Guest post by Ernest Ògúnyẹmí

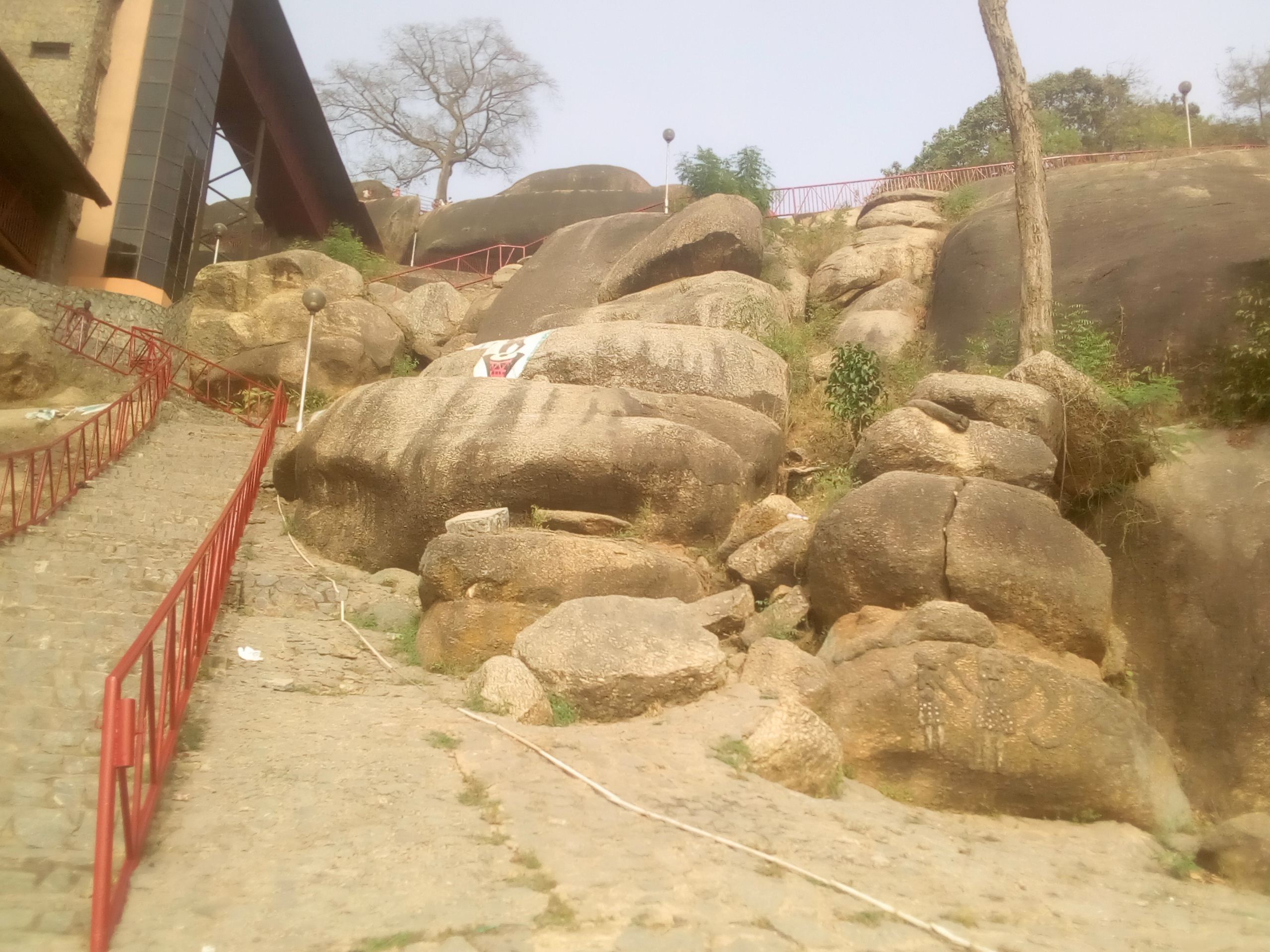

After buying a one-thousand-naira ticket, which I’ll later learn was just to climb the rock, a man walks up to me. He wears a face that looks tense, like cold pap, half-covered in unshaven beard, and is dressed in this Ankara that looks over-washed, and schoolboy sandals.

