This is the concluding portion of a five-part report on the demolition of Ìlọ́jọ̀ Bar. The story began here.

_____________

One wonders how monuments are made in other places. Are they merely declared into existence or is active work usually done to make sure that the structures fulfil the physical role into which they have been designated? In the United States, when a building or structure is declared a “National Historic Landmark”, it is handed over to the National Park Service who then maintains it from then on, in perpetuity. About half of the historic landmarks in the US are still privately owned while under maintenance by the Park Service. In the case of Ilọ́jọ̀ Bar, one more thing that has boggled the mind is how – in spite of how high the stakes were for its survival – no one deemed it fit to insure it against accidental or deliberate demolition. Notwithstanding what has now happened, one wonders how things would have been different if either the Federal Government (through NCMM), the state government (through relevant ministries), the Brazilian consulate which had put premium on it over the years, and private stakeholders (Legacy Group, family members), etc, had taken out a joint insurance policy over the building to the cost of its current market value pending the determination of its fate.

Asked and Unanswered

Who applied for the demolition permit? Mr. Daniel Adébọ̀wálé didn’t say. How much was paid for the demolition itself? He didn’t know either. But approval was received from LASPPA. Why was that decision taken to pull down the structure? I asked my host. “We had to,” he said. “As a free citizen of this country, we have the right to buy, sell, or hold onto our property however we want. And as you can see in the documents yourself, we had pretty much no choice. They want to paint us as criminals and it’s unfair. We were afraid that the threats that Fáshọlá’s letter implied will come to pass if we didn’t do anything. But we couldn’t do it without permission. We applied to the appropriate authority, and got permission to proceed.” And why were the contravention notices not shown to the NCMM for immediate action? “We showed them all of these letters,” he said. “You want to know why the NCMM didn’t confront the state about these? You’ll have to ask them.”

The NCMM had, it turned out, written to LABCA after all. In a letter dated June 7, 2013 (seen here) and signed by Mrs. E.O. Ekuke (Curator), the agency intimates the state about the status of the building as a monument. It also informs LABCA that “there is an on-going high powered collaborative effort to carry out a full restoration of the building by… Lagos State Government, the NCMM, the Ọláìyá family, the Brazilian Embassy, and the Legacy 95 Group (as restoration architects).” It further states that the status quo be maintained and that “the building should not be demolished nor its prominent features altered as a national monument.” Since LABCA isn’t talking, I have sent an email to the director of NCMM, Mr. Yusuf Abdallah Usman, whose recent statement “ordered” the restoration of the demolished building. Did LABCA respond to this letter from his office? He or his office has not responded. I also wanted to know how much the Commission had spent on that building since it was acquired* in 1956. The statement put out however presented an indirect indictment on several government agencies involved. It seemed, in short, like finger pointing in four pages.

While I talked with him on Sunday, Mr. Daniel Adébọ̀wálé had started working with the family lawyer to put out a press release in order to counter the current negative narrative about his family. This has now been published in The Nation on September 28, 2016. He read a few lines to me in his house in which he defended the decision of the family and laid the blames squarely at the feet of all the government agencies concerned, particularly LABCA. And to prove the family’s long-term open line of communication with LABCA over the years, he also brought out two complimentary cards from officials of the Agency with whom he had been in contact on the matter over the years. “If they hadn’t talked to us, like they claim”, he said, “where did I get these from?” One was from an Engineer Kúnlé Làmídì (MNSE) and another from someone called “Bldr.” T.A. Adéoyè. (“Bldr” probably stands for “builder”). I asked Mr. Daniel Adébọ̀wálé why he thinks the Agency had so far denied any knowledge of the demolition or of any permit asking the family to “remove” the building. “I don’t know,” he said. You will have to ask them that too. “I will,” I replied. “I’ve tried.”

