Every once in a while, a conversation returns to my timeline about the meaning of ‘akata’, the origin, the use, and other social dimensions of its existence in the relationship between Africans on the continent and those in America. Discussions are had and the issue goes away, only to return in another form at another time. Yesterday was one such event when, shortly before going to bed, someone tagged me on Twitter about the meaning of the word again. I shared photos of the entries in two of my dictionaries and thought that was all.

I found out, later, that the invitation came from a bigger context: an apology by my colleague and language professor, Uju Anya, for using the word in the past in different twitter contexts. The debate that followed was whether the word was a slur in the first place, whether she had the reason to apologise, whether those calling for her resignation were overplaying their hand about an issue of no relevance, or whether certain words are allowed a pass if the intentions are pure.

This time, I thought it best to put my thoughts down on what I know about the word, what I think about the perennial controversy. This essay draws from my experience as a linguist and lexicographer, native speaker of Yorùbá, and a scholar of history, especially of transatlantic slavery and attendant consequences.

What is akata?

Let’s start with the three meanings recorded in the Yorùbá dictionary:

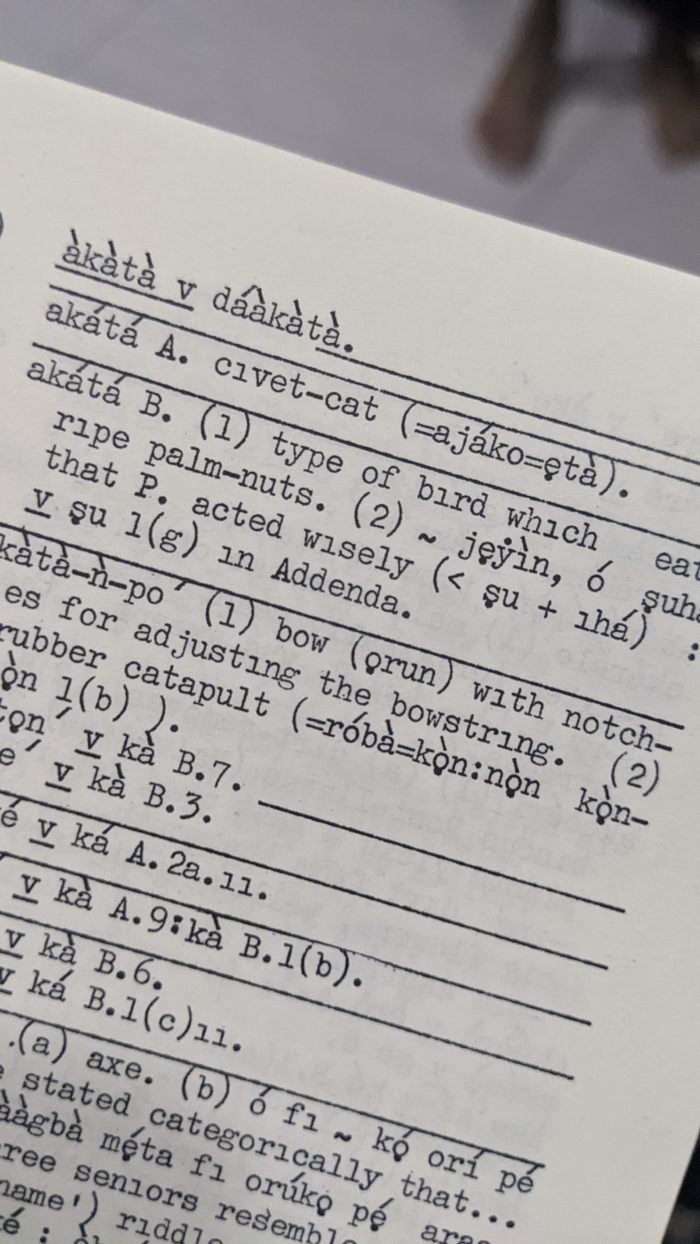

- n. Jackal, same as ‘Ajako’. Source: A Dictionary of Yorùbá Language by CMS (1913).