‘We’—he uses the pronoun that only the God of the Quran uses—‘are the ones that will guide you and tell you the history of this place.’ I’m thinking of some men in Northern Africa who are said to be the custodians of the people’s history. Is this man something like that? Custodian of the history of Olúmo? He brings me back with his voice, harsh but soft-coated. ‘Our own money is just three thousand.’

I watch the way the word just makes it out of his lips: like water making itself out of a tap, hitting the ground. Just. Wait. Is it because I am wearing a white long sleeve shirt that has Noir written on its back in a mad design? Is it because I’m asking why there is a pot of water decorated with cowries here when Abéòkuta is so far from Òsogbo? Is it because I’m taking all these photos? What is the man thinking sef?

I don’t let the words go cold before I launch mine like a missile. ‘I don’t have three-thousand-naira o.’

He says nothing. He tells me to come, ‘Let me show you the Art Gallery.’

The Art Gallery is one of three buildings that look like Agbolé, a compound of houses, the only difference

I go on taking photos, even as my guide (that’s what I call him now; we already had an agreement. Didn’t we?) tells me, ‘The man that stays here does not allow people to take pictures of the artworks. But since he is not here, go ahead. Do quick.’ As I take the pictures, he tells me: ‘Where you are standing used to be Agbolé. People used to live here.’ And I’m like: Damn it. I was right.

I walk past ‘The man that stays here,’ who is looking into the air, past the walls of the gallery, into something deep, something that might become another gorgeous painting, or woodwork, or bronzework. Or whatever. I walk to the calabash of beads, pick one and ask him for its price.

‘Hundred naira,’ he says.

I pick another one. He says it is five hundred naira. I decide to buy this one, not because I can’t check for better ones, but because I’m already feeling like I am disturbing the flow of inspiration falling upon ‘The man that stays here.’ He takes one hanging from a nail in a flat surface and wears it on my wrist. I hand him a five-hundred-naira note. He pats my back and says ‘Thank you.’

As we walk out of the Art Gallery, a mother and her children and a man (another guide) walk in. We walk through a narrow way between another Art Gallery and a building till we get out to a path that leads one way to the flight of 12o stairs that will later bring us to what my guide calls ‘The first stage’, and one way to I-don’t-know-where. There are a number of trees, under which there are concrete seats. Under one of the trees, on one of the seats, a lady is telling a guy she wants to bite him peacefully, but the guy says never. ‘Ahah. How can you bite a person in peace? You can only bite me when we are quarrelling, not in peace,’ the guy says. ‘Or, brother,’ referring to me, ‘what do you think?’

I smile and take a picture of them. I don’t say what I think because I’m thinking dirty things.

After we climb the 120 steps that lead to the first stage of Olúmo, we

‘This is the Pansẹ́kẹ́ Garden, named after the pansẹ́kẹ́ tree,’ he points at a tree. I think of Pansẹ́kẹ́ bridge, the too long pedestal bridge in Abéòkuta. I think of the man who sells secondhand books in front of Union Bank, behind Catholic Comprehensive. Was there a pansẹ́kẹ́ tree there, too? Is it why they call that place pansẹ́kẹ́? Maybe. My guide goes on: ‘The English people call it “flamboyant tree”. People sit here to catch their breaths and enjoy themselves.’

‘How about these other trees?’ I point to two trees.

‘That is the ọdán tree—the English call it ‘doggedness and resilience tree’—and that is the

I shake my head as I think of how to put ‘neem’ down on paper. After a while I settle for ‘neam’, I’ll make the correction with Google.

*

Now we are before a door that enters a cave in the rock. The door is covered with feathers, mostly white and some brown, and on the lefthand side of the door there are used bottles of Schnapps.

‘This is the shrine,’ my guide says, ‘it is here they make sacrifice to the rock. People also come here to ask for whatever they want, and when they get it they return to give thanks to Olúmo. That is why you are seeing all these feathers.’ He adds that the sacrifice-things are: a black cow, ‘pidgin’ kola, and Schnapps.

‘Pigeon kolanut,’ I seek clarification.

‘Pidgin,’ he says. ‘Those birds that fly.’