The Other Descendants

On the afternoon of Monday, September 26, 2016, in the office of the curator at the National Museum, Oníkan, I met with Mr. Eric Adéremí Awóbuyìdé. He is the third son of Deborah Ọláyẹmí Awóbuyìde (nee Ọláìyá), who was one of the original twenty-one surviving children of the Patriarch Ọmọlọ́nà. Deborah, who grew up at Ìlọ́jọ̀ Bar before leaving to marry into the Awóbuyìdé family, died in 1994, survived by seven children one of who was Eric. He was the third child. This makes him a cousin to Daniel Adébọ̀wálé and a nephew to Victor Abímbọ́lá. But they are not on speaking terms. Mr. Daniel, on Sunday, had said that Eric was the one who separated himself, along with his children, from the rest of the main family. To Eric, the Ọláìyá boys were the ones who had deliberately kept him out of the loop so they could benefit from the property alone. But he benefited himself too. He had an office in the property, which he was free to use as he saw fit. One of his daughters, according to Daniel Adébọ̀wálé, also operated a public toilet in the monument, which upset many members of the family.

Now at 73 years old, Eric Adérẹ̀mí stands at about five feet and nine inches, a sharp contrast to his Ìkòròdú cousin who stood at six-two. The mental acuity of both men struck me as being quite impressive in spite of health challenges they both faced in their advanced age. Daniel Adébọ̀wálé had acknowledged that symptoms of arthritis in his limbs kept him from going out much these days. His cousin, without having to say it, exhibited some form of hearing impairment that made me have to repeat questions a number of times before they were comprehended. We were meeting for the first time, yet they had both spoken to me like a long lost friend, openly and without preconditions.

Eric had an earnest tone of voice that suggested that he also wanted his side of the story widely told. He has some free time now, he said, having retired in 2004 as a Principal Registrar of the Lagos State High Court. His son, Ọláṣùpọ̀, who operated a lottery centre in the building before it was demolished, had spoken to me for my last report, and facilitated this connection. “My father knows everything,” he had said. “Ask him.” In Eric’s hand was a leather folder containing sheaves of documents he had brought for my sake. “This” referring to the folder, “is my office now,” he said, “Since they demolished the office I had at Ìlọ́jọ̀ Bar, I have had to carry this with me.”

Audible in the earnest firmness of his voice was a huge sense of loss at the fate of his grandfather’s house and their childhood home. He had created an office for himself in the building specifically to be able to keep an eye on the property. This, he said, had been helpful a number of times when the demolition would have taken place except for his timely intervention by confronting the invading developers and sometimes calling the police. He it was who first alerted the National Commission on Museums and Monuments of the existence of an existential threat to their grandfather’s property by some invading developers who he suspected had taken their orders from other members of his family too ashamed of their role to show their face at the demolition site. Mr. Daniel Adébọ̀wálé had acknowledged that on Sunday as well, disapprovingly. Eric’s role was also referenced in the statement by Yusuf Abdallah Usman, the Director General of the National Commission for Museums and Monuments, dated September 11, 2016.

Approvals and Reversals

As we spoke, Eric brought out a series of documents each looking almost as new as when they were printed. Some of them I had seen before at his cousin’s Ìkòròdú home, like the contravention notices and the Demolition Permit approval. Some I was seeing for the first time, like the reversal of the demolition permit issued earlier in the year. This I had not prepared for. There was a reversal of the Demolition Permit!? Yes! The letter, dated July 19, 2016 and signed by one “Tpl.” Badéjọ H.O., expressed “regret” for having approved the earlier permit that gave a go-ahead to the demolition request by the family. It acknowledged that the building was indeed a federally designated monument and blamed the confusion that caused the initial permit to be issued on not being informed by whoever had applied for the demolition permit that the building was indeed a monument. All emphasis mine!

A second letter came on August 30th, 2016, this time from the governor’s office, signed by Agboolá Dábírí (the Special Adviser on Central Business Districts) and Fọ́lọ́runshọ́ Fọlárìn-Coker (Commissioner for Tourism, Arts & Culture). The letter, originally addressed to the Special Adviser, Urban Development, Ministry of Physical Planning and Urban Development, requested that the Demolition Permit already in circulation, in the hands of the elders of the Ọláìyá family, be withdrawn. It also requested that “a public announcement” be made by the ministry “to the effect that the property is a national monument and is to be preserved as such.”

A third and most earnestly written letter was addressed to the newly-elected governor of the state, Mr. Akínwùnmí Ambọ̀dé. Signed by the same two state officials already mentioned above, and also dated August 30th, 2016, it detailed the status of the structure as a national monument, alerted him to the presence of a wrongly-given Demolition Permit already in circulation, and of the existence of “a portion of the Ọláìyá family… intent on redeveloping the property for commercial reasons”. The letter implored the governor to “consider the purchase of the property from the Ọláìyá family for overriding public interest”, immediately revoke the outstanding permit for demolition, and begin “maintenance works “to restore the property for conservation purposes.”

