I have admired him from afar for a very long time, especially since he blossomed into our television screens towards the end of the last century as the director of Mainframe Films (Opomulero). However, his work and reputation extend way back to the history of television in Africa. As he told me recently on the movie set of a series of multilingual recordings of Public Service Announcements (PSAs) on the Ebola virus raging around the continent, he was there near the beginning, in Ibadan, when the then WNTS (Western Nigerian Television Service) was established. The station was founded in 1959, when he was still in primary school.

I have admired him from afar for a very long time, especially since he blossomed into our television screens towards the end of the last century as the director of Mainframe Films (Opomulero). However, his work and reputation extend way back to the history of television in Africa. As he told me recently on the movie set of a series of multilingual recordings of Public Service Announcements (PSAs) on the Ebola virus raging around the continent, he was there near the beginning, in Ibadan, when the then WNTS (Western Nigerian Television Service) was established. The station was founded in 1959, when he was still in primary school.

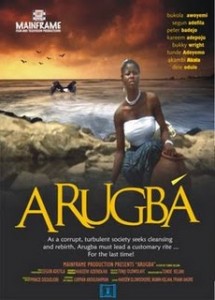

At that time, when the foresight of Western Nigeria’s first politicians brought television technology into the continent and sited it in Ibadan, a new industry of imaginative artists was created. And years after that innovation, the first set of broadcasters, technicians, scriptwriters, stage workers, costume and set designers, etc went on to become innovators of their own in various fields of endeavour. (My own father was one of those, joining the Western Nigerian Broadcasting Service (WNBS) in the late sixties as a reader and later, producer). Tunde Kelani became employed at the station as a trainee cameraman on September 20, 1970. According to him, that was when his career trajectory began. He later went to a number of film schools around the world in order to gain sufficient experience. In 1993, his first film as the director of Mainframe Ti Oluwa ni Ile, a trilogy, was released to critical acclaim.

At his Mainframe office in Oshodi, Lagos, the feel of a decent but relaxed artistic environment is prevalent. In a house that doubles as a studio with an editing room and other offices, TK holds court, providing needed input during movie shoots, and coordinating artistic directions where necessary. At 66, he shows no signs of slowing down. On this set, I’m an almost invisible adjunct, present to provide input about the multilingual scripts I worked on translating into the various Nigerian languages, while the actors come in and out to interpret and act their roles on set and against the blue screen. And while the recording goes on, and in-between takes, other light-hearted discussions take place. On set on these couple of days of shooting were Toyin Aimakhu-Johnson, Femi Sowoolu, Joke Silva, Kunle Afolayan, Yomi Fash-Lanso, Tonto Dikeh, Kabirat Kafidipe, among many others.

At his Mainframe office in Oshodi, Lagos, the feel of a decent but relaxed artistic environment is prevalent. In a house that doubles as a studio with an editing room and other offices, TK holds court, providing needed input during movie shoots, and coordinating artistic directions where necessary. At 66, he shows no signs of slowing down. On this set, I’m an almost invisible adjunct, present to provide input about the multilingual scripts I worked on translating into the various Nigerian languages, while the actors come in and out to interpret and act their roles on set and against the blue screen. And while the recording goes on, and in-between takes, other light-hearted discussions take place. On set on these couple of days of shooting were Toyin Aimakhu-Johnson, Femi Sowoolu, Joke Silva, Kunle Afolayan, Yomi Fash-Lanso, Tonto Dikeh, Kabirat Kafidipe, among many others.

But being around this legend of Yoruba cultural expressions in film, animated conversations ensue, taking us from one fascinating subject to the other. It has been said, for instance, in western media that Yoruba (or Nigerian) movie industry grew “out of nothing”, or out of little. That reiteration brought out the strongest rebuttal from TK who pointed out, correctly, that the Yoruba culture carried with it an element of theatre that thrived way before television came, and continued through the TV medium in the 50s to the current day. After all, there was Herbert Ogunde, and Moses Adejumo (Baba Sala), and Adeyemi Afolayan (Ade Love) way before the current crop that made what is now called (not to everyone’s satisfaction) “Nollywood”.

