Abu Dhabi, from distant (and ignorant) estimation, didn’t seem like the most natural place to find a Guggenheim Museum. It’s in an Arab country appearing, at least from preconception, to be necessarily hostile or at best reticent. True I’ve heard great things about Dubai and the progressive nature of that society. But like most things not encountered in the flesh, they remained in the realm of hearsay, hovering around the globally pervasive perceptions of all Arab countries as just one thing: conservative.

But all misconceptions eventually meet reality and knowledge happens. It must be what Mark Twain meant by travel being “fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness.” And so, on my week-long visit to the country to participate in the inaugural Culture Summit, I found myself in the embrace of a Guggenheim Museum. This museum project, and the other involving the Louvre Abu Dhabi, is a collaboration with the government of the United Arab Emirates and prominent culture centres around the world to make Abu Dhabi a cultural centre in the Middle East.

I am not a visual artist. Not since primary school anyway. My contact with and appreciation of the visual arts have stayed consistently close to the familiar activity of gawking, collecting, and critiquing – the latter only in my head and among like-minded friends. I have found solace, many times, in the warm presence of a well-stocked museum or well-curated art exhibition. The environment for meditation that they provide and the visual stimulation guaranteed in a well-lit studio space while observing mounted artworks are unquantifiable pleasures of middle-class life, at least for those to whom that is a worthwhile activity.

And so, when I got a chance to spend some time at the exhibition space holding the temporary collections of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi at Manarat Al Saadiyat, I needed no convincing. This location, on the famous cultural district of Saadiyat Island which hopes to also host other venues of cultural significance like the Louvre previously mentioned, is where much of the activities for the Culture Summit was taking place. One open door away and we were face-to-face with timeless pieces of art as Jacques Villegié’s Quai des Célestins (1965) or Tanaka Atsuko’s Painting (1960).

And so, when I got a chance to spend some time at the exhibition space holding the temporary collections of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi at Manarat Al Saadiyat, I needed no convincing. This location, on the famous cultural district of Saadiyat Island which hopes to also host other venues of cultural significance like the Louvre previously mentioned, is where much of the activities for the Culture Summit was taking place. One open door away and we were face-to-face with timeless pieces of art as Jacques Villegié’s Quai des Célestins (1965) or Tanaka Atsuko’s Painting (1960).

On the first wall to the entrance was Chiinsei Botaichui (Female Tiger Incarnated from Earthly Shady Star), oil on canvas, by Shiraga Kazuo, a work created with “bold swathes of sombre colours with tactile density”. The work, we were told, was created with the artist’s feet, seeking “to liberate his work from the constraints of academic-style painting” and “in order to re-conceive the process of painting as an experimental encounter with materiality and surface.” What appears on the board at times resembles a flying bat, and at others an angel of death. But an amateur art critic – me – projecting his impressionistic sentiments on a modern experimental work offers no new value to what the work already presents. The artist was born in 1924 and died in 2008.

On the first wall to the entrance was Chiinsei Botaichui (Female Tiger Incarnated from Earthly Shady Star), oil on canvas, by Shiraga Kazuo, a work created with “bold swathes of sombre colours with tactile density”. The work, we were told, was created with the artist’s feet, seeking “to liberate his work from the constraints of academic-style painting” and “in order to re-conceive the process of painting as an experimental encounter with materiality and surface.” What appears on the board at times resembles a flying bat, and at others an angel of death. But an amateur art critic – me – projecting his impressionistic sentiments on a modern experimental work offers no new value to what the work already presents. The artist was born in 1924 and died in 2008.

Through the museum space, there are other exhibits, like work by Motonaga Sadamasa, another Japanese artist (1922-2011) whose work used poured paint, depending on gravity to “replace the paintbrush and foregoing the precise and deliberate meditation of the artist’s hand.” The third and final Japanese artist exhibited was Tanaka Atsuko (1932-2005) whose work of Vinyl paint on canvas “evokes the incandescence of the dress (and) intricate network of wires and bulbs reflect (an) interest in (the) technology of wiring systems and lights.”

