By Kola Tubosun

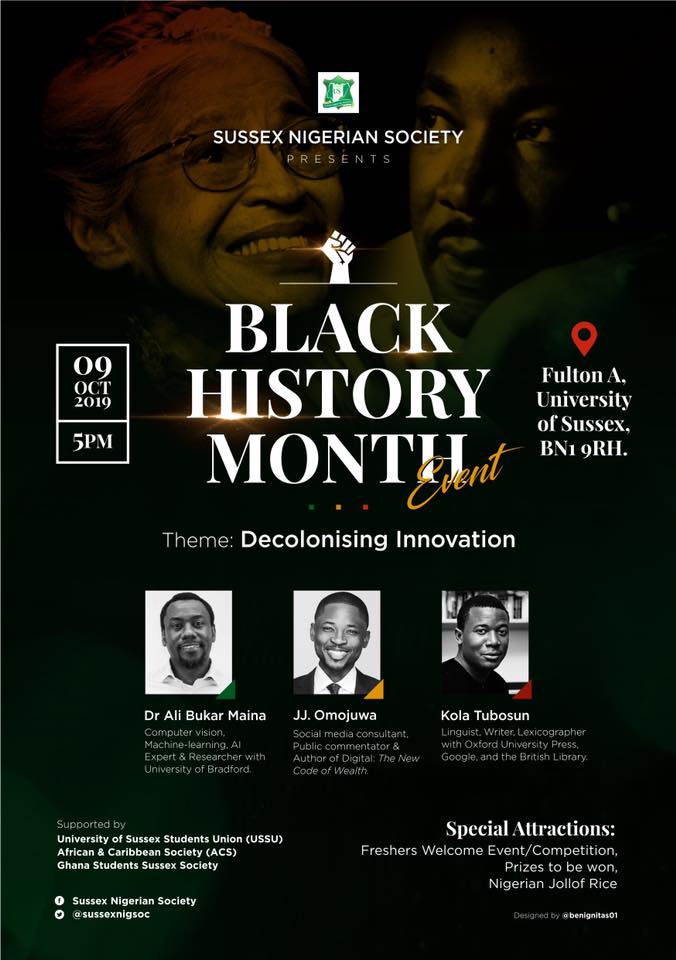

Being the text of a talk delivered at the Black History Month event at the University of Sussex on Wednesday, October 10, 2019

One of the things I remember while growing up in Ìbàdàn was that almost every technological item in the house was made in China. I knew this because it was written there: “Made in China.” It was hard to avoid. You just needed to look a bit under the item, or around it, and the sign was there: “Made in China.” I know this hasn’t changed as much today because a couple of weeks ago, my son, who is now almost six, asked me, “Is everything made in China?” He must have been observing too.

But it was not just electronic items that I associated with a particular place. I remember the razor blades we used — probably the same ones we still use in Nigeria — were made in Czechoslovakia. Well now, the country no longer exists, so it will now likely be written as “Made in Czech Republic”, but the association persisted long enough in my mind that I could not associate razor blades with any other place than Czechoslovakia, a country I could not place on the map, nor even properly spell if not for the razor blade.

Later as an adult, I would know of other places where technological or mechanical tools were manufactured. We learnt of Japan, and later Korea. Actually, today, many tools and items have become synonymous with those countries where they’re made. My mechanic would often say “This is Original! It’s not China. It’s Korea!” and I would automatically know what he means to say. When I visited Seoul in January of 2018, I discovered for the first time that Kia and Hyundai were made by the same company. I learnt that Honda and Hyundai were made in different countries (Japan and Korea respectively), and that Daewoo and Samsung were Korean companies, and not Japanese. Yes, I’m not very versatile in automotive news, but it was gratifying to find out that — after all — not everything was made in China.

When personal computers came to use in the late nineties and early 2000s, for some reason, the perception around their provenance was not Asian. Yes, intellectually, we could understand that the hardware was likely made in Asian spaces, but the idea of personal computers, made prominent by their software — this time Windows — was American. We associated it with Bill Gates and his company, Microsoft. And so another level of association took place and spread as the use of PCs themselves spread around the place. This phenomenon also conditioned how we reacted to the capabilities of these devices: they were American tools, and so they provided the user with an access one would expect for an American user. It made sense.

This was why when I got my first Personal Computer, in my second year of university, around 2002, I understood — or let me say surrendered to — the idea that it could only type in English. Whenever any word was used that was not in English, or that the computer did not recognize, it underlined it with a red wriggly line. It was easy to excuse as ‘normal’ and expected. The PC was an American invention and so there was nothing to complain about. After all, it could do other things like play Prince of Persia, a game about castles, Mullahs, and princesses. It could also play Fifa 98, a simulated soccer game that got our endorphins rushing whenever we had free time to indulge in it. It could play Chess, a game invented in India at around the 6th Century AD and perfected in Europe. In short, it did the ‘expected’ things.