Animated even more by the presence of my British-Jamaican friend, psychologist and filmmaker visiting from the University of London, Dr. Julian Henriques, conversations moved from the challenges of movie production on the continent to the inevitable transition from old recording equipment to today’s modern cameras. Julian who was visiting Nigeria for the second time had, earlier in the day, visited with me the Kalakuta Museum in Ikeja, sharing an afternoon of conversation and wonder in the court of the late Afrobeat founder. His interest, Dr. Henriques, in sound as well as cultural movements and productions collided perfectly with the Kelani encounter, as their short but substantive conversations showed, and a happily saturated guest went home with a signed poster of the host’s new production. Julian’s feature film Baby Mother (1998), co-written with Vivienne Howard has been called a “vibrant and delightful” work, buzzing “with vitality and colour.” Baby Mother refers to what Americans call “baby mama”: women saddled with the responsibility of raising children from their unwed partners. The film is more than that though, touching on a number of relevant themes in black, British, and Caribbean popular culture. Here’s a brilliant YouTube clip.

Animated even more by the presence of my British-Jamaican friend, psychologist and filmmaker visiting from the University of London, Dr. Julian Henriques, conversations moved from the challenges of movie production on the continent to the inevitable transition from old recording equipment to today’s modern cameras. Julian who was visiting Nigeria for the second time had, earlier in the day, visited with me the Kalakuta Museum in Ikeja, sharing an afternoon of conversation and wonder in the court of the late Afrobeat founder. His interest, Dr. Henriques, in sound as well as cultural movements and productions collided perfectly with the Kelani encounter, as their short but substantive conversations showed, and a happily saturated guest went home with a signed poster of the host’s new production. Julian’s feature film Baby Mother (1998), co-written with Vivienne Howard has been called a “vibrant and delightful” work, buzzing “with vitality and colour.” Baby Mother refers to what Americans call “baby mama”: women saddled with the responsibility of raising children from their unwed partners. The film is more than that though, touching on a number of relevant themes in black, British, and Caribbean popular culture. Here’s a brilliant YouTube clip.

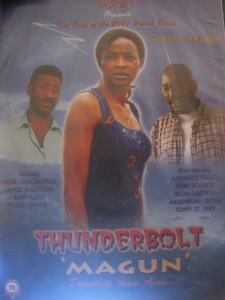

One of the other gems dropped in the conversations is the news of Tunde Kelani’s new project: a theatrical adaptation of Amos Tutuola’s The Palmwine Drinkard into Yoruba as Lanke Omu. According to TK, it is one that carries, for him, an immense personal satisfaction for its transmission of the text’s original intent into a new cultural medium. But that is not the only project on his hands. He had also just recently completed work on a film adaptation of a novel Dazzling Mirage written by Olayinka Egbokhare, which has already been screened for selected audiences. From his reputation and the artistic scope of his earlier works (Koseegbe, O Le Ku, Ti Oluwa Ni Ile, Saworoide, Yellow Card, and Thunderbolt come to mind), these two new projects promise even more, cementing a career that is as dynamic as it is emblematic of the best of African artistic and cultural expression in a world dominated by other global influences.

One of the other gems dropped in the conversations is the news of Tunde Kelani’s new project: a theatrical adaptation of Amos Tutuola’s The Palmwine Drinkard into Yoruba as Lanke Omu. According to TK, it is one that carries, for him, an immense personal satisfaction for its transmission of the text’s original intent into a new cultural medium. But that is not the only project on his hands. He had also just recently completed work on a film adaptation of a novel Dazzling Mirage written by Olayinka Egbokhare, which has already been screened for selected audiences. From his reputation and the artistic scope of his earlier works (Koseegbe, O Le Ku, Ti Oluwa Ni Ile, Saworoide, Yellow Card, and Thunderbolt come to mind), these two new projects promise even more, cementing a career that is as dynamic as it is emblematic of the best of African artistic and cultural expression in a world dominated by other global influences.

Though meeting him this time for the first time at close proximity, conversations illustrated that the trajectory of my creative and professional life has passed through courses in TK’s neighbourhood. I remember, for instance, his presence at the launch of the African Language Technology Initiative (ALT-I) in Bodija, Ibadan, in 2004 where my friend, mentor, and occasional collaborator Dr. Tunde Adegbola, burst into Linguistics all the way from Engineering, in a public way, during the WALC 2004 conference. It turned out that the link between Dr. Adegbola and Baba Kelani went even further back to many years pre ALT-I days in Lagos. Another friend, teacher, and mentor, Dr. Larinde Akinleye (now deceased), was a prominent cast in many of TK’s earlier movies. And the author of TK’s recent work, Olayinka Egbokhare, is a personal friend, as one of my teachers of Communication while in the university. It was like a reunion with a friendly but famous uncle you never knew you had, in an environment of mutual respect and admiration.

Also, a fascinating encounter.

______

[Watch the newly released Ebola PSAs here.]