A little after we left Cahokia on Saturday, we headed to the St. Louis to visit the state of Missouri’s most famous landmark – the St. Louis Gateway Arch, also called the “Gateway to the West” because of its place in history as the spot where the first expedition to the Western part of the United States began. It is an integral part of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial and it is the iconic image of St. Louis, Missouri. I’d always wished to go to this monument, right up to the top, even in my supposed fear of heights, but on Saturday, I got my wish.

A little after we left Cahokia on Saturday, we headed to the St. Louis to visit the state of Missouri’s most famous landmark – the St. Louis Gateway Arch, also called the “Gateway to the West” because of its place in history as the spot where the first expedition to the Western part of the United States began. It is an integral part of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial and it is the iconic image of St. Louis, Missouri. I’d always wished to go to this monument, right up to the top, even in my supposed fear of heights, but on Saturday, I got my wish.

The St. Louis Arch is located along the Mississippi river and close to the road bridges that connect the states of Illinois and Missouri. It is called the Gateway to the West because of the role it played when officers Louis and Clark set out on the orders of then President Thomas Jefferson to discover what lay further west of the country via the Mississippi river, once considered the longest river in the world. The Arch, an architectural wonder made out of cement and stainless steel, has always been the most visible monument in the state, and it’s considered the tallest monument in the United States at 630feet. It is visible in most if not all parts of the city.

The St. Louis Arch is located along the Mississippi river and close to the road bridges that connect the states of Illinois and Missouri. It is called the Gateway to the West because of the role it played when officers Louis and Clark set out on the orders of then President Thomas Jefferson to discover what lay further west of the country via the Mississippi river, once considered the longest river in the world. The Arch, an architectural wonder made out of cement and stainless steel, has always been the most visible monument in the state, and it’s considered the tallest monument in the United States at 630feet. It is visible in most if not all parts of the city.

The most fun part of the trip, of course, was going up to the top of the steel structure to look down at an expanse of the city’s land. A trip to a tall monument is never complete without a journey up to its summit. In this case, the lift was a little box that accommodated only five people, and took four minutes to get to the top. The first question in my mind had always been: how does an elevator work in such a steel structure as one curved as an arch? My question was answered amidst bouts of claustrophobia. It moved up the arch, quite logically, in an arched form, slowly until it reached the top while giving those in the small elevator a view of the steps as we went up. Apparently, it is also possible to ascend it by way of one’s feet, though I don’t know how long that would have taken. In any case, the stairs were closed to the public, and I don’t know how long it’d been like that.

At the top, we got off and walked up the flight of a few steps into the observatory itself where we were able to look down out of a series of windows. Even though it didn’t shake with the wind that must have been blowing outside, and even though there had never been a terrorist or vandalism attack on the monument that could have given me given me fright of death or falling, I felt a little afraid looking into the river from over six hundred feet above the earth. What if? There was a helicopter landing pad nearby where one landed and shortly took off. From afar, I could see that it was a tourist helicopter – for hire – and not a police one, so I wasn’t immediately relieved from my anxiety. If anything had happened while we were up there, I’d probably be long dead before landing on the pavement below, except I was lucky to have been blown by a strong wind right into the Mississippi river.

At the top, we got off and walked up the flight of a few steps into the observatory itself where we were able to look down out of a series of windows. Even though it didn’t shake with the wind that must have been blowing outside, and even though there had never been a terrorist or vandalism attack on the monument that could have given me given me fright of death or falling, I felt a little afraid looking into the river from over six hundred feet above the earth. What if? There was a helicopter landing pad nearby where one landed and shortly took off. From afar, I could see that it was a tourist helicopter – for hire – and not a police one, so I wasn’t immediately relieved from my anxiety. If anything had happened while we were up there, I’d probably be long dead before landing on the pavement below, except I was lucky to have been blown by a strong wind right into the Mississippi river.

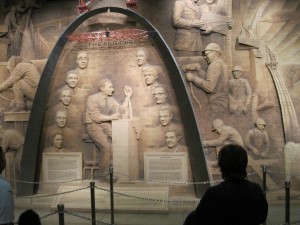

But we were lucky, Reham and I. There were no attacks, and the uniformed officers on the observation deck with us didn’t have any work to do while we were up there than to pace up and down observing everyone as they did so. When we got enough of our shots up there, we went back down the same way we came, this time faster. It is always easier coming down in an elevator than going up. We then went around the gift shop, and later into the theatre within the complex, to see a documentary movie about the expedition of Louis and Clark, also eponymously titled, before going into the museum where we saw even more of the Native-American history. The famous expedition of officers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark did more than open up the American West to European civilization. It also served as the beginning of the great incursion of European settlers into a part of the country never before inhabited by people other than the indigenous Native Americans (also called the American Indians). The expedition achieved the main purpose of mapping the area, discovering the path of the Mississippi, and conveying to the native Indians that the land no longer belonged to them but to the white men – the real beginning of their gradual decimation.

But we were lucky, Reham and I. There were no attacks, and the uniformed officers on the observation deck with us didn’t have any work to do while we were up there than to pace up and down observing everyone as they did so. When we got enough of our shots up there, we went back down the same way we came, this time faster. It is always easier coming down in an elevator than going up. We then went around the gift shop, and later into the theatre within the complex, to see a documentary movie about the expedition of Louis and Clark, also eponymously titled, before going into the museum where we saw even more of the Native-American history. The famous expedition of officers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark did more than open up the American West to European civilization. It also served as the beginning of the great incursion of European settlers into a part of the country never before inhabited by people other than the indigenous Native Americans (also called the American Indians). The expedition achieved the main purpose of mapping the area, discovering the path of the Mississippi, and conveying to the native Indians that the land no longer belonged to them but to the white men – the real beginning of their gradual decimation.

The Arch has been called “A Monument to Dreams” perhaps because of its architectural pace-setting significance. Standing beside its base, scratching one’s name on its stainless steel where hundreds of names from all over the world have littered, looking down from its top or seeing it at night from any of the spots in St. Louis, it is definitely a wonder to behold. But at the end of the excursion, Reham remarked to me while we sat in the hall with a cup of coffee each in our hands, “If we hadn’t gone to Chicago, K, this would have been so impressive.” and I nodded in immediate unexplainable agreement. And even though I had enjoyed myself in some way, and was glad to have ticked the St. Louis Arch off my list of to-visit places, with enough souvenir and museum gift items to show for, the visit just happened to have lacked a certain kind of ktravula excitement. It could be from lack of adequate sleep the previous night. Nevertheless, I am glad that I went.

7 Comments to Defying Gravity so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)