The Heresiad (KraftGriots, 2017) by Ikeogu Oke is, in my opinion, the most ambitious of the books on the prize shortlist this year. It is a book of what the author called “operatic poetry” (another way to put this would be “poetry in drama and song”) featuring one poem extended over a hundred pages. Yes, one poem. It is epic in its scale, ambition, and character (and even in the words of one of the blurbs. See it:

“It is powerful, and brilliantly composed – a true epic!” – Lyn Innes (Professor Emerita, School of English. University of Kent, Canterbury))

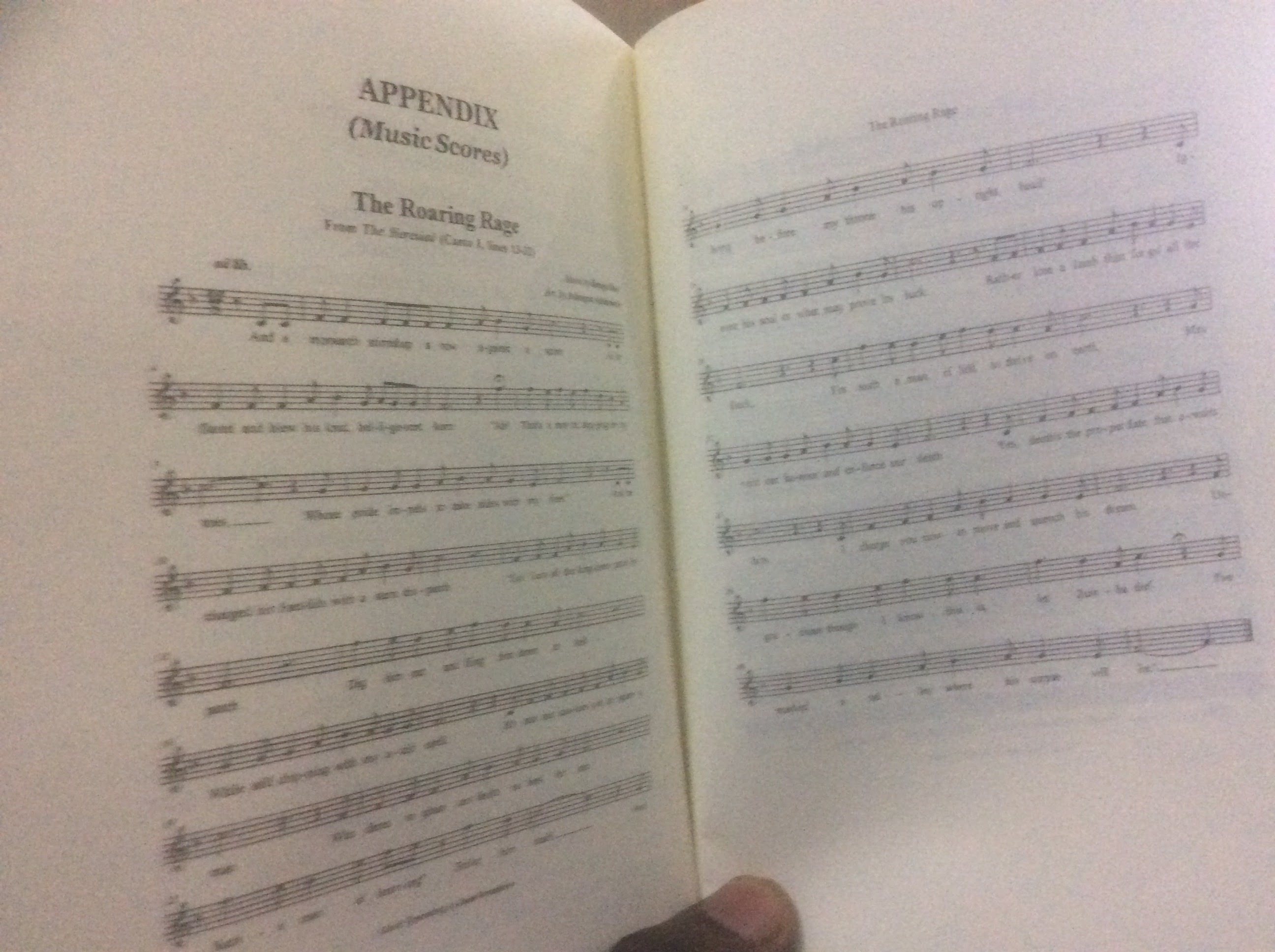

But seriously, the work packs within it a lot of history, philosophy, narrative, culture, allegory, politics, and tradition, rather unapologetically. Without the author’s name, one might confuse it for a work by Shakespeare of any of the writers of the old traditions defined by form, rhyme, and musicality. Only slightly, of course. References intrude from Nigerian (and African) socio-political issues enough to define the work as one addressed to a specific, even if global, audience. And to that idea of musicality, the author graciously provided musical notes with which the poem can be sung.

The name Heresiad, is derived from “heresy” just as the Iliad was derived from “Ilium” or Aeneid from “Aeneas”, as the author explains in the preface. But what needed defending, even more, was the style, operatic poetry, which Oke described as being deliberately crafted as “an art form that transcends verse and goes on to embrace song, music, and drama.” Previous works of this nature which have misled readers into expecting musicality through the use of “Songs of–” in their titles were singled out, from Turold’s The Song of Roland to Vyasa’s The Lord Song to Okot p’Bitek’s Song of Lawino. (He couldn’t have called out Tanure Ojaide’s Songs of Myself, the other book on the shortlist, because this serendipity of both their presence on the shortlist couldn’t have been predicted. But the juxtaposition of this factor in defining Heresiad as unique and better realized as practical literature does appear significant). By discounting the need for a titular nod to musicality and instead embracing it in true form, Oke admits to pursuing a grander ambition: to make written words sing, a homage to Ngugi wa Thiong’o, whose words to that effect was quoted as an epigraph.

