(Being a paper delivered at the PyeonChang Humanities Forum at the Seoul National University Seoul, South Korea, on January 20, 2018 by Kọ́lá Túbọ̀ṣún. The audio recording of the talk can be found here)

Ẹ káàrọ̀ o. Good morning. Annyeonghaseyo.

First of all, let me express my profound appreciation to the organisers of this event for choosing me out of many to be here, among all these important people from around the world, to give you my own perspective on an important discussion. These are precarious times. And to be here in this place at this time to give a talk on a topic that is dear to my heart, is an honour. So, thank you. As we say in my language, adúpẹ́. I bring you greetings from West Africa.

I am here to speak about poverty. But before you assume that I am going in a predictable direction you have been familiar with from watching cable news from your different parts of the world about Africa, let me advise that you set a different expectation. My talk is about a different kind of poverty, one caused by exclusion, and one relating to one particular type of exclusion: language.

I come from Nigeria, a country of about 170 million people with over five hundred different languages and cultures. It is a place that offers as diverse a landscape in terms of both viewpoint and attitude to life. On the one hand, binaries can be found: The north is mostly conservative while the south is mostly liberal. The north is mostly arid and desert while the south is mostly rainforest and humid. On the other, we have an assemblage of cultures and languages which range from mildly intelligible dialects to distinct languages with no discernable cognate, even when they live around each other. This has made my country, Nigeria, a country created from a British colonial experiment, a very interesting place. From what I have read, this is not the same as what obtains here on the Korean peninsula, where Korean is generally described as a “language isolate”, with no discernable genetic or genealogical link with any neighbouring tongues.

Human migration and mandatory inter-mingling of tribes ensured that we are all exposed, in some way or the other, to characteristics of each other’s culture. Through warfare, conquests, and other forms of domination, a number of us have also become subservient, linguistically, to some larger languages around the country, such that, before the British came to colonize the whole swathe that makes up the country Nigeria, a certain linguistic mosaic had emerged. A mosaic, because it was not just one language which every others must speak, but several big languages, and several small ones, each occupying a particular space in the society, fulfilling particular roles in facilitating contact.

Human migration and mandatory inter-mingling of tribes ensured that we are all exposed, in some way or the other, to characteristics of each other’s culture. Through warfare, conquests, and other forms of domination, a number of us have also become subservient, linguistically, to some larger languages around the country, such that, before the British came to colonize the whole swathe that makes up the country Nigeria, a certain linguistic mosaic had emerged. A mosaic, because it was not just one language which every others must speak, but several big languages, and several small ones, each occupying a particular space in the society, fulfilling particular roles in facilitating contact.

I bring up the linguistic character of my hometown to create an image in your minds of both diversity and richness. Even many decades after the colonial processes that were set in place to create a homogenous society out of colourful and diverse peoples, the mosaic is still evident, though not in as bold a colour as was many years ago. The changes started with colonialism, and the prevailing mindsets of the invading strangers from Europe and newly “educated” Africans that our languages could be discarded without consequences. It was a gradual change, reinforced with every government policy, every textbook recommendation, every change in the educational syllabus, and every recommended dress code in government offices. Today, we are a people whose worldview is being conditioned and defined by competence in a new language, English, to the exclusion of our own.

Let me address an important irony: that which concerns the fact that I am presenting this talk in English and not in my own language. I have, after all, advocated that Nigeria’s president use his own language (Hausa/Fulfde) whenever he is out of the country. If I were the president of Nigeria in this instance, Yorùbá nìkan ni mo máa sọ. Aá fi sílẹ̀ fún àwọn ògbifọ̀ láti ṣàlàyé (I’ll be speaking only in Yorùbá, leaving it to the translators to explain). This is a suggestion borne out of my belief that the head of state represents the country and its multilingualism. His or her decision to speak the nation’s language outside shows a pride in the language and provides jobs for translators living in that foreign country while portraying a complexity of that country’s cultural landscape.