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/284924874″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

Eric, on getting the letters became slightly less worried, but not any less wary. Whoever would apply for a demolition permit under the name of his dead grandfather was up to no good, he thought. So he made copies of the new letters and the demolition permit reversal order, enlarged them, and pasted them all around the property to deter all intruders. To forestall a surprise attack, he also started arriving at his office at five-thirty in the morning and leaving as late as possible after surveying the area for signs of any demolition equipment. Nevertheless, during the last year, there were at least three near successful attempts to tear down the building. One of them occurred under the protection of military men of the Nigerian Armed Forces (photos below) and ended with one of the arches of the structure broken by the caterpillar’s hydraulic extractor arm. The attack was, still, successfully stalled by the help of the resident crowd and the Nigerian Police Area A Command Center at Lion Building nearby. But Eric Adérẹ̀mí Awóbuyìdé’s worry doubled. The distance to the police station on a day of clear traffic is about six minutes. But on most days when the Island was busy and full, it could take twenty minutes or more. Plenty could go wrong in that time. Still, he hoped that the new governor would heed the call of the letter, and relieve him of his worries. That never happened.

The conversation, over an hour long, went into many tangents many for which I already had corroboration. When we were done, I asked him what he would want now, going forward. What would he want to happen? He looked wistful. “I’m Awóbuyìdé”, he said. “The male children of Ọláìyá and their sons have decided how they want the family to be run, and it is unfortunate. I’ve told Victor Ọláìyá to back off. He is a trumpeter. What does a trumpeter know about law and real estate?” He seemed really peeved by what he thought was a betrayal by his famous uncle. “When my grandfather looks back at us, he would see that I tried my best to protect his property! I can’t say the same for his children,” he said, and continued: “What I would hope for is that whoever did this should be shamed and prosecuted. The governor is culpable. We have to prosecute him too. I blame him for everything. He knows something. He could have stopped this if he wanted to. He wanted this to happen. Please print this on the front pages, with a good picture of my grandfather’s house. I want Buhari to see it. I want the whole world to read about it.”

He continued, “I would also wish that nobody else be allowed to build anything else on that spot. Turning it into a public recreation park would be more acceptable to me than a stupid plaza,” he concluded.

