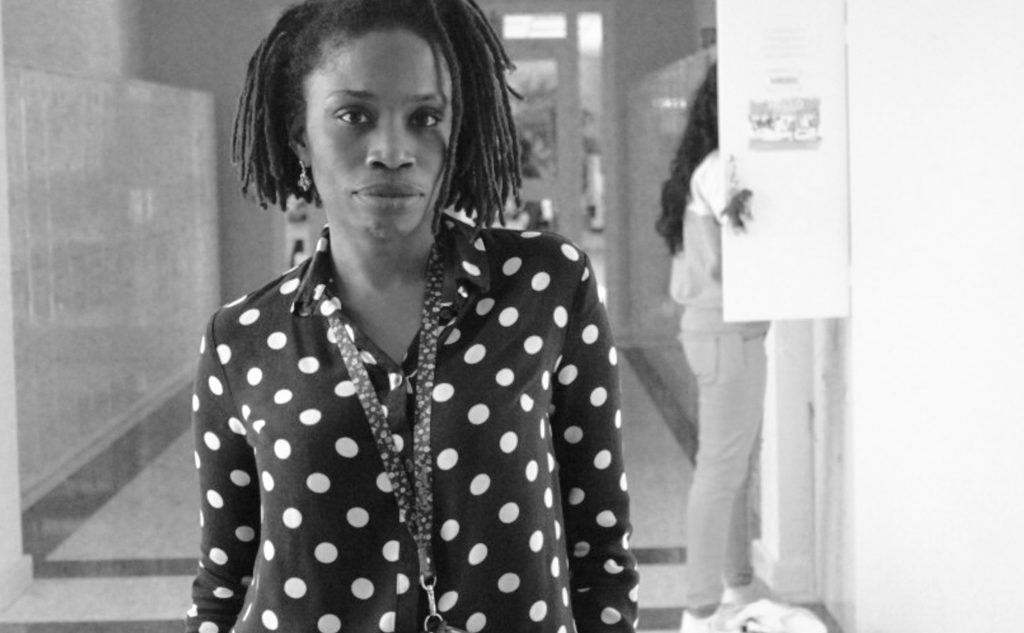

The Invisible Borders “Borders Within” road trip has begun. Every week, I’ll bring you a conversation with each participant. Two weeks ago, I spoke with Emeka Okereke and Emmanuel Iduma. Today, I speak with Zaynab Ọdúnsì, an award-winning photographer who also works as a full time lecturer at Dar Al Hekma University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. She holds an MA in Photography from the University of the Arts London and was the recipient of the residency award by the Mairie de Paris and Cites International des Arts- Residency in 2006. Enjoy.

________________

Wow, you live in Saudi Arabia? That certainly pops out instantly. From the scratch, what misconceptions do you think I need to get out of my mind immediately?

Yeahhh I have lived here for over 9 years now. I would say the prevalent misconception people have of women in KSA as a direct result of the Western media’s agenda to perpetuate this laughable perception would be the one to disregard. Saudi women don’t hide behind a veil – they don’t stay hidden away – they hold positions of power in both the private and public sectors. Sure we all have to wear an abaya (it can be any colour and design you want it to be and we spend ridiculous amounts of money on them.

Which one, particularly, would I be shocked to find untrue or unsubstantiated?

That all Saudis are loaded. That you have to walk around in black and covered. No, women absolutely do not have to wear hijab, the head covering.

But do you have to walk with a male relative before you walk in public?

I wish you could have seen my face when I read this question. Bwahahahahahaa. Oh mannn I forgot that was yet another big Saudi myth. Noooooo you do not have to go out in the company of a male. That is so far removed from the truth I go out with my friends all the time. I guess the fact that women are not allowed to drive (yeahh boo hiss big time to that) we always need a driver but they just get in the car and go where we ask them to take us. Exactly like women do in Lagos all the time – we have drivers and there’s always Uber, husbands, brothers we don’t care who just as long as they well.. just drive us wherever! Be it to work, uni, restaurants, the beach, friends’, the malls… sure I would like the choice to drive myself but actually I quite like not driving. But no I don’t need to be “in the company” of a man in the capacity of a chaperone.

How did you find yourself in the Middle East, anyway? What do you do there, and how has it been?

My husband studied Arabic and his job brought us here all those years ago. I started working at a very progressive all women’s private university where I teach the photography courses in the school of design and architecture. Basically the introduction to darkroom (yes!), alternative processes, and the digital studio photography courses.

The British school that my kids attend is exceptionally good – I live on an expatriate compound with families from all corners of the world. Cost of living is low and for a wild weekend Dubai and Abu Dhabi are a couple of hours away.

I don’t really do things I don’t like to do so I will say it’s been great. Of course it’s not for everybody – you know, women still have to abide by rules of modesty in public and for some this can feel restrictive. I mean you can’t walk around Jeddah in shorts and a bikini. I have many close Saudi friends and met more people from different nationalities than I ever did living in the UK or Nigeria. My kids don’t know anything else so to them for now at least this is home.

I have many close Saudi friends.

What languages do you speak at home, especially to the children? Have you ever worried about them losing access to their mother tongue as a result of this distance?

I speak Yorùbá fluently but sadly only speak in English to my kids at home and they pick up Arabic from school and our neighbours on the compound.