- n. Civet-cat. Also “ajáko ẹtà”. Source: Dictionary of Modern Yorùbá by R.C Abraham (1958)

- n. A type of bird which eats ripe-palm nuts. Source: Dictionary of Modern Yorùbá by R.C Abraham (1958)

As far as we know, the word doesn’t exist in any other Nigerian language.* It is a Yorùbá word — at least in its origin.

Is it a slur?

First, let’s start with history. Growing up in the eighties in Nigeria, I heard the word only as a descriptive term with no pejorative intent.

It was just any word, to refer to a certain demographic. We had òyìnbó for ‘white people’ (similar to muzungu in Swahili or onyi ocha in Igbo, or gringo in Spanish/Portuguese); we had akátá for Black Americans; we had Gambari for northerners in Nigeria (Sulu Gambari was the name of a famous Yorùbá-Fulani king in Ìlọrin); we had Tápà for Nupe people many of whom had intermarried with Yorùbá people; and we had kòbòkóbò for almost everyone else that didn’t speak Yorùbá.

Of all the terms, kòbòkóbò was the only one that seemed to carry a negative intent, because it referred to someone who, in the imagination of the Yorùbá person using the word, was not cultured enough to understand the language. The people we referred to with those words knew they were called that, and it never — to my knowledge — carried any negative blowback. It was used in film and popular culture.

There was a famous fuji music album by Àyìndé Barrister from the late eighties or early nineties in which he sang the following lines:

Akátá gba ‘jó

Òyìnbó gba ‘jó

Yorùbá gba ‘jó o

Translated:

American blacks danced to my song

American whites danced to my song

Yorùbás also danced to my song.

The album was one he waxed shortly after returning from an American tour, so it was a celebration of his popular appeal across different demographics. No slur in sight.

How did akátá even come to refer to African Americans?

No one has found any verifiable answer, but a plausible one goes like this:

In the sixties and seventies, African Americans channelled their social and political rebellion through the Black Panther movement, claiming an African cat as a symbol of their struggle for self-actualization. Yorùbá Nigerians in the States at the time, perhaps happy to participate, referred from then on to African Americans as akátá. It was not the exact Yorùbá word for panther**, but it was close. Whether that initial use was meant to be derogatory is something that needs to be researched, but there is no substantive proof of that, and many notable African scholars of Yorùbá extraction have written favourably about the Civil Rights Movement and all that came with it in the African-American struggle.

When/How did it become a slur?

It was when I became an adult that I started noticing different ways in which the word was used. Not just akátá, by the way, but also gàm̀bàrí and the others. You would hear someone being called gàmbàrí because he didn’t pay attention to instructions or appeared slow to act. Or for any random reason. This would be in-group conversations, particularly when no northerner was in sight. So it was not directed at the outsider, but at a Yorùbá person as an insult. The insult was to the Yorùbá target, not the northerner (even though the secondary insult to the northerner is also implied, but not overt). It is possible that akátá also then took on this character as time went on.

Such that almost every time I heard it from the early 2000s, it had a non-positive character. It was not a slur in a way that the n-word or even gàmbàrí was, that is, it was not a word that was used to insult a person to their face. In fact, I don’t think I recall any instance in which someone used akátá as a weapon. You can’t stand in front of someone and say “you bloody akátá”, it doesn’t quite work. But when it was used to refer to African-Americans, the meaning seemed to have changed. It could be about crime rates in the US, about any other unsavoury characteristic, or even about a normal or even friendly conversation. Which of those black people standing there do you want me to call? The akáta one? Okay. In fact, not many people today even know that it referred to a certain cat or bird — either of which are likely extinct anyway. You hear akátá and you think African-American. Not Obama, but Jesse Jackson. African parents could mention not wanting their children to “behave like those spoilt akátá kids” Or a man could tell his friend that his new girlfriend is an akátá; not as a pejorative but as a descriptor. Maybe it was the fact that such a word exists at all that referred to our black cousins on the other side of the Atlantic that brought the pejorative colouring; or maybe because people started saying it meant “wild animal” or maybe it was because of the conspiratorial way in which I’ve heard people use it as if in a secret code to prevent the subject of the conversation from knowing that it’s them to whom the word refers. There was just some othering seemingly implied in the common contemporary usage that perceptive listeners started to decry. The word itself had not changed, but it was no longer possible to call it just a descriptor.

