Dark shades to hide the sun and a Hawaian type T-shirt for a warm day, I packed my travelling kit on Sunday and headed out to Badagry. The coastal town off the Atlantic ocean is famous (or notorious, as the case may be) for being the biggest slave port in south west Nigeria during the days of slavery.

Dark shades to hide the sun and a Hawaian type T-shirt for a warm day, I packed my travelling kit on Sunday and headed out to Badagry. The coastal town off the Atlantic ocean is famous (or notorious, as the case may be) for being the biggest slave port in south west Nigeria during the days of slavery.

Ruled by white-cap feudal chiefs originally from Dahomey, with a strong military empowered by the proceeds of slavery, Badagry lays claim to having sold millions of people captured from parts of Nigeria to the Portuguese and other European traders who came in droves in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries.

The Badagry Heritage Museum, now housed in the former district office, was closed. There was a young woman sitting by a table close to the gate, playing loud Nigerian hip-hop music. She did not stop us, so we walked around the deserted building, taking pictures and wondering what lay within its closed offices. The Heritage Museum building was built in 1863 – ironically the same year of the American Emancipation Proclamation – but is now in trust of the Lagos State Waterfront and Tourism Development Corporation. One question that lingered in our minds as we pondered the beauty of the old building and many others in the town was what, if one could guess, was this building used for in 1863?

Down the street from the Heritage Museum, on a road facing the lagoon, was Lord Lugard House, where the amalgamation of Northern and Southern Protectorate that eventually became Nigeria was signed. Lord Frederick Lugard was the first Governor General of the entity now called Nigeria, and his wife was said to have coined the name ‘Nigeria’ from the River Niger. He lived in the house while he administered the country.

Down the street from the Heritage Museum, on a road facing the lagoon, was Lord Lugard House, where the amalgamation of Northern and Southern Protectorate that eventually became Nigeria was signed. Lord Frederick Lugard was the first Governor General of the entity now called Nigeria, and his wife was said to have coined the name ‘Nigeria’ from the River Niger. He lived in the house while he administered the country.

Next to it is a white house that is the first storey-building in Nigeria. Painted white, it was the house in which the now legendary returnee slave boy, Bishop Ajayi Crowther, an Anglican Bishop, first translated the Bible from the English Language into Yoruba in 1846. The house was built between 1842 and 1845. Like the other two buildings, this too was locked, and from the fence all we could see was its back and a rusty metal signboard that lay on the floor with the inscription, ‘The Church of Nigeria. The Diocese of Lagos. Anglican Communion.’

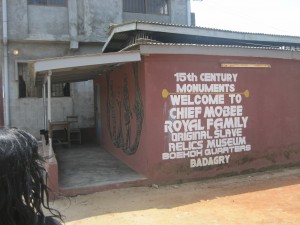

Mobee Street

Further down the road to the right was Mobee Street, named after the “royal family” of Mobee, who prospered for generations on the trade of slaves. Today, the family prospers on showing off relics of their family’s ancient trade to guests from all over the world willing to pay for it. I found this odd, and I said so to my co-traveller as we fished out the equivalent of one dollar each to gain entrance into the private museum that also houses the grave site of the first member of the Mobee lineage to “discontinue the slave trade”, Chief Sumbu Mobee.

Further down the road to the right was Mobee Street, named after the “royal family” of Mobee, who prospered for generations on the trade of slaves. Today, the family prospers on showing off relics of their family’s ancient trade to guests from all over the world willing to pay for it. I found this odd, and I said so to my co-traveller as we fished out the equivalent of one dollar each to gain entrance into the private museum that also houses the grave site of the first member of the Mobee lineage to “discontinue the slave trade”, Chief Sumbu Mobee.

In the small room that serves as the museum, the young man – also a Mobee – welcomed us and showed us the relics. “This is a neck chain,” he said. “It is used to lock the slaves’ necks individually like this.” He demonstrated, and allowed me to take a picture of him doing so. The privilege of bringing in a camera costs about $1.5 extra, though I didn’t know this at the time. He brought out another small piece of metal shaped like a triangle. “This,” he said, as he demonstrated again with his leg up on a stool, “is used to pin the leg of a stubborn slave to the ground. Like this.” He did the motion of a big hammer knocking the rusty metal into a man’s leg into the earth. It could only have been harrowing.

