I haven’t read many books about travelling around Nigeria written by Nigerians. No doubt they exist (and readers should please recommend some for me in the comment section). I have however read many about traveling in other parts of the world. Tẹ́jú Cole’s (2016) essay collection comes to mind as well as Wọlé Ṣóyínká’s memoir You Must Set Forth At Dawn (2006). There is also America Their America (1964), an “autotravography” by J.P. Clark which caused controversy for what critics thought was a narrow and judgmental view of American values. Recently, there is Okey Ndibe’s Never Look An American In the Eye (2016), an autobiography, and many more.

There are however many more narratives written about the country, and about the continent, by visiting (foreign) journalists, writers, novelists over the years. Karen Blixen‘s Out of Africa (1937), JMG Le Clezio’s Onitsha (1991) and VS Naipaul’s The Masque of Africa (2010) come to mind easily. But so does this one. The overall impression of such books has always been the worry that they rarely depict reality as is, but only as perceived by the visiting foreigner, which – to be fair – is the whole purpose of the subjective narrative. I expect that the impression of America I’ll get from reading travel notes from an African visiting the US in the 1960s will give me an idea of America through that writer’s perspective of events as they unfold to him/her.

Even in the online space, one might easily find blogs written by foreigners about travel around the continent than one might of blogs by Africans of travel experiences in their own continent. (This is changing, of course. You’re reading this on a travel blog managed by an African, after all). But why is this the case? Human civilization itself is an experiment in travel, documentation and adventure conditioned by necessity, curiosity and sometimes nationalism. We have always left our comfort zones for new experiences. And, as archaeology and anthropology tell us, we have always documented those movements, even unconsciously, in hieroglyphics, and oral poetry, tribal marks, and lately in writing. In the 21st century Africa, the prevailing narrative is that travel for leisure and travel writing is a Western chore, done by the privileged few, and those conditioned to it by their profession in journalism.

Reality, unfortunately, seems to bear it out for the most part except in some rare cases. Olábísí Àjàlá was a Nigerian student who found himself in the United States at age 18 in the late 1940s. Having failed to succeed as a medical student at DePaul University, Chicago, he decided to travel through the country to Los Angeles, on a bicycle and document his experiences along the way. Through deportations, skirmishes with authorities, short Hollywood career (including meeting then actor Ronald Reagan), many short-lived marriages, children, and global fame, through the fifties, sixties, and seventies, he became the patron saint of all adventurers, and an icon in popular culture for African travel. Being called Ajàlá Travels in Nigeria today is a homage to his larger-than-life reputation. He also wrote a book An African Abroad.*

So why is it that unless in rare cases Africans are not known globally to document our adventures in writing, or is it that we are just generally averse to travelling for its own sake? My friend and scholar Rebecca Jones has been asking this question for a while. In a conference she facilitated in Birmingham earlier in the year, the Call observed:

“For a long time study of African travel writing in the West has focused on Western-authored travel writing about Africa. But this has ignored both the long heritage of the genre amongst African and diaspora authors. African travel writers have traversed both the African continent and the rest of the world, writing about encounters and differences they meet in their own societies and others. They have engaged with colonialism and the post-colonial world, have produced ethnographic description, reportage, poetry, humour and more. They have traversed genres and forms, from the Swahili habari written at the turn of the twentieth century to Yoruba newspaper travel narratives of the 1920s, from accounts of students and soldiers abroad, to newspapers and today’s online travel writing.”

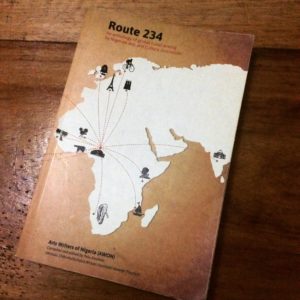

Aside from this blog, there are quite a few other ones online with focus on travel as an African hobby, done especially without the express purpose of becoming a travel “journalist” working for a media house, but for its own sake. Why are there not more. Africans, after all, travel as much as everyone else. Is it that we don’t care about documenting our experiences the way that others do? I have just finished reading Route 234 (2016), an anthology of global travel writing by Nigerian arts and culture journalists, compiled and edited by Pẹ̀lú Awófẹ̀sọ, an award-winning culture journalist. It is a delightful read of many fun, scary, heartwarming, and diverse experience of Nigerians in many different local and international situations. The contributors are however many of the continent’s known arts and culture journalists. This fact will not help our subject matter, but it shouldn’t remove from the value of the book as a necessary work and a delightful read.

