamism and thoughtfulness. Why did he dump on James Hardly Chase so much? What does he mean by Achebe saving him from Chase? How did he meet Chinua Achebe and what was the relationship over the years? What does he mean by Nigeria not having a real national character? What is “an ethnicity of values” anyway? What influenced him to write Foreign Gods Inc.? Any influences from the real life event in Soyinka’s autobiography of having to sneak into Brazil so as to kidnap a supposed stolen god? How would Professor Ndibe like the book read: as an ethnographic material on African people, or as a migrant literature, like Chimamanda Adichie’s Americanah? How has the reception been so far? Would he like to read a part of the novel to the audience? By the time it was over, the seats had been filled, and the applause was genuine. I had a great time, and so did the students. Questions were asked, by the students and by other members of the audience, and we were done. Two students won tablets for their questions (and the rest were mad at me for not calling them when their hands went up. We resolved it on the way back to Lagos).

One hour went by like a flash. As I’d been told of him, Okey Ndibe engaged each question with the thoughtfulness and breeziness of a seasoned professor, with humour, friendliness, tact, dynamism and thoughtfulness. Why did he dump on James Hardly Chase so much? What does he mean by Achebe saving him from Chase? How did he meet Chinua Achebe and what was the relationship over the years? What does he mean by Nigeria not having a real national character? What is “an ethnicity of values” anyway? What influenced him to write Foreign Gods Inc.? Any influences from the real life event in Soyinka’s autobiography of having to sneak into Brazil so as to kidnap a supposed stolen god? How would Professor Ndibe like the book read: as an ethnographic material on African people, or as a migrant literature, like Chimamanda Adichie’s Americanah? How has the reception been so far? Would he like to read a part of the novel to the audience? By the time it was over, the seats had been filled, and the applause was genuine. I had a great time, and so did the students. Questions were asked, by the students and by other members of the audience, and we were done. Two students won tablets for their questions (and the rest were mad at me for not calling them when their hands went up. We resolved it on the way back to Lagos).

***

A few other questions went unasked, because of time: What’s the relationship with Christopher Okigbo and his family? He was afterall the keynote speaker at the Ohaneze Ndigbo event in Belgium in honour of that important poet about two years ago. Okey, being a young boy during the Biafran War, remembered a little of it, detailed in his essay My Biafran Eyes, how deep was that experience in shaping his upbringing? What does he think about language use in African literature? As a child of a culture with dying languages all around, how does he think that this can be reversed? Which writer in his generation does he consider an influence? What of older generations? And younger ones? He’s working on “An African Doing Dutch in America” – a memoir. What can he tell us about that? When will it be published? What was his experience as a Fulbright scholar teaching at Unilag? What inspired his first novel Arrows of Rain? He currently teaches fiction and African literature at Trinity College in Hartford, CT. What’s it like there? Has he stopped being harassed by the SSS at the airport?

***

The students split up and attended one more session. In the session involving the president of the Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA) Professor Remi Raji and author Yejide Kilanko, which was well attended, one more student won a tablet for his thoughtful question to the author. He seemed very pleased. Their day being sufficiently made, not only by their winning of electronic tablets but the idea of meeting and chatting with world-famous authors and learning a few things they hadn’t heard about before, they headed to lunch downstairs by the festival bookstore before heading back to Lagos. There a few of the students met with some other writers, chatted them up about stuff, took autographs, bought books, and generally took in the festival air.

The students split up and attended one more session. In the session involving the president of the Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA) Professor Remi Raji and author Yejide Kilanko, which was well attended, one more student won a tablet for his thoughtful question to the author. He seemed very pleased. Their day being sufficiently made, not only by their winning of electronic tablets but the idea of meeting and chatting with world-famous authors and learning a few things they hadn’t heard about before, they headed to lunch downstairs by the festival bookstore before heading back to Lagos. There a few of the students met with some other writers, chatted them up about stuff, took autographs, bought books, and generally took in the festival air.

In the bus on the journey back, conversations ranged from the shock of realizing that their English teacher was a relevant enough person to have been invited to take part in a book festival (“You never told us that you were a writer! What book have you written? Aren’t you Mr. Olatubosun? Why does it say Kola Tubosun on the guest list? How did you know Okey Ndibe, Lola Shoneyin, and all these people? Do you know Wole Soyinka too? Where is Wole Soyinka anyway? Why isn’t he ever here when we’re around? among others) to the choice of theme in writing (“I write too, you know, but I never knew that one could be famous by writing African stories”, “Are you serious that people will buy your work if you set it in the Nigerian environment rather than abroad?” “I never knew that. All my characters have English names.” “How do I get published?” “Would you read my work?” “Can I come next year? Alone?” etc).

The most heartwarming comment followed later, halfway into the trip homewards when lethargy and torpor had us all but sprawled around the seats: “If I don’t make it into the final list of students coming here next, or after I leave school a couple of years from now, I’ll try to find my way to the next Ake Festival, or another one in the future.” Seems like a comment that the organisers will thoroughly enjoy. In the end, the decision to bring them along seemed like a great idea.

____________

Photos courtesy of self, Akefestival.org, and Chidera Ezeokeke, and Tamilore Ogunbanjo

One Comment to Memories from Ake (i): Okey and the Students so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)