“This,” he said, showing me another instrument, “is used to lock the lips of other stubborn ones. With the lips through this hole, a spike is driven into it from the top and a hole is made. Then a padlock is applied, and the lips stayed shut until removed.” Next was the leg manacle that held the legs of two grown men together. I asked him if I could bring my leg forward as he tried in on, and he agreed. The two part curved metal rod that served as restraint on legs of two men was still strong and firm, as it must have been four hundred years ago. Each chain that extended from the ankles where the manacle was firmly clasped was heavier than can be assumed from just looking at it. The same kind of chain held two prisoners together by their necks and arms.

“This,” he said, showing me another instrument, “is used to lock the lips of other stubborn ones. With the lips through this hole, a spike is driven into it from the top and a hole is made. Then a padlock is applied, and the lips stayed shut until removed.” Next was the leg manacle that held the legs of two grown men together. I asked him if I could bring my leg forward as he tried in on, and he agreed. The two part curved metal rod that served as restraint on legs of two men was still strong and firm, as it must have been four hundred years ago. Each chain that extended from the ankles where the manacle was firmly clasped was heavier than can be assumed from just looking at it. The same kind of chain held two prisoners together by their necks and arms.

Walking just a few feet with these around my neck, I understood why only the strongest made it to the New World. It was understandable that, perhaps, less than a percentage of those captured even made it to the boat, and several thousands more died in the Middle Passage. The name Mobee, the guide explained, was acquired from what the Europeans perceived to be the chief’s invitation to them to pick up some kola to eat. “E móbì.” I had thought it was mobee: “I beg you.”

There was a small cannon on the table, another relic from the past. It was used to announce the arrival of a ship from the high seas, and also to announce a curfew in the town. After the sound of the third cannon at night, the curfew began until morning, and any freeborn caught during this time was enslaved. It was the law. “All this town was called the Slave Corridors,” the guide explained. According to a recent article by Henry Gates, most of the slaves from Nigeria were from the Igbo tribe. I could not get a definite answer to my question of just how the slavers got hold of Igbo men and women who lived far off across the Niger and brought them to Badagry and the other slave ports in the country, to be sold off. The most definite response I got was that the slaves were brought from everywhere, and even a resident of the town could be enslaved for walking at the wrong time of the night. To trade, the Europeans rejected the cowrie shells that was currency in Badagry. Instead, they traded by barter. One bottle of whiskey was equal to ten slaves. A big cannon was exchanged for a hundred. On one slave market day in Badagry, up to 300 slaves were sold, we were told. About seventeen thousand were sold per annum.

There was a small cannon on the table, another relic from the past. It was used to announce the arrival of a ship from the high seas, and also to announce a curfew in the town. After the sound of the third cannon at night, the curfew began until morning, and any freeborn caught during this time was enslaved. It was the law. “All this town was called the Slave Corridors,” the guide explained. According to a recent article by Henry Gates, most of the slaves from Nigeria were from the Igbo tribe. I could not get a definite answer to my question of just how the slavers got hold of Igbo men and women who lived far off across the Niger and brought them to Badagry and the other slave ports in the country, to be sold off. The most definite response I got was that the slaves were brought from everywhere, and even a resident of the town could be enslaved for walking at the wrong time of the night. To trade, the Europeans rejected the cowrie shells that was currency in Badagry. Instead, they traded by barter. One bottle of whiskey was equal to ten slaves. A big cannon was exchanged for a hundred. On one slave market day in Badagry, up to 300 slaves were sold, we were told. About seventeen thousand were sold per annum.

The Brazilian Baracoons

From the Boekoh quarters where the tomb of another member of the family, High Chief Makinde Mobee, lay with two goats resting on it, we moved further down the street to another compound that housed what is called a Baracoon. At the entrance was a large inscription that told us that we were entering the Brazilian baracoons owned by Seriki Faremi Williams.

From the Boekoh quarters where the tomb of another member of the family, High Chief Makinde Mobee, lay with two goats resting on it, we moved further down the street to another compound that housed what is called a Baracoon. At the entrance was a large inscription that told us that we were entering the Brazilian baracoons owned by Seriki Faremi Williams.

