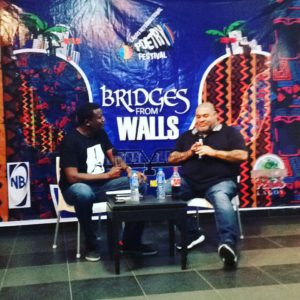

To know Chris Abani is to love him. I spent about an hour today at the Lagos International Poetry Festival interrogating the affable Nigerian/British writer about his life, his work, his vocations, and a few other matters. It was our first ever sit-down conversation about anything, although I had known and admired him for a while, read his work, and exchanged pleasantries when we’ve met at other literary events (last year at the Aké Arts and Book Festival, for instance).

But this time, at a formal setting, I had looked forward to being able to learn a bit more about what motivates him as an artist, and to do it within the stipulated hour. It turned out to be a conversation that was as enjoyable as it was challenging. His reputation, drive, and breath of literary production span an impressive and sometimes intimidating stretch. He is a full-time writer in California, but also an apprentice babaláwo, publisher (and curator of a number of poetry competitions and chapbooks with Professor Kwame Dawes), and author of many award-winning books including Graceland (2004).

There were a number of questions, but one of the most enjoyable parts of the conversation for me was a detour on the true definition of literacy in an African environment. Too often, we have defined literary competence, and even a state of being culturally literate, as merely being able to understand the translation of terms from one language or culture to the other. Whereas, what is true literacy is being able to successfully occupy the full extent of being in that culture and maybe another as well. He mentioned an example of listening to a performance either of the chanting of the Odù Ifá or a poetry performance in Afikpo, where he was born and raised, and being able not just to understand what is being said, but successfully occupying the spiritual and mental state in which the work was conceived and performed. The nearest familiar example from my end would be a literate Yorùbá citizen, listening to a cultural performance with a dozen other not-as-literate people, and having a better, more enhanced experience of the same work of art just because of a capacity to understand the meaning of each talking drum pattern played under each public chant. In Yorùbá traditional art, there are sufficient depictions, as a satire on the importance of this skill, of novice or despised chiefs or kings dancing glibly to a drummer’s feverish patterns without knowing that the drummer was actually insulting them through the delightful ambiguity that the tonal patterns of the Yorùbá talking drums provide.

There were a number of questions, but one of the most enjoyable parts of the conversation for me was a detour on the true definition of literacy in an African environment. Too often, we have defined literary competence, and even a state of being culturally literate, as merely being able to understand the translation of terms from one language or culture to the other. Whereas, what is true literacy is being able to successfully occupy the full extent of being in that culture and maybe another as well. He mentioned an example of listening to a performance either of the chanting of the Odù Ifá or a poetry performance in Afikpo, where he was born and raised, and being able not just to understand what is being said, but successfully occupying the spiritual and mental state in which the work was conceived and performed. The nearest familiar example from my end would be a literate Yorùbá citizen, listening to a cultural performance with a dozen other not-as-literate people, and having a better, more enhanced experience of the same work of art just because of a capacity to understand the meaning of each talking drum pattern played under each public chant. In Yorùbá traditional art, there are sufficient depictions, as a satire on the importance of this skill, of novice or despised chiefs or kings dancing glibly to a drummer’s feverish patterns without knowing that the drummer was actually insulting them through the delightful ambiguity that the tonal patterns of the Yorùbá talking drums provide.

Chris Abani is a truly literate and competent artist in this way, which greatly helped the conversation along. One hour suddenly felt like a few good minutes. But the writer, in spite of his many achievements, also carries himself in a way that is relatable – which is what you’ll expect of someone still intent on learning the very many ways of being, and of existing as a true and competent artist.

I may have ruffled him a bit with an elephant-in-the-room question about a once controversial portion of his biography relating to his imprisonment in Nigeria in the eighties which, a few years ago, put him in the crosshairs of some Nigerian writers who accused him of not just fraud but sabotage: he was portraying Africa in a horrible light for foreigners for his own artistic advancement, and deserved censure. It was an argument that played into the big contemporary hoopla about poverty porn and the perception of Africa in world literature as a nest of ills. In Abani’s response, he gave as strong a defense as one can find for the freedom to be private about elements of one’s life story especially in the face of what he thought was an unfair and relentless attack, and anger at those who he said had tried, though unsuccessfully, to damage his name and livelihood in their blood lust for his scalp through a witch-hunt disguised as a defence of autobiographical fidelity, or the country’s honour. It made sense to me, and I was glad to have given him a chance to defend himself on the topic in a public forum.

What he is known for today, along with his impressive literary output, is his work with the African Poetry Book Fund with Professor Kwame Dawes where dozens of new African writers are discovered every year and published in chapbook and box sets which are sold all over the United States and around the world. His explanation on the breadth of work that the Fund does was thorough and detailed. How he is able to cope with that work along with every other thing he does is one of the wonders of his impressive career.

In the end, I was greatly impressed by the writer as an artist, an important and talented voice in the African writing space, as well as a bearer of important stories.

No Comments to Finding Chris Abani so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)

No one has commented so far, be the first one to comment!