OK. I get it. The man is Ibo. Or does he just sound Ibo-ish? What does it matter if an Ibo man is a custodian of the history of Olúmo, the most fascinating site in Abeokuta history, and, indeed, one of the most fascinating in Yorùbá history?

I joke about why it is a black cow that is used for the sacrifice and not a black goat, and my guide replies: ‘That is what Ifá said.’ Ifá, the Oracle,

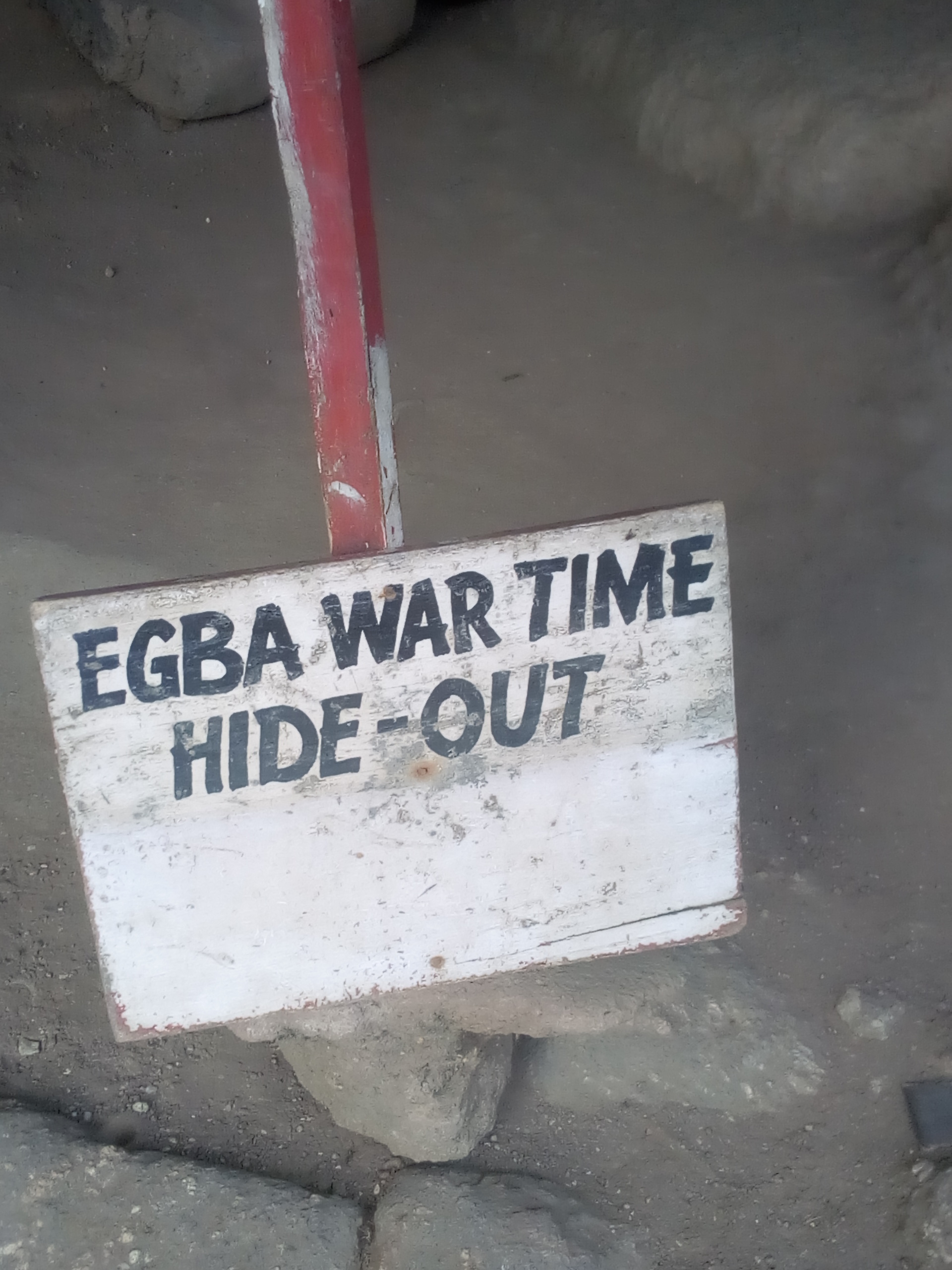

My guide leads me to a side of the rock that has a small signboard that reads: WARTIME HIDE-OUT, printed in black on a white surface, resting on a red pole. I’m not sure they had this in mind when they put that signboard there, but I’m thinking of each colour as message: war on peace, against a backdrop of blood.