The Last Days of Ilọ́jọ̀ Bar

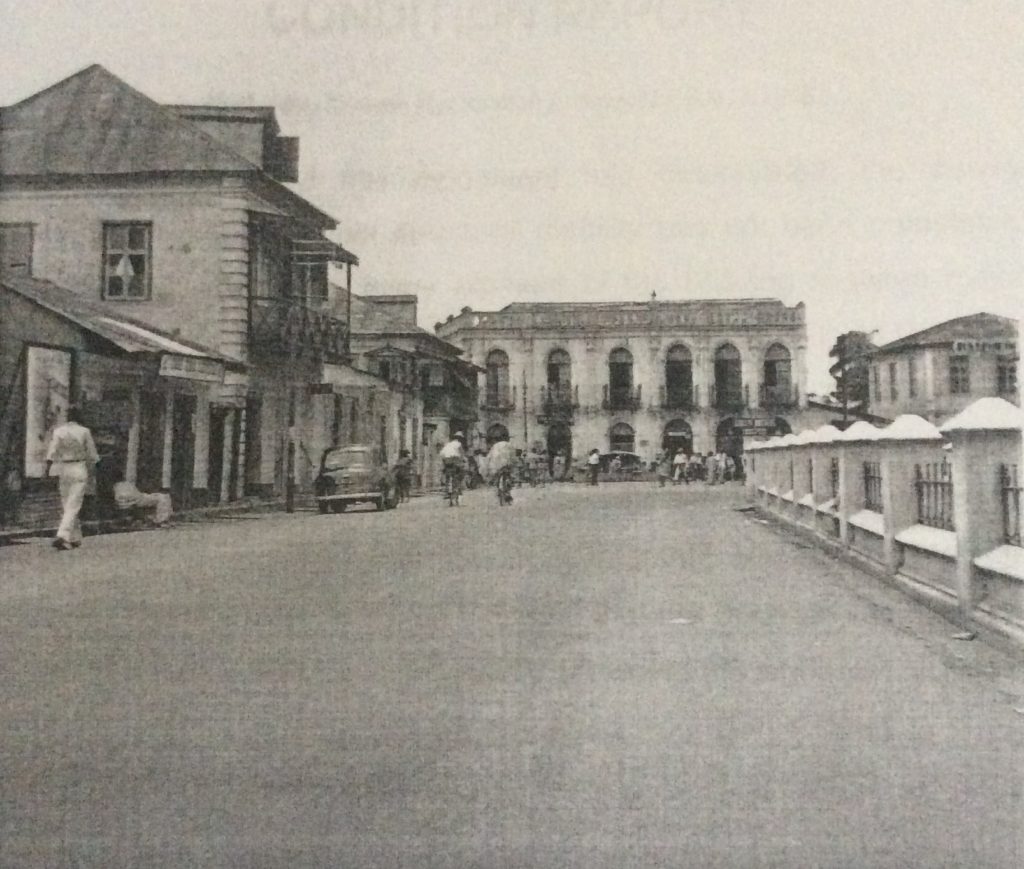

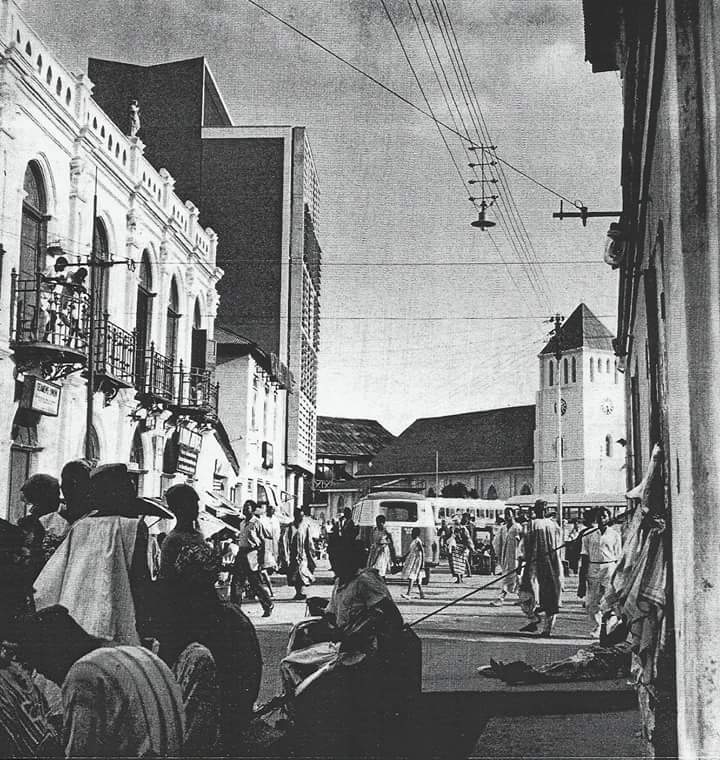

When the building, once known as Casa do Fernandez, was bought in 1933 by Alfred Ọmọlọ́nà Ọláìyá, it cost £2500. By 1956 when, as Ìlọ́jọ̀ Bar, it was “acquired”* by the Colonial Government as a national monument, it must have cost perhaps double that value. Three and a half weeks ago, while it still stood in its home spot, anything from 50 million (£122,695) to 200 million naira (£490,780) would have been needed just to restore the structure back to a decent habitable state, which is close enough to the current value of the piece of land of that size alone in Lagos Island.

At some point in the past when the conversations among the stakeholders (State Government, NCMM, Brazilian Embassy, Legacy Group, and the Ọláìyá Family) went well, a sum of thirty million naira (£73,346) of the targeted fundraising was proposed as payment to the Oláìyá family as a token for their gifting of the structure to a national/artistic/cultural purpose. That money was never raised, of course. The gala planned to facilitate the it never took place. Perhaps because of the transition from one state administration to another, perhaps because of a lack of interest in the value of history, perhaps because of a terrible misunderstanding between agents of government, perhaps because of an administration’s interest in the cosmetics of new real estate projects than the value of old ones, or perhaps because of an incompetence or malice that reaches to the high levels of our government, the story ends in a tragedy.

