by Dèjì Tóyè

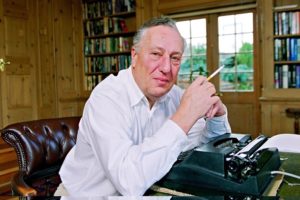

The first Brexit ideologue I met in flesh and blood was not as dramatic as the foul-mouthed Nigel Farage or mop-headed Boris Johnson. The novelist Fredrick Forsyth was at the Cambridge Union Society to talk about ‘the 7 Pillars of Freedom’ a pretty dainty title for a talk about the future of the UK in Europe. It was in the late autumn of 2013 and Forsyth, himself now in the autumn of his life, was a character from a different era. The Union hall which filled up to the brim and spilled into the lawns when crowd pullers like Jesse Jackson or, as I understand, Julian Assange visited, was sparse on that occasion. I even got a front-row seat in the motley crowd that occupied half an aisle of the hall. As I made my way to that event, Forsyth was for me still an image—that young reporter whose career took off with his coverage of the Nigerian Civil War in the 1960s, whose reportage of that event challenged official British policy much earlier than most analysts’ and whose two books on the war would become as important as any other in the much controversial historiography of that war. In short, I was going to hear this internationalist with an expansive view of the world. But oh, what autumn does!

‘The 7 Pillars of Freedom’ was really a nativist treatise on how only the Anglo-Saxon world now holds the hope for true democracy, and freedom, in the world. And, oh, how Europe is gradually dragging Britain down the path that leads away from all that. Although, in my view, many countries across the world would check the boxes of the so-called 7-pillars, Forsyth did not believe what passes for democracy in the rest of Europe and much of the world (he has interesting things to say about Africa, by the way) meets the mark. The speaker also papers over the fact that Britain does not balance two of the pillars well—that is, the Pillar of ‘Elective supreme power’ (elective executive government) and ‘Election by constituencies’, at least not as well as in her ‘Anglo-Saxon’ peer, the US, where both popular and electoral votes are better balanced in the direct choice of the executive authority. This should have been warning signal that democracies are not all the same. After all, Aristotle may not even recognise as representative of democracy a gathering where all eligible men of the town are not congregated in the agora, caviling all day.

Forsyth’s performance in Cambridge has something to say about the way the Brexit campaign had been carefully curated over the years. Farage may fume and curse in the European parliament, and Boris Johnson may scare the hoi polloi with the immigrant bogeyman, our speaker knew well enough to strike a more dignifying pose before this debating society, appealing rather to the finer, if somewhat exaggerated, elements of the British heritage. Subliminal in Forsyth’s speech – made to the more politically aware of the students in this university that, together with Oxford, has produced all of UK Prime Ministers with university degrees, bar four – was a reminder of ‘the good old days’ when all of Europe was fascism or socialism and Britain ‘alone’ spread the light of freedom and democracy from the Atlantic to the Pacific (never mind that that itself rode on the tailcoat of imperialism).

That last point is important because Forsyth’s ostensibly more elevated argument also papers over the possible economic consequences of an ‘exit’ decision. It has been suggested that Britain got a better deal in the world when it was not constrained by the collective bargaining of the common market. What is forgotten is that the status quo ante has changed. The old empire has since disappeared and even that feel-good replacement for it – the Commonwealth – has now weakened. India, Britain’s most important colonial legacy is itself now a world power in both economic and technological terms (it launched 20 satellites into space in the last few days). China, that other Asian power, has since repossessed Hong Kong, the British Pacific holdout. Against the colonial dependency paradigm, the biggest European trading partner to Nigeria, Britain’s most important colonial haul in Africa, is, wait for it, The Netherlands.

But the UK has made its decision anyway. And as an avowed political determinist, I support it, just as I supported the Scottish referendum and even mildly wished the separation campaign won, if only to reinforce my belief that, as I stated then, a nation is an argument and not an axiom. It is a lesson for Nigeria and other struggling political inventions of, well, say Britain.

__________

Dèjì is a lawyer and creative writer, based in Lagos.

No Comments to Encounter With a Brexiter so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)

No one has commented so far, be the first one to comment!