On the last Sunday of 2024, I hosted an event at the J. Randle Centre in Lagos, a newly opened and appropriately named “Centre for Yorùbá Culture and History.”

The well-attended event was a screening of Ebrohimie Road: A Museum of Memory, a new documentary film I wrote and directed, which examines the story of Wọlé Ṣóyínká as a young academic at the University of Ìbàdàn in the early sixties, and all the many implications of his stay there — and the house where he lived — on the Nigerian story and the conversation around memory, trauma, and legacy.

The movie was first screened in July 2024, and has travelled around the world, winning three film festival awards, and earning a dozen other official selections and shortlists. It has screened in many important places in Nigeria, including the Alliance Francaise Mike Adénúgà Centre, the Muson Centre, the University of Ìbàdàn, University of Lagos, Korean Cultural Centre Abuja, and many more. We always wanted it to return to The J. Randle Centre particularly because Ṣóyínká had mentioned it as the permanent home to some of his carvings collections which took a central role in the film, and for other personal reasons.

My relationship with the Centre dates back to its early conception — at least as early as 2016 or so — when Ṣeun Odùwọlé, a visionary architect, first showed up at my office at Google to discuss his burning idea for a visually-appealing museum of world status at that location that already held enormous historical significance for Lagos. The space was at the time a pile of debris, walled off from the neigbourhood after the demolition of the earlier structures and the famous swimming pool. Odùwọlé had secured the cooperation of the then administration of Governor Akínwùnmí Aḿbọ̀dé and other international partners to create something much more than a recreation centre: A Yorùbá Centre that would house the heritage of a people, and show a more competent presentation of history than the National Museum across the road belonging to the federal government.

I was enarmored by the idea, but much more by Odùwọlé’s zeal, vision, and ambition. Not much of any of the promised funds and support had materialized at the time, but the concepts were present on his computer, with images of what the building would look like, and what an experience of visiting the future Centre would look like, combining traditional curatorial practice with modern technology. I shared some of my ideas and promised personal cooperation. I visited for the first time in 2019 to see the construction taking shape. Some photos below from March 2019.

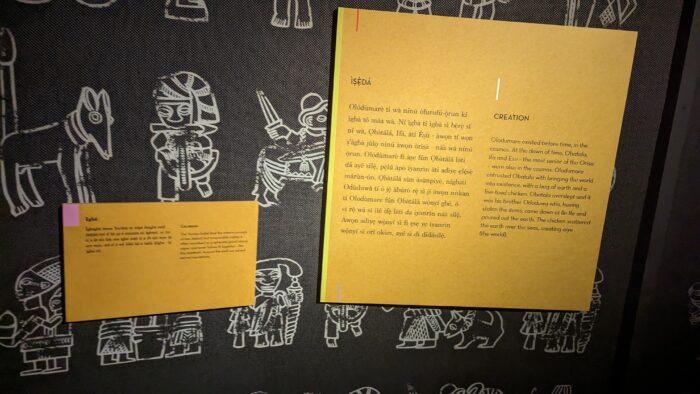

We kept in touch over the years, and as the idea grew. And when a team was put in place to design the curatorial materials for the Centre, I joined more formally, working with scholars across the world like Jacob Olúpọ̀nà, Will Rea, Rowland Abíọ́dún, and dozens of others, to put important ideas about Yorùbá identity in black and white for the future website. The texts would be in English and Yorùbá, with the latter taking a more prominent role. I worked with Odùwọlé to procure rare books and materials for the museum, and led the translation of all relevant texts between languages. While supervising the construction of the site, Ṣeun continued his networking tasks of keeping important partners across the world to their promise. The Lander Stool, for instance, was one of the items he unofficially secured for a permanent loan/return to the museum.

