By Deaduramilade Tawak

I decided to volunteer at Aké for the festival this year because I wanted the experience of what it was like to be on the other side. I am not new to volunteering, whether for events or organisations, but if I was accepted, this would be the first time that I’d be volunteering for an event of this type and scale. I had applied to volunteer last year, but was not selected (I went as a visitor, but only on the last day because my leave wasn’t approved), so I wasn’t very hopeful.

Three weeks to the festival, I receive an email from Ify (who is the Administrative Manager for the festival) saying I have been selected as a volunteer. In the email is a document with Terms and Conditions to be signed, but I’m still waiting on leave approval. The document also includes the rules and regulations for volunteers: no chewing gum on duty, no smoking on duty, no asking guests for money or favours, no fighting and so on. Finally, two weeks to Aké, and two days before the deadline for accepting the volunteer offer, I receive confirmation of leave approval, so I print, sign, scan and send the document.

Reinhard Bonnke’s farewell rally will be ending on Sunday, the day volunteers are expected to arrive in Abeokuta for the festival. We decide to leave as early as possible to avoid traffic, but not too early that we’d have to wait hours before seeing Ify, who is in charge of volunteers. We being myself, Afọpẹ́fólúwa, and Opẹ́yẹmí (whom I’d found by asking around for volunteers leaving from Lagos). I’d gone to Abẹ́òkuta myself the year before, and although it wasn’t a bad experience, I felt that I’d be more comfortable if I had familiar faces on the journey.

We leave Lagos shortly after 11am, and I sleep for the entire journey and wake up at the exact moment we arrive at Kuto Park, Abẹ́òkuta, not far from the Cultural Centre where the festival will hold. We take a cab to the centre and meet another volunteer (Ona) waiting. We have 4 hours to kill. Fortunately, I have books, my phone, and three other ladies to keep me company. Slowly, other volunteers begin to arrive. First Yetunde, another first-time volunteer, then Stephanie, another veteran volunteer, and then a stream of young men and women I do not know or recognize.

Ify arrives and we have a “family meeting” where we introduce ourselves — most people are from Lagos, many of us are writers — and are given a quick break down of what the week will be like. Lọlá Shónẹ́yìn arrives at some point. The truck with the books and the other things we’re supposed to sort hasn’t arrived, so we headed to our hotel to group ourselves into rooms. I pick Ona as my roommate. Dinner of jollof rice appears soon after, and we rest a bit before heading back to the venue to help offload the truck. When this is done, we’re each given two orange volunteer shirts, then it’s good nights.

On Monday, we’re grouped into teams, and I’m placed at the registration desk. I’ve been warned by my friend, Ọpẹ́, who had volunteered for the past two events to try to avoid that designation. Being at the front desk means that you miss most, if not all, of what happens during the festival. She’s right. I miss out on all the interesting panels, but catch pieces of conversations as people move from one panel session to another. There are five other people with me including Ona, Yétúndé and Stephanie.