The irony comes because the purpose of my talk here is to advocate for a return to the local language use and support, and to explain why I believe that the poverty of imagination is equally as tragic as a poverty of the stomach. You, my hosts in Korea, don’t seem to have this dilemma. Your language is one (unless we discuss the widening gap that is happening between the version spoken here in the South, and that one spoken in the North). You don’t have too many dialects of the language, and citizens of this country do not have hundreds more competing for attention. But you are also lucky in another way. Even though English is spoken here as a second language, Korean still holds an important place as a vessel for the culture of the people. You can think in the language. You can conduct all your daily activities in it. It has a distinct writing style, and children are taught how to use it. And big technological giants care enough about it, and your buying power, that they carry it along with every new tool they create.

This is not the same for the languages in my country.

The problem, like I mentioned earlier originated in the over-simplistic tools we chose for dealing with diversity, and in colonialism. But it has also been carried along by an attitude of the population that rather than assert individual identity or spend valuable time developing each language through use in literature and other means of transmission, we might as well surrender and adopt English as the only “uniting” language. Don’t ask me how successful that drive for unity is. But the result is a gradual attrition of local languages. As at the last count, about twenty-seven languages in the country are either vulnerable, critically endangered, or severely endangered. It doesn’t look like the situation will improve anytime soon because unlike what obtained in the country a couple of decades ago, we no longer teach local languages in schools. The new students we produce from schools each year will only claim English as their first language. This doesn’t mean that they will be accepted abroad as first language speakers since the term “native speaker” is imbued with more than mere language competence, but with both political and cultural characteristics. I’ve spoken about this in other forums. This leaves us, Nigerians, and many other post-colonial outposts around the continent, at a terrible psychological, social, economic, and even political disadvantage.

