When I was in Kenya in 2005, I remember that one of the most recurrent observations I received from Kenyans was that Nigeria is a place filled with people who believe in witchcraft and practice it in their daily lives. We all believed in juju, they said, and none of the women I spoke to would dare to marry a Yoruba person for fear of one day having to deal with a mother-in-law that could turn them into a piece of metal at the slightest provocation. I have since discovered that this is a very prevalent perception of Nigeria, mostly obtained through our home videos that have been ranked third in the world in terms of output. Is there practice of witchcraft and a prevalent belief in it in Yoruba land today. The answer is yes. Does everyone believe in it. Erm, I would say yes to this as well, but with very few exceptions of the skeptics.

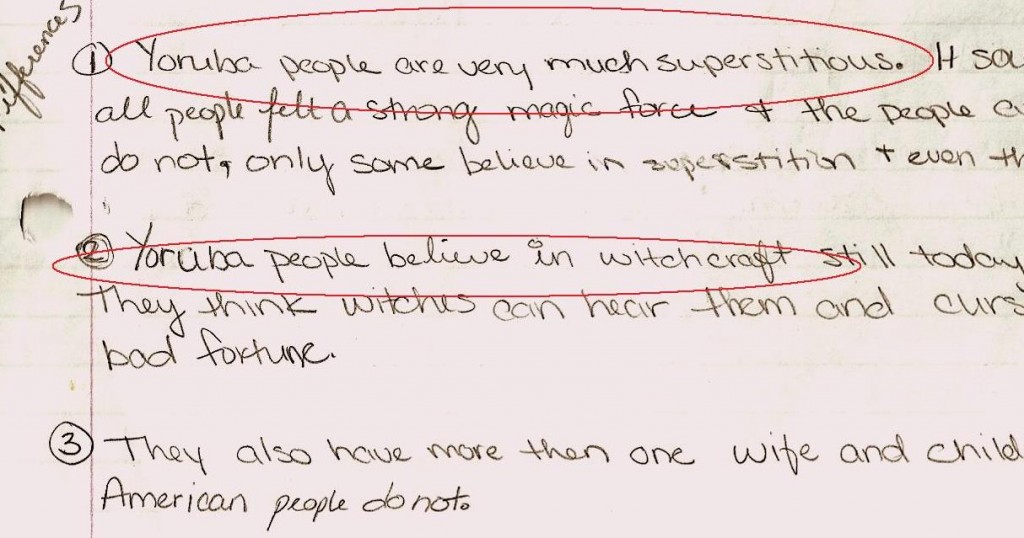

Cut to my fourth class, where I had asked my students to read a short story titled “Why Atide Is Taking To A Coin”, written by a German friend, student of Yoruba and a current PhD student at SOAS. I first read the short story in 2004 while it was still being written, and I got to contribute a few ideas to its storyline. So last week, when I asked my students to list ten things they found strange, new or memorable about the Yoruba culture from the story, and five things that they found similar to their own culture, I was trying to get them more interested in reading and discovering new things. It was also a way for me to get into their minds and see what they see when they look at me through the prism of Yoruba culture. The result amazed me. Of all the answers given to the first question, one was common to all the ten students in the class: They were surprised that a belief in witchcraft still exists/persists in some cultures of the world, particularly mine. They couldn’t understand why people ascribed occurences they couldn’t explain to the evil forces in their family, and they couldn’t understand why somebody who is Christian/Moslem would go to a Babalawo to get help with something that was bothering them.

Now, I could have easily said that it was the fault of the writer of the story for painting the Yoruba people in such a light, but when I look around Yorubaland today, I find not one but many leaders and public figures who would take their supporters or followers to shrines so as to get them to swear and take oaths of allegiance. Recently there was a case of a prominent state governor, and a lawmaker whose naked picture was taken at a shrine where he had gone to perform rituals. The fact is, belief in rituals are still as strong today in Yorubaland as it was before the British came. Whether this is a good or a bad thing is beyond my scope to say, but it took me some time of readjustment to deal with the truth, being a little lost to the effect such disclosures might have on the impressionable minds of my brilliant students, and their ability to see this somehow as a positive attribute of such a people with a complex culture and outlook on life.

Are we a modern society in Yorubaland, or are we still attached to the deep vestiges of the past? If the texts of our literature, the lines of our poems and the plots of our dramas are anything to go by, the answer might be far from what we always like to believe.

1

Bimbola at http://noneyet

I dont agree that the belief in the supernatural is still as strong as it was, pre colonisation. I think in some circles, it is still very strong but the belief is highly diffused due largely to modernity and other options. The average African mind is superstitious and they patronise Babalawos as much as they do pastors and Imams. One fine tomorrow, when we are a fully industrialised nation, we will learn to reason first before consulting God.

Then, the state governor episode can happen because people fear indigenous God more than the One in heaven. Dont blame them. The God in heaven does not have as much as histrionics as Ogun and co. He does not strike with fire like in the days of old. Naturally, any evil generation seeking a sign and cannot get from God will look for help elsewhere. I strongly believe that if we go into African Traditional religion full time, it wont take long before we lose faith in these gods. Why? Because, like the Christian and Muslim God, we will find that we have over emphasise their abilities. Constantly patroinising them will mean they will soon be demystified. Until we stop relying on the information we’ve heard from their worshippers and check them out by ourselves, we will still attach so much mystique to them.

Thanks

Posted at September 17, 2009 on 9:38am.