The baracoons were small rooms where up to 40 slaves were kept, all in upright position for days before they were shipped across the lagoon via the point of no return into the waiting ships. The group of houses, now mostly residential, were all at one point or the other used to keep slaves waiting to be transported. “Let me get the key,” a woman said after we indicated our wish to enter the baracoon. “It’ll be two hundred naira for one person,” she said. She must be either a descendant of the family, or the wife of one.

The room was ordinary, except for paintings on the wall showing Portuguese traders squatting before a turbaned chief, an umbrella over his head. The umbrella now lay in the corner of the room, a skeleton of its former self. There was another large picture on the wall. In it was Seriki Faremi Williams Abass himself and several of his co-traders – Africans and Europeans – in a group picture. This baracoon was his industry. Now as a relic, it still serves some purpose to his descendants.

“Here is the room that housed forty slaves,” she said as she led us in. It was dark in there. There was just one small window a foot in length on the topmost part of the wall close to the roof, sufficient only to let in barely enough air for five, much less forty people. There were ceramics and a few other fanciful things that could only have been received by barter from European traders. “How could this this room keep forty people?” I asked rhetorically, because from the smile on her face, it was clear that she did not correctly perceive the intensity of worry on my mind.

“Here is the room that housed forty slaves,” she said as she led us in. It was dark in there. There was just one small window a foot in length on the topmost part of the wall close to the roof, sufficient only to let in barely enough air for five, much less forty people. There were ceramics and a few other fanciful things that could only have been received by barter from European traders. “How could this this room keep forty people?” I asked rhetorically, because from the smile on her face, it was clear that she did not correctly perceive the intensity of worry on my mind.

In normal standing positions, the room would ordinarily not be able to hold more than twenty people of the size of the woman in front of us. “Some died too, I’m sure,” she said. In a showglass immediately outside the baracoon to the right was a rod with a spiral mouth. I knew what it must have been used for, but I asked anyway. “They used it to drill the legs of the stubborn slaves,” she said, still almost smiling.

Whispers from the waves

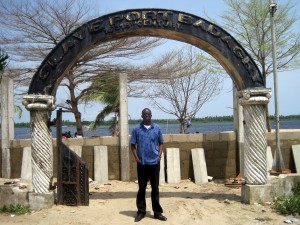

Time to go, we stepped out and walked to the bank of the lagoon across the road to see where slaves were initially loaded into the boat to be taken across to the Atlantic Ocean where the large ships lay. Nothing is there now, except two sinking canoes and a sign that says ‘Slave Port 16th to 18th century’. Barely 400 years ago, this town participated in one of the grossest abuses of human dignity.

Time to go, we stepped out and walked to the bank of the lagoon across the road to see where slaves were initially loaded into the boat to be taken across to the Atlantic Ocean where the large ships lay. Nothing is there now, except two sinking canoes and a sign that says ‘Slave Port 16th to 18th century’. Barely 400 years ago, this town participated in one of the grossest abuses of human dignity.

Today, only the whispers from the waves on the shore tells of how much pain its memory still brings. We didn’t get a chance to see the site of the famous agia tree under which Christianity was first preached. It was further away. Neither did we get to visit the ‘Point of No Return’. Descriptions were enough. It lay about one kilometre away from the shore at the other side of the lagoon.

But how could it be that the town that is famous for landmarks in Christianity, was even more so for one of the biggest ills of mankind? Slavery ended in the United States in 1863, in other parts of Africa in 1870, but in Badagry in 1886.

But how could it be that the town that is famous for landmarks in Christianity, was even more so for one of the biggest ills of mankind? Slavery ended in the United States in 1863, in other parts of Africa in 1870, but in Badagry in 1886.

Of all the things we were told as part of this tour, one of them that didn’t quite hold water – no pun intended – was the argument that any one person (Christian or not) descendant of anyone in Badagry put an end to slave trade. The available fact is that demand had only simply faded from where it came across the Atlantic, and the trade naturally suffered as a result. And in that sad fact lies another lesson in history.

____________

First Published in NEXT Newspaper on June 21, 2010.

4 Comments to Lessons on A Tour of Badagry so far. (RSS Feeds for comments in this post)