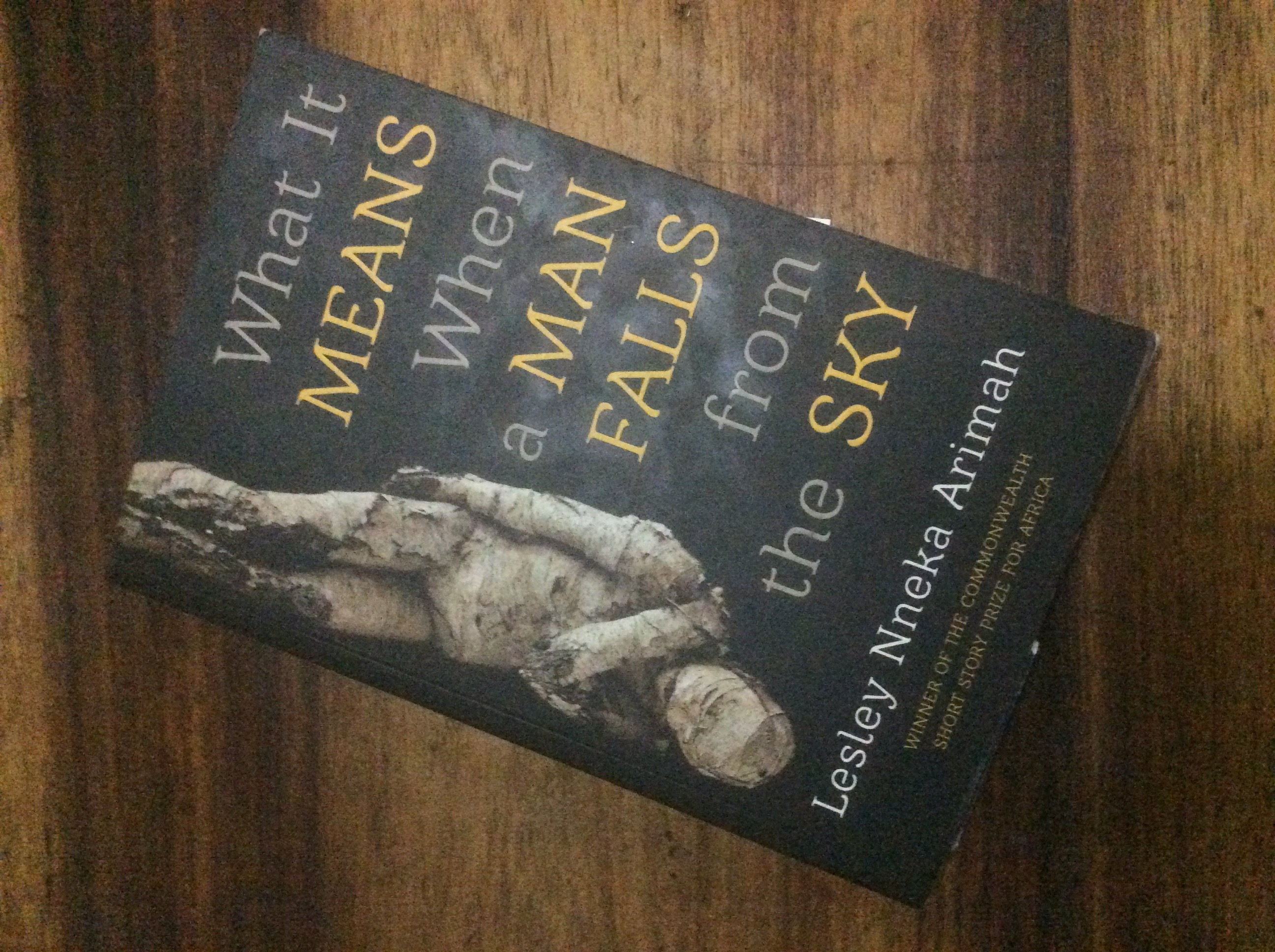

A more noticeable example of this kind of poverty comes with technology, which is my current focus as a writer and linguist. In some ways, it will be proper to look at the progress of today’s modern inventions through the lens of colonialism, carried into every part of the world on the back of convenience. From my part of the world, where we consume technology much more than we create it, a pattern has emerged. The new technological tools created to make life better for us are monolingual in nature. For an environment where thousands of languages are spoken, this is grossly deficient. And there’s no poverty as great as one that prevents a person from interrogating life in the language with which they are intimately familiar.

When I was in the university between 2000 and 2005, I used to wonder why Microsoft Word underlined my name with a red wriggly line whenever I typed it. But the answer was simple: Microsoft simply didn’t recognize a Yorùbá name. As long as the name wasn’t an English name, the red wriggly line showed you that something was wrong. So when I wrote my long essay, I did it on a project called a Multimedia Dictionary of Yorùbá Names. It was my way of introducing Yorùbá names to technology. Ten years later, I expanded the project to a fully functional and crowdsourced multimedia dictionary to which people can add new names, and improve current ones. And I did this not just for Yorùbá this time, but under the umbrella of what we called the African Language Project, we want to document all African languages and other intangible cultural materials like names, customs, norms, and words. As at this moment, there is no multimedia dictionary of Yorùbá on the internet. None that Africans can access on their phones at a moment’s notice. We are trying to create one. If more Africans who do not speak English at all, or as a first language, cannot interact with technology in their own language, then they are being left behind in the progress of technology. And that’s a powerful kind of poverty.

Around Nigeria today, there is barely any ATM machines that one can use in a local language. This means that people who only speak a local language will not put their money in banks, since the process of getting it out is onerous. Because of this, they are excluded from the big economy and thus remain poor. In a part of Northern Nigeria, poor farmers who need to work with modern implements have to first learn English before they can understand how to read the manuals. I know a couple of my friends who are working on artificial intelligence applications that can help these farmers communicate in Hausa and get access to all they need in a language they speak. But these efforts are far in-between. There’s a lot of work to be done, not just with widening the access that technology provides, but also in reading and producing literature, in engaging with participating in and discerning the details of our politics, and engaging with our everyday life. Like we say in Yorùbá, ọwọ́ ara ẹni la fi ń tún ìwà ara ẹni ṣe (“we have to use our own hands to fix our own issues”).

There are different kinds of poverty, all of them damaging to the dignity of man. A deprivation of language is one that is more pernicious than the rest because it deprives not just the body, but also the mind. The world is a colourful and delightful place to be in because of the multiplicity of languages and culture. I do not want to live in a world where only ONE language is spoken. That is a world that has lost its storehouses of wealth. We are all richer by the experiences we share from participating in each other’s cultures, language, worldview, and way of life. By working hard, and fighting hard in my own part of the world, to make sure that the movement of technology does not leave us behind in our own languages, we attack poverty, and build a new and exciting future that better reflects the mosaic; the colours, and the realities of the African – and our global – existence.

Thank you for listening. Kamsa hamida.