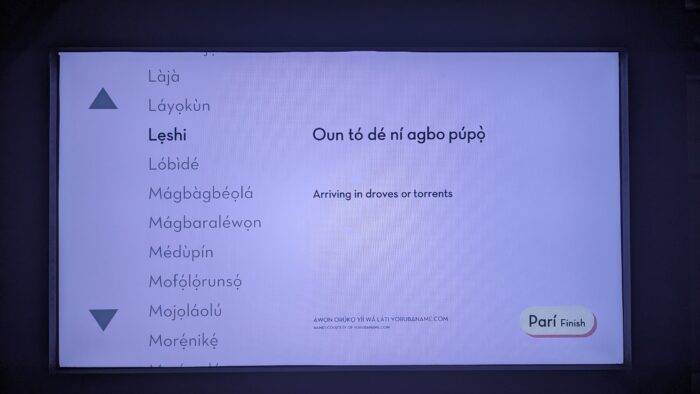

The work on the texts took months of research and editing, and finally the work was done. Even the signage and instructions at the Centre was to be written in both Yorùbá and English, as befitting such an important representation of culture. You can see the result in the architectural design of the screening venue: Yorùbá town names designed and well tone-marked forming a natural frosting on the glass.

And then things went quiet.

Through the defeat of Governor Aḿbọ̀dé in the 2018 primary of the APC and the emergence of a new governor in the person of Babájídé Sanwóolú, the work at the Randle Centre seemed to have stalled. It was no longer clear if it would proceed at all, or whether the commitment of the state to it would last beyond one administration. Even the idea of the centre as an independent custodian of culture working only with the state as a major partner seemed doomed. Politics, it appeared, had emerged to scuttle what had promised to be a departure from such typical Nigerian malaise.

In the intervening period, the transition between two administrations seemed to also lead to a transition for Odùwọlé, who had conceived and brought the idea to life through grit, hard work, and what I know to be an individual obsession. Such that when the Centre officially opened in 2024 finally, after having stayed locked for two years since its commissioning by the Head of State Buhari, the vision that brought the project to life was conspicuously missing. The website that had been created and curated with enormous research efforts had been allowed to lapse, and the only thing left was a building structure which, though still impressive in its design, content, and presentation, continued to need more intentional curatorial and intellectual handling.

With embarrassing events like this recent ‘invasion’ of the property by the state’s Commissioner of Culture confronting the centre’s appointed CEO for some inscrutable lack of deference [later explained as the establishment of an unauthorized business on the premises], it’s obvious that The J. Randle Centre needs proper intervention to make it live up to its founding ideals if it were to survive. There are sufficient examples of projects with ambitious goals like this failing because of a lack of proper structure and management system. And there are projects with far smaller budgets across the world which have been used to great success as generators of revenue and celebration of national heritage.

In this case, it is important for the Lagos State Government to provide answers to a number of important questions now arising:

- Whether the J. Randle Centre is a private event centre or a public one. Whether the state intends to continue to run it directly (through the commissioner) or via proxy. Which is more efficient, and why?

- How much the state is currently running the Centre with, and to which directions — including whether the state investment is bringing sufficient returns.

- Into which pocket the monies paid by visitors to use and visit the centre go, and how are they accounted for?

- Why a fully-transparent management board hasn’t been convened through which the Commisioner and members of the public can get answers to any questions they have without resorting to such a public spectacle as we saw today.

- When the original website and its important supplementary content will be brought back, so that the Centre isn’t just a space for Instagram reels but a true institution of learning and cultural engagement as the architects envisioned it.

Smarter people than me continue to add important points to the conversation via twitter. You can see them here, here and here. There seems to be a consensus that a more formal professional management board is sorely needed, and urgently, so as to elevate the place beyond another failed government edifice many of which already litter the land. In 2025, we need not continue to fall victim to “the Nigerian factor” in the area of arts and public engagement. We have seen how it’s done elsewhere — and they don’t have two heads. A better way forward is certainly needed.

No Comments to What’s Happening at Randle Centre? so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)

No one has commented so far, be the first one to comment!