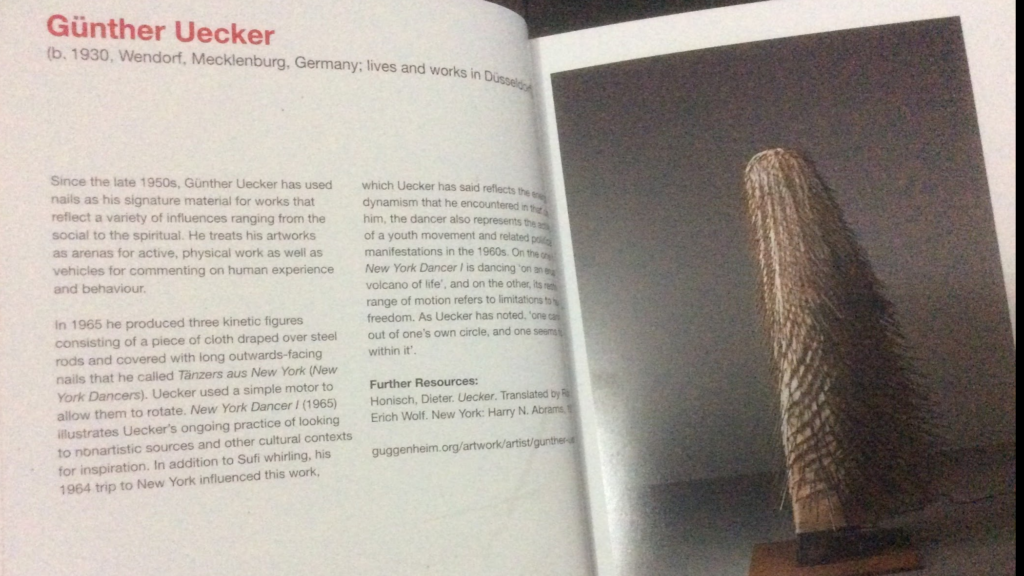

At the centre of the opening space are two kinetic works by two German artists. Gunther Uecker’s New York Dancer evokes the African egúngún without acknowledgment. It is a work “consisting of a piece of cloth draped over steel rods and covered with long outwards-facing nails.” The other, by Jean Tinguely (1925-1991) is called Baluba, a dancing piece of scrap metal “meant to portray a certain craziness and rush in this technological civilization”. Both of them, though not activated at the time but shown through a small television in their kinetic elements, felt familiar in a visceral way that most of the others didn’t. A walk through the Polytechnic Ibadan, or the Yaba College of Technology, will bring the traveller in contact with many similar kinetic and scrap metal artworks of like impression.

Other artists whose work were on display included Niki de Saint Phalle, Jacques Villeglé, Julio Le Parc and Rasheed Araeen. For a temporary exhibition space, it was an impressive introduction. Outside of the museum space, at the reception area where participants in the Summit gathered, there were other artists, from Adéjọkẹ́ Túgbiyèlé (Nigeria/New York) to Jalal Luqman (Dubai) and Cristina del Middel, among others. Here at the Guggenheim, however, very little (except the age of the displayed collection, and a small reception desk) tells the visitor that s/he has crossed over into a new art space.

The most surprising, and most breathtaking work in that museum, however, was Anish Kapoor’s My Red Homeland, an installation that filled a whole room. It was a wax “sculpture” simulating a mound of red garbage stirred continually by a centralized mechanical arm. The description situates the concept of the piece in both the image of blood as well as the colour of saffron, an iconic symbol in India, from where the artist hails. For art enthusiasts to whom Kapoor’s most famous work is The Bean in Chicago, My Red Homeland was a welcome reprise, more impressive at close range, and equally awe-inspiring to the breadth of the artist’s vision and ambition.

I purchased a few fridge magnets on my way out. Something to impress friends and family with. Something not necessarily representative of the scope of the ambition and inspiration of the exhibition just witnessed. Merely representative. The New York Dancer on a fridge magnet is certainly less bewildering as a work unconsciously derivative of ancient African masquerade experiences. But like others, it will mark my refrigerator as a symbol of another place I’ve been, another mind-enlarging artistic experience, not less, not more, than previous others in other parts of the world. But having experienced it in Abu Dhabi, an emerging cultural capital of the world, adds a new dimension not experienced anywhere else.

No Comments to Art at the Guggenheim so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)

No one has commented so far, be the first one to comment!