According to the editor, the idea for the book came from a private listserve conversation among these culture/travel writers earlier in the decade about documenting some of their travel experiences. It took many years before the idea finally became concrete. The 211-paged book lists Kọ́lé Adé-Odùtọ́la, Olúmìdé Ìyàndá, Ọláyínká Oyègbilé, Èyítáyọ̀ Alọ́h, Mọlará Wood, Steve Ayọ̀rìndé, Pẹ̀lú Awófẹ̀sọ̀, Jahman Aníkúlápó, Túndé Àrẹ̀mú, Nseobong Okon-Ekong, Akíntáyọ̀ Abọ́dúnrìn, Ayẹni Adékúnlé, Fúnkẹ́ Osae-Brown, Sọlá Balógun and Ozolua Uhakheme as contributors. The scope of the travel experiences documented therein covers Los Angeles, Atlanta, Bahia, Juffureh, Accra, Plateau, Nairobi, Durban, Pilanesberg, India, London, France, Frankfurt, Nice, and Holland.

One of my favourite narrative in the work is Mọlará Wood’s “Farewell Juffureh” (page 35), covering a visit to Alex Haley’s ancestral hometown in the heart of Gambia as well as Nseobong Okon-Ekon’s “Trekking the Mambilla Plateau” (page 93). In both, the reader is vividly guided through experiences that must have been much more intense and affecting than words could capture. Some of the others detail culture shocks at visiting a new place for the first time and re-setting their opinions and expectations preconceived from a distance (“Accra Mystic” by Jahman Anikulapo, page 79) while some focus on their immediate task; covering a film festival, for instance (“Film, FESPACO, Ezra” by Steve Ayọ̀rìndé, page 61). A heartwarming one by Ṣọlá Balógun (“The Good Samaritans of Nice”, page 181) describe an experience common to many frequent travellers: being stranded in a strange city after a missed flight.

What the book represents overall is an intervention in a space where much more effort of this nature is needed. But travel isn’t, and shouldn’t be, the preserve of just culture writers and journalists. Writing about it shouldn’t be either. Tourism isn’t a big deal in Nigeria today because of lack of government (and private sector) care, yes, but also because of a seeming lack of interest in the populace itself. As I argued in this recent piece on a visit to historical locations in Ìbàdàn, commercial attention will come when governmental and private sector intervention takes the first step:

“I think back to a recent experience, in Italy, where tourism has built a thriving industry of restaurants, malls, and gift shops around notable structures that tell the country’s history, real and fictional, and how much value that attention (and tourist dollars) has brought to the country. Old churches and abbeys, ancient arenas in Verona and the Colosseum in Rome, among others, are all just ruins of a certain past. But they have been preserved and well branded in order to attract foreigners and their resources. Even a fictional character, Juliet, from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, has a touristy structure built in her honour, called Casa di Giulietta.”

Travel is fun. And even when it is not, it is always an enlightening exercise. As Mark Twain said in The Innocents Abroad (1869), “travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.” That same perhaps can be said about travel writing, if not as a way to reflect on one’s adventures, as a way to keep said experiences in the memory of the world.

The book is a delightful read, but much more is needed.

_________

* There are many other stories like this, no doubt. Ravi on twitter has pointed me out to “Sol Plaatje’s sea travel piece” (by which I assume he means this book, Mhudi, an epic of South African native life a hundred years ago), and Rebecca, in the comment section, to a few more published narratives, also of a few years back. Their input also reminded me of Olaudah Equiano’s equally notable memoir. There are many more like these, I agree. My point is that there are not many more, and certainly not as many notable ones as there should be).

For more reading

8 Comments to Travel as Life: A Review of Route 234 so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)