I think the fact that my husband doesn’t speak Yorùbá (German/British) compounds it.

Do I feel sad that they don’t speak or at least understand it? yes big time. But we all know about language and kids – I think one or two long summers in Nigeria over the next few years and they will pick it up. To be fair I didn’t really speak a lot of Yorùbá growing up I just found myself in my late teens realising that I was completely fluent. But saying that, I was living in Nigeria until my mid teens and was exposed to the language.

As a photographer, what is your biggest challenge working in such a conservative country where the public (I’d mistakenly written “pubic” at first) gaze is not always a welcome presence?

Lol. Pubic eh?

Challenges are twofold. As a photographer – the biggest challenge for me like most working mums is juggling work and family commitments, this compounds the dilemma of me actually finding time to do my own personal (creative) work. Language used to be a major barrier but not so much anymore. I am not really a street photographer so I guess it’s easier for me. The way that I now approach my work is more about long term projects that can unfold without being intrusive.

As a teacher, I have students that produce really compelling highly personal work but due to the conservative nature of their backgrounds many of my students’ work is usually for my eyes only – for assessment. They do not even go in my course files. This can be frustrating at times when I want to share the work with colleagues or organisations that would be truly moved by their originality and novelty.

I’ve taken a look at your site but couldn’t understand what you were doing? Tell me more about the Hekayat Ashara photography project .

So after years of living in Jeddah I went with some students to an area called Al Ruwais district, which is known for its multicultural multi ethnic residents. It is also has a notorious reputation as a no go area. Rumours of drugs, prostitution etc are rife and in the government’s sight for “rejuvenation”. Inhabitants of Ruwais make up the lowest income earners in Jeddah.

So I launched a community based project called Hekayat Ashara (The story of 10) where 10 women of different nationalities/backgrounds living or working in Ruwais were given photography workshops in order to document the area before the proposed changes. We met every week and paired each Ruwais lady with one student from the school of design and architecture over a 1-year period. The project was hugely successful with proposals for a second edition in the Holy City of Makkah.

Your bio says you’ve worked for British Airways, The Nigerian Conservation Foundation, and Guaranty Trust Bank. Can I ask what you did for them as a photographer?

British Airways were sponsors of an “Expedition of Goodwill” to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the birth of Richard Lander and to celebrate the Lander brothers’ in November 2004 to retrace their historic river journey. I was hired to follow and document their experience.

Guaranty Trust Bank sponsored and renovated a school called St. George in Ikoyi and I was hired to make some images of the school and the kids during this transition period for their annual reports and other in house purposes.

Hired by the NCF to travel to Gashaka Gumti national park – photographs for promotional materials.

As a photographer, what do you look for in a scene? What kind of environment most inspires you to reach out for the camera?

As you rightly asked about the notion of the gaze living in a country where I don’t really have the opportunity to go around pointing the camera around I tend to plan my shoots in advance. I don’t stumble upon a scene – I always somehow have to orchestrate what unfolds in front of my lens. This means that I spend more time planning props, location and especially lighting. Of course the downside is that I miss out on the spontaneous potential of the medium. This is what I am most excited and nervous about the road trip – the fact that I have to produce work on the go. Looking for these elements that I usually meticulously plan every day on the go in a new city everyday.

What has been your most memorable experience as a woman working, either in the UK, in Nigeria, and in the Middle East, either in comparison or in contrast?

My fondest memories or experiences as a female photographer I would say was definitely during the active years of the collective Depth of field. Working in a group it always felt like a welcome change of perspective to get the input of the guys (Uche, Zulu, Emeka and Amaize).

I just go about my work though usually – my gender is inconsequential most days.

What is your favourite work and why?

I like different work for different reasons – some for what I learned about myself, some for what I learned about others. I am very fond of the work that I did with the very popular traffic warden opposite Law School years ago.

How did you get into the Invisible Borders Project?

I have known Emeka for years – we are members of the collective Depth of Field and the worked together on projects in the past. I had been planning to join the IB road trip for a few years now but work commitments never made it quite possible. Luckily this year it’s worked out and I am really excited to be a part of the borders within edition.

What is your biggest expectation for the trip?

My biggest expectation is producing meaningful work as being a university lecturer, great emphasis is placed on research. and I am hopeful that collaboration especially with the writers will support and help me with my writing to support the research-based body of work I expect to produce.

What is your biggest fear?

I have a few worries mostly related to hygiene, staying clean, but for sure my biggest fear on the road trip is falling sick. My kids are worried about mama getting taken by those bad guys!

If I interview you again at the end of the trip, what do you expect would have changed either in your appreciation of travel, your craft, or Nigeria in general?

Honestly I’m not too sure. But sure I won’t be the same Zaynab from 45 days before. I love travel and I am not naive as to think that travelling is easy. I know that we must rely heavily on the mercy of our creator to bless us as we pull into every new city. I pray that we will encounter people that will be merciful and kind to us – people that will help us on this seemingly crazy adventure.

I hope more than anything that people will see the value of such projects and be driven to support more readily in the future.

Thank you for talking to me.

Anytime. Thank you!

___________

Photos from Invisible Borders.

2 Comments to “I Don’t Stumble Upon a Scene” – Interview with Zaynab Odunsi so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)