by Tope Salaudeen-Adegoke

“Travel is a vanishing act, a solitary trip down a pinched line of geography to oblivion.”

– Paul Theroux

The excitement won’t let you sleep, I mean, when you want to travel a long distance you’ve never travelled before. So I woke up very early, unusual of me—I am a late sleeper, that morning, to link up with Servio at Benue Links’ Park, opposite the University of Ibadan’s main gate. Could it even be called a park? It’s right beside the Mobil filling station. Their office is a tiny cubicle behind a warehouse that is also used as a workshop by a roadside vulcaniser. This vulcaniser also doubles as an agent of some sort for the transport company. He helps in unloading luggage.

The excitement won’t let you sleep, I mean, when you want to travel a long distance you’ve never travelled before. So I woke up very early, unusual of me—I am a late sleeper, that morning, to link up with Servio at Benue Links’ Park, opposite the University of Ibadan’s main gate. Could it even be called a park? It’s right beside the Mobil filling station. Their office is a tiny cubicle behind a warehouse that is also used as a workshop by a roadside vulcaniser. This vulcaniser also doubles as an agent of some sort for the transport company. He helps in unloading luggage.

The two Toyota Hiace buses, commonly known as the Hummer Bus in Nigeria, are painted white with two dark green horizontal stripes at the middle of the vehicles. At the base of the lines, “Benue Links” is painted. They were parked in front of the place. A conductor called our tickets. I was with number four and Servio number five. He directed us to the bus in the front. I had hoped we would be called into the second bus because it was neater and had an automatic gear. I would later understand the reason why the first bus was rough and dirty.

When it comes to efficiency in transport services in Nigeria, just forget it. And never be in a hurry. They could be a pain behind the wheels at times, which is the very reason we had planned to travel earlier so that we could arrive at Makurdi a day before the commencement of the programme we were going for. After their usual delay, sorting passengers’ luggage under the seats, on the back seats haphazardly, in the trunk—it was a little space because another passenger seat had been wedged onto the little space— spilling to the seat next to it which irked some passengers as they were shoved and made uncomfortable even before we set on the journey, some other passengers entered. It was a reckless combination of people and luggage.

A woman came to the entrance window praying for journey mercies. I was responding “amen” under my breath when squabbling erupted from the back. A passenger and the conductor were arguing over mishandling of her luggage. The praying woman intervened and a compromise was reached. The driver hopped in. He was a rather dirty looking man. He wore a dirty shirt and three-quarter pants. The only thing that impressed me about him was his neatly shaped hair and moustache. His hair, sprinkled with brilliant greyness is the only neat feature belonging to his seemingly nonchalant dress mode. The remaining passengers filed in and took their seats on the three rows behind us. She continued the prayer and by that time I had already lost interest. At the end of the prayer, she was tipped by some passengers. She received it with “God bless you” and the recipients variously salted it with “amen”.

The driver turned on the ignition and pulled up on the road. We zig-zagged out of the city to the expressway of Ọ̀jọ́ọ̀, then to Iwo Road; the time was probably a few minutes to eight.

“Won’t you sleep for a minute?” Servio asked. The question was directed at my red eyes rather than me.

“No. Curiosity won’t let me”. I smiled back.

He feigned a smile and curdled his face on his lap to take a nap. We were speeding along the highway when a man, seated beside the driver, called the attention of the driver to the door of the vehicle; it seemed broken on its hinge and did not close firmly. He parked to examine that and confirmed it was only a kind of rubber missing. He closed the door and joined the road again. Because the landscape was familiar to me, I decided to read a little. I had with me a Kindle from the Kofi Awonoor Memorial Library. I switched it on to return to the books I had been reading. I tried Daniel Dafoe’s The History of the Devil/ As Well Ancient as Modern in Two Parts. It was no good. I tried Satan’s Diary by Leonid Andreyev’s—same thing. The Confessions of St. Augustine Bishop of Hippo—I was not receptive at all; I was torn between the pages. I kept repeating sentences and peregrinating paragraphs. So I put it aside— I did not pick it up again throughout the journey. I returned to looking at the landscape wheezing past us: people, houses, filling stations, etc.

Travelling is a leisurely activity in the Global North with a considerable bit of risk, if at all. It is a daunting, and risky business in Africa. In fact, travelling for fun in some regions in Africa is suicidal. You have many factors to consider— the roads for example. Some have wondered and enquired about the way to hell. In simple truth, it is those potholes on Nigerian highways, which have led many away to their death. Oil tankers ferrying petrol to different parts of the country are noteworthy contributors, too. Carcass of cars like wrinkled cast away rags by the roadside are one of the things that will likely catch your attention if you are travelling on a Nigerian highway. I wonder if it’s supposed to be a reminder of death to travellers or some memento mori to reckless drivers. I can safely count these carcasses I have seen so far on this trip. It’s depressing. At times I imagine the ghost of accident victims perpetually present in the remains of the wreckage wriggling through the windows or driving the cars on the spot.