In real figures, a structure as this which marked the history of more than just an extended family of a rich businessman, but that of a city and a country, is invaluable. It had more than money could buy. By the end of Sunday, September 11th, 2016, a permanent scar was created, not just on the soil, but on the soul of a country, leaving a putrid trail of shame in the hands of more than just a handful of people and government agencies. An officer of the National Museum, on being alerted that the demolition was about to start that Sunday morning, began calling the police officers who had, on other occasions, come promptly and stopped the intruders before damage was done. On this day however they had other things to do unless material incentive was provided. “We asked them to come and at least stop the intruders first, and ask for money later, but we were not successful”, he told me, choosing to remain anonymous. “It was too late… and we don’t have the power to forcefully summon the police to our use – as much as that would have helped.”

A diesel-operated CAT 320 caterpillar with a hydraulic extractor arm had arrived at Number 2, Bámgbóṣe Street since the day dawned. That morning, as daylight began, while Lagos Island stayed calm, enjoying a well-deserved holiday, the menacing machine roared to life.

_______________

* It turns out that Ìlọ́jọ̀ Bar may not have been properly acquired as a monument either. According to Mr. Daniel Adérẹ̀mi Ọláìyá, the structure was “acquired” in mouth only, with no material compensation to the occupants nor a mutual agreement on resettlement options. This, he said, nullified such an acquisition by the British Colonial Administration, and subsequent civilian and military administrators of the country who had laid claim to the structure over the years.

When I inquired about this from the Legacy Group, who has now started an online petition to have the building built back to exact dimensions (they have the drawings, after all), the response was “Yes… [the family] should have been compensated outright, or with a share of profits made from the proposed tourism function of the building.” It would be helpful to get clarification from officials of the National Commission on Museums and Monuments about just what responsibility that agency had and how it fulfilled it over the years, to Ìlọ́jọ̀ Bar, its owners, the state government on whose land the property stood, and to the country at large.

Officials from LABCA or LASPPPA never did respond to any of my requests. Neither did I hear back from the director of NCMM.

Update: (October 4, 2016) In a call to me on October 4, the officials of LABCA/LASPPPA who I’d spoken with on my visit to the agency complained that I’d painted them in my writing as being “uncooperative” when, according to them, they had been sufficiently helpful by telling me to “hold on” while the issue was “being investigated”. I responded, as I do now, that public interest wasn’t been served by their obvious stonewalling. I do not hold them, these public relations officials, responsible for anything here other than failing to connect me with their bosses and failing to have official on-the-record responses. They were quite friendly and helpful otherwise, and I thank them for talking to me. But the record showed that their bosses who were clearly aware of the role of their agencies in the matter chose silence and obfuscation when a public statement would have helped.

Update: (October 19, 2016) The Commissioner for Culture and Tourism, Mr Fọ́lọ́runshọ́ Fọlárin-Coker has been removed from office. As at this moment, I don’t know if it has anything to do with the demolition of Ìlọ́jọ̀ Bar. However, when I requested an interview with him or an on-the-record statement on the demolition, Mr. Fọlárìn-Coker declined, saying “No point. It will offend the system.”

_______________

Postscript

By Mr. Daniel Adébọ̀wálé Ọláìyá (two tracks):

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/playlists/264143509″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

******

******

By Eric Adérẹ̀mí Awóbuyìdé:

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/284924868″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

******

******

Appreciation

I’m grateful to Ìbíwùnmí Ọláìyá and Ọláṣùpọ̀ Awóbuyìdé for facilitating the interview with their uncle and father respectively; to Mr. Daniel Adébọ̀wálé Ọláìyá and Mr. Eric Adérẹ̀mí Awóbuyìdé for entrusting me with their stories; to Abby Ògúnsànyà for connecting me to Ìbíwùnmí; to Jahman Aníkúlápó and Yẹmí Adésànyà for editing suggestions; to the Ọlọ́ládé Bámidélé and Àlàbí Williams/Abraham Ogbodo of Premium Times and The Guardian respectively for the syndication opportunity; to Oluwalóní for support and patience; and finally to all anonymous sources quoted on this report.

5 Comments to A Failure All Around so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)