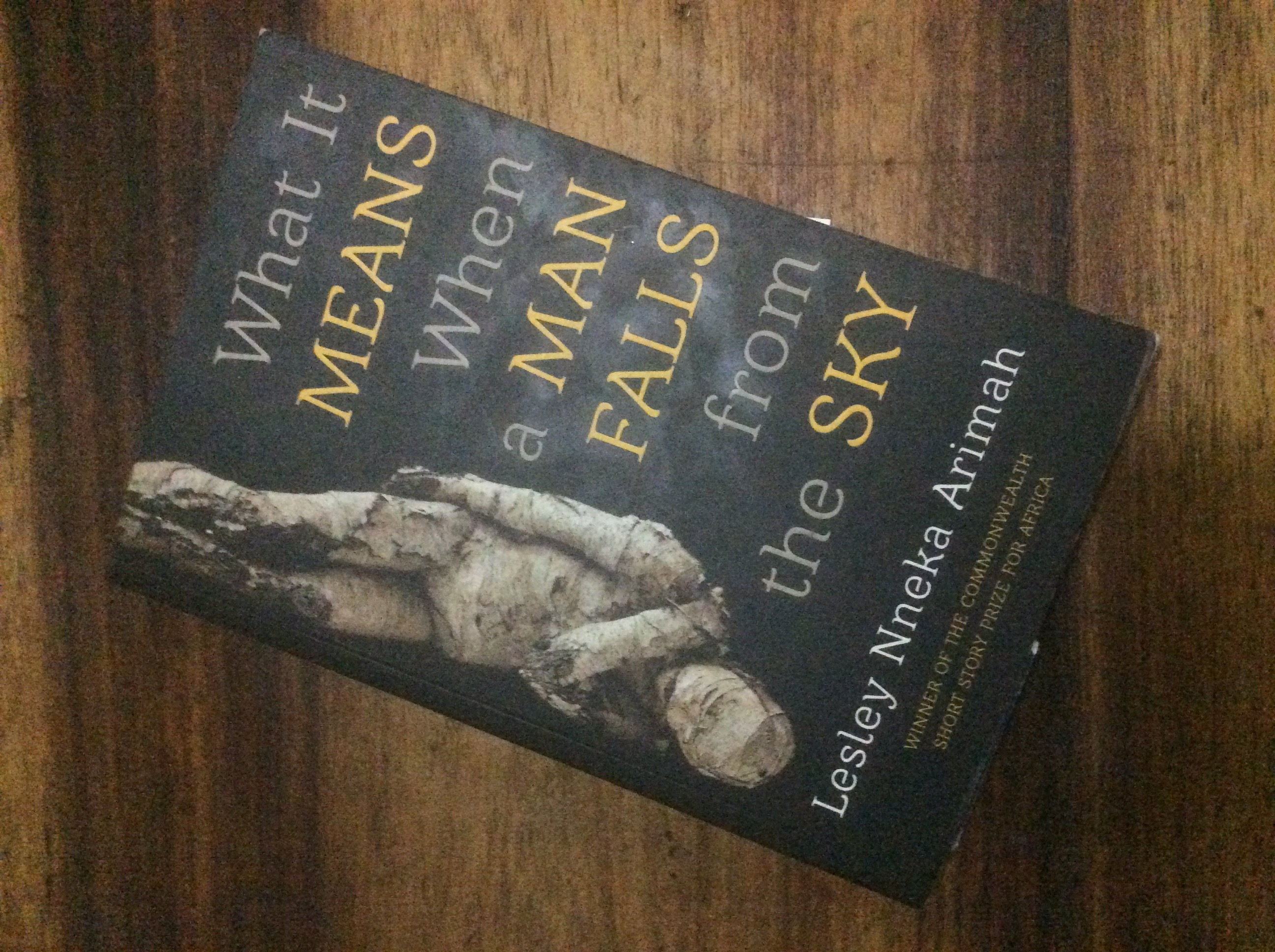

We start with sorting bags and tags for guests, visitors, press, and crew. There’s some downtime, during which I read my copy of What It Means When A Man Falls From The Sky by Leslie Nneka Arimah. There’s more sorting, packing, getting to know each other, setting up, tweeting, chatting, and reading. Somewhere in the middle of all this, there’s a call. I have to leave for Lagos very early the next day. I inform Ify of this development.

We start with sorting bags and tags for guests, visitors, press, and crew. There’s some downtime, during which I read my copy of What It Means When A Man Falls From The Sky by Leslie Nneka Arimah. There’s more sorting, packing, getting to know each other, setting up, tweeting, chatting, and reading. Somewhere in the middle of all this, there’s a call. I have to leave for Lagos very early the next day. I inform Ify of this development.

I leave for Lagos at 7pm AM, my business takes longer to sort than I expected, so I get back to Abeokuta at about 5pm. I’m told that I haven’t missed much, and registration starts shortly after I arrive. I work out a system to get through registration quickly. We register guests and attendees till around 9pm.

From Wednesday till Saturday, I spend all my time at the registration desk, except for when I go for food breaks or toilet breaks. This is where I get Mona Eltahawy to sign my copy of Headscarves and Hymens. This is where I get to meet Bim Adéwùmí, who is one of the major reasons I decided to attend the festival. This is where I finally put faces to names and Twitter handles. This is where I develop an addiction to kòkòrò. This is where I catch up with people I never see, except at these things. This is where I find out about and enter the Aké Festival giveaway, which I will come to later. Being at the registration desk means that I meet almost everybody who came for the festival. It also means I have to smile a lot, even when I’m tired and hungry, and when I’m upset because almost everybody else who’s supposed to be helping at the registration desk is not.

One of the highlights of my time at Abẹ́òkuta isn’t at the festival, but in a small hotel room party a few minutes away from the hotel where volunteers are lodged. Another highlight is the Palmwine and Poetry night. I caught the tail end of the event, as we closed the registration desk at about that time. I came in in the middle of Poetra’s relatable poem on feminism, and I also heard Koleka Putuma perform a few poems. The brightest highlight is winning the book grant.

At the end of the event, Lọlá Shónẹ́yìn gives a thank you speech, after which I am announced as the winner of the Aké Festival book grant. I have won N25,000 to buy books at the festival bookshop. The night, and the festival, ends with a party.

The next day, we go back to the Cultural Centre to pack up the bookshop, I redeem my books, and combined with books received as late birthday gifts, I leave Aké with 16 nooks, and the stipend volunteers receive at the end of the festival.

Aké is always a delight.

Even if you’re stuck behind a registration desk for all 4 nights and 3 days of the festival, and have to make do with a barely good DJ (last year’s DJ was great) at the closing party you’d been looking forward to since Day 1. Being surrounded by friends and people you admire, Africa’s best writers, upcoming writers, book lovers, and art aficionados, and managing to listen in on concerts and performances happening close to the front desk make up for it.

Literary festivals are delightful because they are a few days of mingling with people, who for the most part, enjoy the things you enjoy. I have attended Aké as a [one day] visitor, now, a volunteer, and, next year, a full event visitor, or maybe a guest (a girl can dream).

______

Déàdúràmiládé Tawak is a reader, writer, and researcher. She was the second runner-up in the CREETIQ Critic Challenge 2017, and has had her flash fiction, essays, interviews, and reviews published in Brittle Paper, Athena Talks, Africa in Dialogue, and Arts and Africa. She lives in Lagos and tweets from @deaduramilade.

One Comment to Aké Festival (2017): A Volunteer’s Recap so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)