Of the thematic preoccupation of the book, Oke says it is written “to make a case for unhindered intellectual and creative freedom… and for mutual respect and harmony between faith and thought, otherwise religion and intellectualism.” In my interview with him, he admitted that the idea of the book, and the first verses in the book, came in 1989 when “a famous writer” was condemned to death for the crime of heresy. He didn’t need to – nor wanted to – mention Salman Rushdie by name, but that connection became immediately apparent. In this book, the condemned author and narrator is Zumba, who was so censured for having writing a “bad” book. To enforce this sentence, and to save him from it, a few other characters, in the person of Reason, Doom, Anger, Sword, Machete, Axe, Stone, Panther, Care, Bluff, Smithy, etc, were introduced with fully-realized characters, compelling presence, and voice. In their thought processes and the unfurling of the curious plot, the poem realizes itself in full glory.

One of the limitations of traditional poetry, which can also become its most enchanting feature, is rhyming. It is a feature that I happen to love. But it is a feature fraught with a lot of risks one of which is the occasional trading of meaning for the benefit of a properly rhyming word, or the use of the immediately available rhyme instead of striving to find the perfect one. In Heresiad, some of these limitations show up, like when “bypass” is made rhyme with “pass”, “reproof” with “proof”, or “unwise” with “wise” (and in one unintentionally hilarious instance, when the native language interference pushes “blade” to rhyme with “head” (page 57). For a book of this type of ambition, it might be that those kinds of lapses are to be expected and tolerated. But for an unlucky book, they can become the flaws by which they are defined.

But when it works, though, it works quite beautifully.

I’m part of this misnomer, I confess,

And so are all you Faithfuls, nonetheless.

Or who among us Faithfuls can have read

The book for which we seek the author’s head?

Rhyming might seem like a trivial issue on which to spend critical time until one realizes that each couplet throughout the work sticks to this rhyming pattern on top of what Oke describes as “lyrical pentameter” (adaptability to lyrical utility). The realization that the author had spent countless man hours crossing all his Ts to achieve this kind of ambitious and thoroughly satisfying theatrical result is most impressive of all.

Now, the author’s plea had reached his ears,

A plea that dripped with anguish and with tears;

And Reason, yes, had pondered through a plan

To take help to the joy-forsaken man.

(page 36)

Equally as impressive is the realization that the book took twenty-seven years to write, over different iterations.

Now lift your voice; lift your voice and say;

Your voice, not mine, must rise and lead the way:

What now transpired among the rising five

Who wished our author more dead than alive?

What – the thought – that, of its own accord,

Changed their common tilt towards discord?

A love as yet profound inspires my choice

To be the human echo of your voice.

(page 52)

Speaking of theatre, when was the last time you read a book of poetry with accompanying musical notations? I certainly haven’t seen any. But here, on page 106-112, the author, with the help of Adéogun Adébọ̀wálé, helpfully guides the future theatre and/or musical director on what is the appropriate way to translate the texts into music.

During my interview with him, I asked whether he would be willing to sing some of the lines to me, and he graciously obliged. It was not as impressive as I’d expected it, but who expects an author of a work to always be its most competent performer? Not me. It is ironic, of course, that this musical characteristic of the work once became a point of risibility when a restless Facebook critic dismissed it as a gimmicky invention to win the $100,000 prize money. On the contrary, I think it is one of the book’s distinctive features, showing it as different as possible from the others on the shortlist in terms of ambition, inventiveness, interdisciplinary scope, and resolve. Now, to see it on the stage!

During my interview with him, I asked whether he would be willing to sing some of the lines to me, and he graciously obliged. It was not as impressive as I’d expected it, but who expects an author of a work to always be its most competent performer? Not me. It is ironic, of course, that this musical characteristic of the work once became a point of risibility when a restless Facebook critic dismissed it as a gimmicky invention to win the $100,000 prize money. On the contrary, I think it is one of the book’s distinctive features, showing it as different as possible from the others on the shortlist in terms of ambition, inventiveness, interdisciplinary scope, and resolve. Now, to see it on the stage!

The author’s habit of including footnotes and references at the bottom of relevant pages irked me at first. They had appeared as an unnecessary usurpation of the critic’s role. But this wasn’t the case. They add a lot of value to the work in illustrating, where necessary, the writer’s influence, allusion, or research. Not one was superfluous.

From what I have observed of the pattern of choice by the NLNG judges, who have typically favoured works of formal and traditional forms in style and ambition (See: The Sahara Testament), I will predict that The Heresiad might take home this year’s prize. There is something about the work that speaks to an intense commitment to innovation, tenacity, joyful experimentation and social commentary in a way that provokes delight and engagement. It is doubly worthy, of course, for its successful bridging of the genres of poetry, drama, and music, while making a strong point, through allegory and an enchanting imagination, about the role of free speech and the responsibility of the writer in a modern society.

I’ll be surprised if the judges disagree, but such surprises are welcome when it’s not one’s work on the shortlist.

______

Find a link to the previous reviews here.

______

Update: October 9, 2017: Ikeogu Oke’s The Heresiad is the 2017 Nigeria Prize for Literature winner. Watch my interview with him here. Congrats to him.

5 Comments to On “The Heresiad” by Ikeogu Oke so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)