But as with when meanings of words change everywhere, there are still people in Nigeria today who knew the word only in its first cross-continental non-negative use. People of my parent’s generation fall into this category. In normal everyday conversation, they will use akátá to demarcate an African in America from an African-American. They do not know it any other way, because we never found another word for that demographic. There are also other people, who don’t speak Yorùbá, who have only encountered the word from other Nigerians or from other Africans, and just continue to use it.

Does intention matter?

This is where the debate gets interesting: the question of whether one should mean to denigrate before the meaning of a word is called into question. This is a big ongoing debate. Not just with the n-word but also with words in other domains. Even the word ‘òyìnbó’, which I mentioned earlier, got me thinking a few years ago, after a white student asked me in class if it was a slur. I knew that it was not, but I realized, in explaining to her, that I couldn’t successfully convey all the contexts in which we use it without raising her suspicion that I was hiding something. I wrote an essay instead, but the response I got to it, especially from Nigerians, showed me that even the question of whether the word could be derogatory in certain contexts was not one that people wanted to have. “If we don’t mean it to be offensive, then why should we listen to you who say you find the usage uncomfortable?” the argument went. If you told my mother that akátá was derogatory, when she had not used it in that way, she would strongly object. I can point her to African-Americans finding it objectionable, so she might not use the word in public, but it won’t be because she believes that she’d done something wrong.

Recently, Beyoncé conceded that her use of spazz was ableist and she had it removed from an album — even when she didn’t have such an intention from the start. The word ‘negro’, which started as being just descriptive, is no longer in fashion today, because of the other connotations it took on in the hands of a more powerful culture. Shouldn’t akátá suffer the same fate?

I’m of the opinion, knowing how I’ve seen the word used, that we lose nothing by no longer using it for anything other than the animals. But I am also sympathetic to those who recognize their past usage, and apologise for doing so. I don’t expect that every Nigerian knows the origin of the word or the ways in which modern usage seems to have perverted it. The only thing we know is that African-Americans do not like it as well, and that should be enough, especially if the purpose of the conversation is to improve relations across the pond.

But the word won’t go away, because not every Yorùbá speaker lives on the internet or care about language-based social crusades, and because words don’t just disappear. Gringo and mzungu will continue to be in use, even if we can point to instances in which their usage is problematic. All we can do is continue to have the conversation.

Should anyone who uses it be cancelled?

No. As with many things, intent matters. So does knowledge, and one’s response to new information. We continue to evolve as a society, and so will our use of language and interaction with each other. Not every African-American is insulted by akátá either, perhaps because not every one of them has heard it, and some who have don’t care, unless they encounter it first through an online essay in which the meaning of the word is put as “cotton picker”, which it has never been. But many deeply resent it, either because of what they think it represents or just because of the othering implied in the way it has been used over the years. This is valid, and Africans should absolutely take it into account when they speak. My recommendation is that we stop using it totally to refer to anything but the animal. But I know that I’m not in the majority. If this is your first time hearing the word, all you need to know is that the origin is benign, its growth in use is muddy but complex, and that there are people from the language community where the word originated who never use it, just as there are some who don’t have any other way, but mean absolutely no harm.

____

* I’ve been informed on Twitter that there’s another “akata” in South-south Nigeria, which is a common personal name.

** Update (August 20): The entry for ‘Panther’ in A Dictionary of Yorùbá (1913) lists these two answers: n. àmọ̀tẹ́kùn, akáta

No Comments to Is Akátá a Bad Word? so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)

No one has commented so far, be the first one to comment!