I spent a few hours last week in the house of an American colleague, Tom Lavallee, who teaches Chinese here. He had invited me and a few other friends for an evening of Chinese food and conversations in his St. Louis home. His partner is a Chinese woman who works as a writer as well as a translator from Chinese into English.

The conversation soon turned to the matter of writing, and the challenge of translating from one language to the other. What is lost in translation? What remains? How authentic is that product of translation in representing the original thought of the writer? Who makes the call of how translations should turn out? How much is taking too much liberties with original ideas? Where does translation end and improvisation/adaptation begin? They were interesting questions for me not only because I’d considered them many times myself before, but also because I discovered, a few years ago, that the translation of George Orwell’s classic book Animal Farm into German was not uniform because the translators belonged to different ideological camps during the cold war. I have spent countless moments pondering the literary tricks that would be needed to render something so clearly anti-socialism (or at least anti-leninism) as anti-capitalism. But then, that is the power of translation – which thrives on running an original idea through the conduit of the mind of a removed second reader-writer.

The conversation soon turned to the matter of writing, and the challenge of translating from one language to the other. What is lost in translation? What remains? How authentic is that product of translation in representing the original thought of the writer? Who makes the call of how translations should turn out? How much is taking too much liberties with original ideas? Where does translation end and improvisation/adaptation begin? They were interesting questions for me not only because I’d considered them many times myself before, but also because I discovered, a few years ago, that the translation of George Orwell’s classic book Animal Farm into German was not uniform because the translators belonged to different ideological camps during the cold war. I have spent countless moments pondering the literary tricks that would be needed to render something so clearly anti-socialism (or at least anti-leninism) as anti-capitalism. But then, that is the power of translation – which thrives on running an original idea through the conduit of the mind of a removed second reader-writer.

I’ve read a few Chinese literature in English. We discussed the ideas behind Soul Mountain, the famous novel by Gao Xingjian, translated by Mabel Lee into English. It is a travelogue of some sort incorporating elements of soul-searching autobiographical non-fiction, fiction, vignettes, ethnographic writings, musings, jottings, poetry, and story fragments. One of the challenge of translating from Chinese must also include rendering an idea of communality into an English-speaking culture of individualism. But therein lies the pleasures of translation – a special brand of serving that is not totally belonging to one culture, and not totally transformed into the other. In language learning, that would be a sort of “interlanguage” – a language that is neither the first nor the second language. What we read when we read something translated into English from Greek or Latin, or Arabic, is neither those languages, nor is it English. The ideas are most times successfully conveyed in the target language, but not enough to prevent literary/language purists from a snobbery that insists on the original as the most authentic standard bearer. And they are sometimes right. Yet, the “interlanguage” of translation carries in itself an original and yes authentic voice.

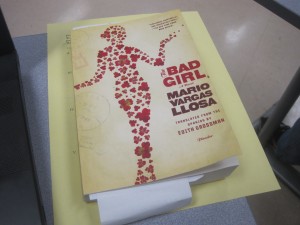

Garcia Marquez is famous in English speaking Africa even though we don’t speak Spanish. Vargas Llosa will be too soon enough, for good reason. How much did we lose if we did at all reading in English? Does it ever matter? Does my friend from Morocco have a better and richer literary experience than me because he speaks Tamazight (his local language), Arabic (his national language), and French (his country’s official language) and English and is thus able to read many more literature in original languages? If I read Naipaul in English and he reads it in French, what have I gained that he hasn’t? Does an Indian reading Naipaul or Rushdie (in English) gain something more? After all, they are co-sharers in the cultural conditioning that produced the texts? If I read Onitsha by JMG Le Clezio in French, do I gain any more or less than those who do it in English? After all, the writer is French. But then, after all, I am Nigerian, and the story in the book are based on the writer’s adventures in the Nigeria of the 60s. For those who have read George Orwell’s 1984 in German, or in Japanese, how does the writer translate words like “newspeak” and “thoughtcrime”. Does it make the same compact sense as it does it in English?

Garcia Marquez is famous in English speaking Africa even though we don’t speak Spanish. Vargas Llosa will be too soon enough, for good reason. How much did we lose if we did at all reading in English? Does it ever matter? Does my friend from Morocco have a better and richer literary experience than me because he speaks Tamazight (his local language), Arabic (his national language), and French (his country’s official language) and English and is thus able to read many more literature in original languages? If I read Naipaul in English and he reads it in French, what have I gained that he hasn’t? Does an Indian reading Naipaul or Rushdie (in English) gain something more? After all, they are co-sharers in the cultural conditioning that produced the texts? If I read Onitsha by JMG Le Clezio in French, do I gain any more or less than those who do it in English? After all, the writer is French. But then, after all, I am Nigerian, and the story in the book are based on the writer’s adventures in the Nigeria of the 60s. For those who have read George Orwell’s 1984 in German, or in Japanese, how does the writer translate words like “newspeak” and “thoughtcrime”. Does it make the same compact sense as it does it in English?

I first read Plato On the Trial and Death of Socrates in the early 2000s and what struck me the most was how beautifully it was written. It was a translation. Plato did not write in English. A few of the other plays we read as undergrads The Frogs by Aristophanes, Oedipus Rex by Sophocles, and Wole Soyinka’s notable translation of D.O. Fagunwa’s classic novel into The Forest of a Thousand Daemons all struck me as bearing very distinct literary styles that stand in their own stead as authentic study of thoughts in translation. The last time I read Plato On the Trial and Death of Socrates was late last year in Edwardsville, and I was greatly surprised at how insipid it read compared to the one I read back in Ibadan. The conversation on the dinner table went back and forth within these many areas of literary translation and I learnt as much as I grubbed. By the time the evening was over, all I wanted was a financial grant to go live in a small house by river and complete all the pending translations I have been working on for many years.

The last time we conversed, I sent them a long Yoruba to English translation of some of my father’s poetry. Half insecure in my experimentations (I’d completed the translation in 2005 and haven’t worked on it since then), and half wondering if any of the beauty of oral literature is lost when they become text, I was pleasantly surprised to read as a response to it, an email from my colleague: “That is a lovely, rich and absorbing poem,” it read “I have read it twice and found myself drawn in so many directions, wishing I could climb its hills, listen to its music more closely and roll around in its musky earth – love is a vast world, mysterious and ordinary and always full of pungent flavors and astonishing depths and heights. I would like to read more.” See? Maybe all that is lost to translation should be the expectations we bring to it from our knowledge of the depths of the original. A few hours later, he sent me a work-in-progress Chinese to English novel translation excerpt that he and his partner (the writer) had been working on. I found it a delightfully splendid read. And I don’t speak Chinese.

Good literature will always speak out, in whatever tongues it finds.

No Comments to Discoursing Translations so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)

No one has commented so far, be the first one to comment!