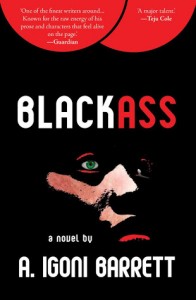

Author: A. Igoni Barrett

Nos of Pages: 302

Publisher: Kachifo Limited. 2015 (Under its Farafina imprint)

Review by Femi Morgan ___

Furo Wariboko wakes up and begins to come to terms with his new identity. He was a black man yesterday and he is a white man today. Furo is born again without confessing away his blackness totally, his black ass is the constant reminder of the disappeared melanin. This Kafkaesque novel is about the metamorphosis of not only Furo but also Furo’s people in a postcolonial state.

Furo lives in a cosmopolitan landscape which despite its aspiration to compete with its western counterpart fails in the infrastructural, socioeconomic decimals of true metropolis. The author splendidly subdivides Lagos using the perspective of exotic prediclection towards white people. The people who live in Ẹgbẹ́dá, where Furo lives, are not conversant with a white man walking on the streets and hustling up and down. Furo, therefore must find a way to escape the eyes of people. Areas like Victoria Island and Lekki have white people jogging in the early hours of the morning. White people live within these scapes as expatriates, government personnel and as facilitators of linking the values of the west in the globalisation project of Africa. Igoni Barret captures the nuances of Lagos most accurately. He spares no time in explaining the rich as well as the struggling transits of the city. His exposition on Lagos is successful because it is a subtle brush on the landscaping of the exciting narration.

Furo begins to receive an umbrage of responses to his new personality. A white man is shown exceptional favour at the detriment of a fellow black man, a white man conveys the aspiration of so many poor Africans and therefore taxi men and transporters hope to get a piece of the dollar-pie by jerking up the price. Many people hold conversations with him, asking him about the places he has never been, the places in Europe and America.

Furo is a white man with a black soul. He is expected to negotiate this displacement of identity with a certain ingenuity that may make or mar him. These postcolonial reactions of reverence, of hate, of anger and of fear stem from a deep postcolonial malaise that has been enhanced by stories of the great west as against the low global north. Thus the author satires Africa, it is a continent that kneels in the presence of its western personas.

The thirty-three year old Furo earns a job that he had sought for 10 years. He is given the benefit of doubt when he bungles a crucial question at an interview and he is placed in a rather uppity position in Haba! a failing enterprise, because of his white status. Arinze, the CEO of Haba! says in an interview with Furo, ‘I will be frank with you, we need a man like you in the team’. Meanwhile, despite the change of skin and hair, Furo is a typical Nigerian. He hardly reads for leisure or for self-education, he is an educated ‘good for nothing’, a half-literate whose chances in life has improved not because he is intelligent but because he is now white. Yet, his Nigerianness haunts him, he is an African who is unable to reach the fullest of his potential, he is an educated rag who is fighting a ‘postcolonial war’ that has long been lost.

I do sympathise with Furo because I realise that the older one gets, the more he realises that he has shed those dreams and gifts of his childhood. A jobless 33-year-old will often be misunderstood because he has not crossed the essential threshold set by society. In Nigeria, a child is like a cheque that must never bounce, he must make the parents proud and must become the symbol of ancestral progress.

Furo understands that no family member will understand his metamorphosis and this leads to his departure from home. He struggles with his new identity, the necessity for departure and the nostalgia of motherly love. Mothers subtly own their children by sheer investment, so much that they become the essential mention in the cannon of one’s personal narrative. Furo’s father is typical. A man overwhelmed by failures, losing his pride as he tries to be faithful to his family. The novel explains that despite his dehumanisation by circumstances beyond his control, his staying will be vindicated in the memories of the hereafter. Furo’s father lives by a certain mechanical routine of hopelessness, a television addiction and a dictatorship that stems from his inability to provide for his family. These postcolonial times calls manhood to question, the manhood is shrivelled because it often times has failed to be successful and has failed to meet the expectations of family and friends.

Now a white man wants to eat fufu at a buka for disoriented black people. It reminds me of Bright Chimezie’s song about the musician eating Akpu in the streets of London. The Europeans invited the police to rescue Chimezie from committing Suicide. Furo is a victim of the eczema of modernisation, yet he is watched as a circus, while he expertly swallows lumps of fufu. He is favoured against his fellow black man with an extra meat for his exotic performance.

Igoni is a splendid storyteller whose sense of observation leads his story to those existential paradigms that we often fail to acknowledge. He is not preachy, not assertive, he tells a story that pulls you in. Igoni’s work is a classic, a story that stays in your subconscious and becomes part of your memory. You walk the streets with Furo, you experience the sun shining on his face, you make love to Sycreeta, you become his alter ego. You ask yourself, is it better to live an interesting, conspiratorial life than to live a life of a cockroach?

Igoni brings to fore a new prism of narrative for contemporary writing, it is close to reality because the conversations transit between the cadences of English, popular lingo, tweet-speak and introspective expressionism. Igoni’s prose gives the reader an impression that storytelling is an easy craft, but a second look at how he wields the story and how he brings himself into the story, you realise that Igoni has painted a monumental Chiaroscuro with words. He tells a story of a failed cosmopolitan ideal as he creates parallels and binary oppositions that make the work come alive. Sycreeta and Tósìn are women who want different things from Furo, Arinze and Yuguda, Lagos and Abuja, Furo and Frank Whyte, black and white. Igoni is not the storyteller in the book, ‘he’ is in the novel, changing to a ‘she’ with a dick between her legs. Nevertheless, I come to glean the authorial intrusion of the writer whenever he postulates about existential ideas in the novel. This however is a trademark of the many classic novels that predicates on explaining the workings of modernity and life, like James Joyce’s A Portrait of An Artist As A Young Man and Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis.

There is a realistic sense in which many of the characters are trying to transition from a certain physchological in-betwenness to a full knowledge of their persona or an attempt at accomplishing their dreams . The reader becomes aware of the way of the world from the novel. The things we shy away from using the veneer of religiosity are challenged by the comprehensible raison d’etre of the characters. There is Sycreeta who understands the prize of a white man’s worth and plays a game to win, there is Yuguda, Arinze and others who realise the impressions that a white man can bring to their firms, their NGOs and Ad Agency. So the jobless 33 year old becomes the most sought after. There is Victor Ikhide and Ehikhamenor in the novel, a resonance of reality meeting fiction. Ehikhamenor retains the high status of being an artist while Victor Ikhide is a talkative, loud-mouthed driver. Yuguda is clearly the Dangote of the novel.

Furo’s changes is in continuum, he becomes more opportunistic and begins to negotiate his identity and to create the money spinning perception that lands him a better deal. Furo tries to be complete in his whiteness but it is left to Igoni to let him achieve his new ambitions as a white man.

_______

Femi Morgan is the co-curator of Artmosphere, a leading Arts and Culture event in Nigeria and a co-publisher at WriteHouse Collective. He is a co-recipient of the 234Next Fashion Copy Prize and was longlisted for the BN Poetry Prize in 2015.

One Comment to Beneath the Black Ass is a Continent so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)