The test of students’ progress is not always as tricky if one is lucky to have listened to the students beforehand and to have understood what they are used to and what they are not. In most cases, as long as the teacher knows that his purpose in the test is not just to surprise and attack but to monitor his own progress, there would be less tears and heartbreaks when the day is over.

The test of students’ progress is not always as tricky if one is lucky to have listened to the students beforehand and to have understood what they are used to and what they are not. In most cases, as long as the teacher knows that his purpose in the test is not just to surprise and attack but to monitor his own progress, there would be less tears and heartbreaks when the day is over.

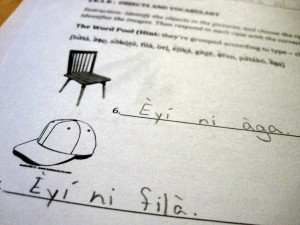

A few days before our mid-term test, I had given the students a list of areas to focus on, as well as how exactly to answer specific type of questions. There should be no one-word answers to questions requiring full sentence responses. There would be extra credit points for those who put the correct tone marks where necessary. There would be questions on personal introduction, identifying objects, numbers and greetings. And lastly, they should go over virtually everything we had learnt in class. After all, it was supposed to be a test of ability as well as hard work.

Beside the thirty questions that covered all we had learnt in class, there were also five extra-credit questions meant to help whomever needed it to get their grades up, and the questions there included “Kíni orúkọ olùkọ rẹ?”, “What is your adopted Yoruba name, and its meaning”, “Who is the author of the class novel ‘A Mouth Sweeter Than Salt’”, “Where was Suzanne Wenger originally from?” and “What’s the word for ‘zero’ in Yoruba?.

I have now finished marking (or scoring/grading in American English) the tests, and beside an overwhelming joy at how good they performed, I have made a few prominent observations:

- That none of them remembered my surname. It must have either been too long to remember.

- That many of them spelt “Good Afternoon” as “kassan” instead of “kaasan”. I’ve now told them that Yoruba does not have consonant clusters. That’s why when the word “brother” enters the language, it is pronounced as bùrọdá.

- That only a few of them knew the name of the author of the class novel. A few more remembered only the first name and not the surname, while a few knew the surname but couldn’t spell it.

- That everyone remembered the Yoruba word for “zero”.

- That some of the students studied beyond what they were taught in class. A case in point: even though I didn’t ask for plurals, a student responded to a question on identifying pens as “èyí ni awọn gègé.” (trans: here are some pens). I found that very impressive, and she was rewarded extra for it.

- That almost a quarter of the class didn’t remember their adopted Yoruba names, and half of those who did had forgotten the meaning. It was sure that they were not expecting to be asked about this in the exam.

- That some students would just NOT read the instructions on the exam question paper no matter how many times they’re told to do so, and notwithstanding the same instruction having been previously stressed again in the exam review materials.

- That there is always one student in class who would not perform well no matter how much help the teacher gives. S/he is either just lazy, or dull. The problem is, they are the ones who do not speak up when they don’t understand, for fear of being too prominent, when they should ordinarily be the most vocal.

I have my work cut out for me for the next half of the term.

1

Bola at http://YourWebsite

Well done! This little mid term report makes me wish that you were teaching Yoruba in London. (Our own teacher is a guest lecturer in Ikire this year.)

Posted at October 17, 2009 on 5:15am.

2

Yemi Adesanya at http://YourWebsite

Were some of those questions written in English?

I like the idea of grade booster questions.

Posted at October 19, 2009 on 2:26pm.

3

Kola Tubosun at http://www.ktravula.com

Yea, there were some questions written in English, like four of the grade booster questions.

All the instructions were however all in English, and only a few questions were framed in Yoruba. Like “Kini oruko re?” and “Nibo lo n gbe?” etc.

Posted at October 19, 2009 on 2:54pm.