But I was not satisfied, though there was nothing I could do about it. When I started working on my final year project, which was called The Multilingual Dictionary of Yorùbá Names, I complained but ultimately accepted that the computer couldn’t properly tonemark the names I was compiling in the proper way. When my professor gave us homework to translate technical terms in electrical engineering or mechanical engineering into our local languages, I turned mine in with the Yorùbá terms written in the Latin script without the tone markings that properly disambiguates the words. He probably didn’t notice, nor care — again, we used the same computers, so he was familiar with the obstacles — but it distured me. I was not satisfied.

It was the same dissatisfaction I would feel when Twitter, in 2011, announced that they were opening the platform for translation into many world languages but excluded any African languages from the list. It was the same way I would feel realizing that Siri, that automated computer voice on the iPhone and iPad existed in Swedish (~10.5 million speakers), Norweigian (~4.32 million speakers), and Danish languages (~5.5 million speakers) but not in Yorùbá (with over 40 million speakers). It is the same disappointment I would feel reading Nigerian writers write in English with proper attention to the diacritics of foreign words like French or German or Swedish, but total disregard for words in their own language in the same text.

In all, there seemed to be a perception that things were only meant to be in English, meant to be in a European language to be proper. When I used to teach English in a high school in Nigeria, a colleague of mine — ironically also a graduate of linguistics — said it was ‘unprofessional’ to speak Yorùbá, or any Nigerian language among members of staff while in school. I asked him if he’d feel the same way if the language being spoken among the staff was French or Spanish. He said ‘No, that is different.’ I couldn’t see the difference at all. In Kenya, students and teachers are allowed to speak any Kenyan language, along with English, while in school, and there is nothing wrong with it. In Wales, schools now exist where Welsh is used as a medium of instruction. Why, after fifty nine years of so-called independence from Britain do we still need our educational system to reflect British ideas of propriety, British sensibilities, or British manner of speaking?

When the Nigerian English accent on Google was launched in July, the responses were mixed, as is usual for most things in Nigeria. But some of the negative comments were curious because they were not based on whether the voice mispronounced things or any other objective disagreement. They hated it because it was a “Nigerian” voice. Someone tweeted something to the effect of “Why do I have to listen to a ‘local’ voice for Christ’s sake?” And there were others who said something like “Why do I want to hear a voice that sounds like mine?” So, in all, there seems to exist, even if not in the majority, a part of our society that resists anything that actually empowers us to be ourselves, or to see ourselves reflected in technology. I have seen journalists speak with taxi and Uber drivers, who actually use the voice every day, and are grateful that they have a computer voice that can correctly pronounce “Lekki-Epe Expressway” or “Ajọ́sẹ̀ Adéògún Street” or “Okokomaiko”. These are incremental ways in which we are decolonizing technology.

But innovation itself, as today’s topic suggests, is what needs decolonizing, which is a more fundamental dimension. Why, for instance, are students denied access to universities because of a lack of a ‘credit’ grade in English? Yes, the answer is because English is the primary means of teaching in our universities. But why is this so? Why is this one of the things we have accepted without question? Could it be that we can never pass down knowledge of complex ideas in education unless it is in English? This cannot be the case. Imagine Albert Einstein, who spoke German as a first language, and who may not have left Germany had Hitler not taken over, being denied access to a university education because of his lack of English competence! Education and knowledge, for some reason, have been conflated with English language competence, which it should not be. Kia, Hyundai, Samsung, Sony, etc, and even the makers of the razor blade we still continue to import in Nigeria are proof that it is not the language you speak that determines your future, but the knowledge with which you deploy the language, and the use to which that knowledge is put.

So, today, there is a Nigerian English accent on Google Assistant and Maps. Other Nigerian languages might follow. Twitter tried to create a Yorùbá language platform. At YorubaName.com, we created a free tonemarking software which can be used to properly write/type the language on your computer and on the internet. And at TTSYoruba.com, in 2016, we created the first text-to-speech application for Yorùbá. These are very few in the resources that would be needed to empower the African to use technology. I mean, you still can’t use an ATM in Nigeria today in any Nigerian language, so there’s still a long way to go.

But using technology that has been brought to use from the outside — even in our own language — is not enough. Not by far. We need to be able to think —using our own native knowledge — to create tools that can not only empower us and solve our problems, but also solve the world’s problems. Someone sat down and invented a car. Someone invented companies that make more fuel-efficient cars, and electric cars, and the radio, and computers. They come from different language and cultural backgrounds, but the common thing with all of them is the spirit of innovation, and the absence of a limit placed on them just because of their first language. It doesn’t matter that the creator of Kia or Honda do not speak English nor does it matter that the person buying the car does not speak Korean or Japanese. How do we get to this stage with our own ideas? One way, of course, is to stop limiting ourselves and our imagination.

When we no longer create needless obstacles for ourselves, either in the form of language discrimination in education or politics, then the change can truly begin. My obsession only happens to be language and technology and literature, and ways to decolonize them as much as possible, providing opportunities for our inner selves to thrive. There are still so many other ways in which we can achieve freedom from the constraints we put on ourselves, using other skills and competencies. I am glad to be able to do mine with the skills I have. And, sometimes, that’s all one can ask for.

I thank you for your time.

No Comments to Decolonizing Innovation | Speech at Sussex so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)

No one has commented so far, be the first one to comment!