We had been in Ọ̀sun state, zipping through towns designated with local government signposts. The boundary between Ọ̀sun and Oyo States is a short drive from Iwó road of about 15 minutes. Ibadan is spreading more than ever. People are now building homes along various outskirts of the city. It was a short drive through Ọ̀sun. We took a left turn when we reached Odùduwà University facing the road connects Ifẹ̀ to Ondo State.

Ondo is a strange beast. In one nostril she is sniffing dust, in the other tobacco. Large billboards at various newly completed buildings scream the achievements of the Governor: ultra-modern hospital, modern primary school, newly tarred roads, blah blah. I felt like I was sneaking through the backyard of my neighbours to play with a friend on the next street. The comfort and sense of security that I was still in a Yorùbá speaking place betrayed my wanderlust. I felt like I was rooted on a spot. Modernity is seeping through the veins of the city of Àkúré. But the rusticity of their Yorùbá is still present in their tongues. The dialect is both fascinating and laughable, just like the core Ibadan accent, that I happen to speak, or old Ọ̀yọ́ accent. If you don’t put down your ears, you may not understand them when speaking.

There are lots of mountains in Ondo state. And for a moment, it seemed our bus flying on the road was like a futile effort of trying to cup water in a palm hoping not a single drop will escape. The driver’s devil-may-care speed was useless. It was as if he was trying to run away from that place. That gave me time to examine the mountains. The sun was already high so it made them clearer from a distance. I was looking at them and the word “black ass” kept tugging at my mind. They were black and hairy with arboreal growth. The thick blackness of the sedimentary rock was puzzling to me. I mentioned my fascination to Servio. He’s very good at providing details. He shared his NYSC experience, he served in Niger state, that there is a particular tribe that lives up mountain in the North, suffusing me with much more I anticipated for. It was almost useless, actually.

There’s a popular restaurant in Àkúrẹ́ that serves as stop over for inter-state buses. We had a stop-over there. Everybody was glad for the few minutes’ break to stretch their legs and empty their bladder. I walked down a road to take a leak. Servio had disappeared into the restaurant looking for a toilet to do his business. He bought a bunch of bananas and a bottle of Eva table water which he later regretted— more than half of the bunch turned out spoilt. Some of the other passengers bought refreshments as well. I love plantain chips, most especially when it’s sparsely salted. I had bought two packs from one of the roadside hawkers on the outskirts of Ọ̀sun, intending to give Servio one.

We slipped through Edo, rather briefly. We passed Akoko-Edo, Magongo, and small towns before we entered Kogi. The mountains there are very hairy. They are like hairy old men. Unlike the youthful blackness of the ones in Ondo, they are like fathers to children in their fifties.

I saw for the first time the Àjàokuta steel company. Labouring through a region where there were only huts— and the huts were poor, no more than mud shelter with grass roofs— and an occasional herd of cattle followed by young boys, we entered Benue. We came upon the bridge overriding the vastness of the Niger.

“A tributary!” Servio beamed. It was a pointer to the Niger River.

“In stagnancy!” I enthused.

I was responding to the wit in his remark. It was about a verse in his poetry collection, A Tributary in Servitude. That was when I decided to write this travelogue. And immediately I told him that, the conversations died down. He was careful of how he would be presented. Servio can be clumsily clammy at times. And his informed paranoia makes him extremely cautious with everything. I wouldn’t care though.

Dusk was approaching now, and I was excited that finally we are in Benue state. Two women alighted on the outskirts of the town. I was pretty disappointed with the dusty town of Otukpo, where the former Senate President hails from. It was rather too primitive except for the big Catholic churches.

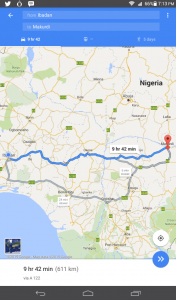

It was already dark, around 10pm by the time we arrived Makurdi. Having endured a hideous trip of about 10 hours covering about 613 kilometres in a cramped seat, it’s a wonderful feeling when we arrived at the Benue Links Bus Station. (In fact, it had the ambience of an airport because of the taxi drivers parked outside park soliciting to be hired). I was tired and bus lagged and I couldn’t be happier to get out of the bus. Our host, Su’eddie, came to welcome us.

_________

The Favourite Son of Africa is the pseudonym of Tọ́pẹ́ Salaudeen-Adégòkè. He is an editor, literary critic and poet from Ibadan, Nigeria. A member of WriteHouse Collective, Tope assesses manuscripts for publication and is one of the organisers of Artmosphere, a leading monthly literary event in Ibadan. He also works as the administrator of the Kofi Awoonor Memorial Library in Ibadan. He enjoys travelling and cooking.

No Comments to Overland From Ibadan to Makurdi so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)

No one has commented so far, be the first one to comment!