‘This was where the warriors hid themselves during wartime.’ It is a cave that has a door, or something that looks like a door—

I walk out of the rock. My guide points to a grave where a chief was buried and talks about the chief being Òsi-Oba in his days. But I’m not really with him. I’m somewhere else in my mind. The images of warriors climbing up here, crawling into this place for safety, making home here pops up in my mind. I can see women, on their knees singing, their hands working stones into these holes to give their men fine soup, their bodies moving in rhythm, even as the roar of their enemies came from

*

I am standing before some women who have identical Ankara wrappers around their bodies, sitting on a mat, outside a building with paintings of sacrifice-things and idols. On my right is a shrine, the òrìsà Ọbalúayé shrine, a concrete mole having an opening where they pour squashed palm-fruit and oil. A voice that sounds like

‘Àyìnlá,’ he says, unsure. ‘Àbí, who is it?’ he asks the women. ‘Shebí that is Àyìnlá’s voice.’

‘Does this sound like Àyìnlá to you?’ a woman asks.

He says he is not so sure and then joke around with words, until they tell him it is Kollington.

While they talk, there is this smallish woman who just smiles and listens. She has royal beads around her wrist, and some others, not royal, around her neck. My guide tells me she is Ìya-Olúmọ, the Priestess of the rock. ‘She was born in 1884 and she is 134 years,’ he says. ‘Give them whatever you want to give them and let’s go.’ I put my hand in my pocket and give Ìyá-Olúmọ something light.

*

We negotiate a bend before getting to the other side of the rock, where there is a sculpture of the head of Lísàbí, Agbòngbò Àkàlà, the first Balógun of Ẹ̀gbá, and

Here there are all these fine people playing

Now my guide is poking my inside with his words, making me feel like a sinner, he forming God.

‘I told you I told I don’t have three thousand.’

‘But you would have told me the amount you have, not make me come from that place to this place for nothing now.’

‘But I told you I don’t have three thousand naira.’

He sits back. ‘OK. It is my fault.’

‘No,’ I say. ‘We are both to blame.’

There is silence on both ends. A man selling

I tell my guide I have just five-hundred naira, and he swears he’ll never walk up here and tell all those stories for five-hundred naira. He puts his hand in his pocket and shows me some money. ‘A man paid me this one,’ he shows me three-thousand naira, ‘and this one,’ two-thousand naira, ‘another man gave me.’ He says something about me being wicked, or being in rank with wicked men. I ask if he is not paid by Olúmo, as one of its staffs, and he tells me: ‘I, and the others, you know we are plenty, pay to work here.’ And he walks away, spends some time chatting with a deaf guy, and then comes back to say, ‘Bring it.’

I tell him I have one-thousand naira.

He sticks his hand in his pocket and brings out two five hundred naira notes. He hands me one as I give the one-thousand naira note. And he walks away.

For a long

Suddenly, some girls walk up to me and ask what I am doing. The most beautiful among them talks about my writing not being legible. As she walks away, she says I’m most likely writing a project; either that or, I’m one of those guys doing Theatre Arts. A friend of hers says: ‘It is you that will know.’ The lady smiles and says ‘Life has become thin-skinned.’

As I walk down the flight of stairs, the alternative to the ancient way, I hear the harsh voice of my guide who calls me wicked, and the magical voice of that babe who talked about life being thin-skinned. And I smile.

_____________

Ernest O. Ogunyemi is an eighteen-year-old writer from Nigeria. His stories and poems have appeared in Acumen, Litro, Agbowó, The Rising Phoenix, and many more. He is a product of the recent WriteWithStyle Workshop, and a participant in the Goethe-Institute Afro Young Adult workshop. He dreams of writing: a novel, a story collection, and a collection of essays on love and home and loss.

No Comments to My Guide Up the Rock so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)

No one has commented so far, be the first one to comment!