Press Release

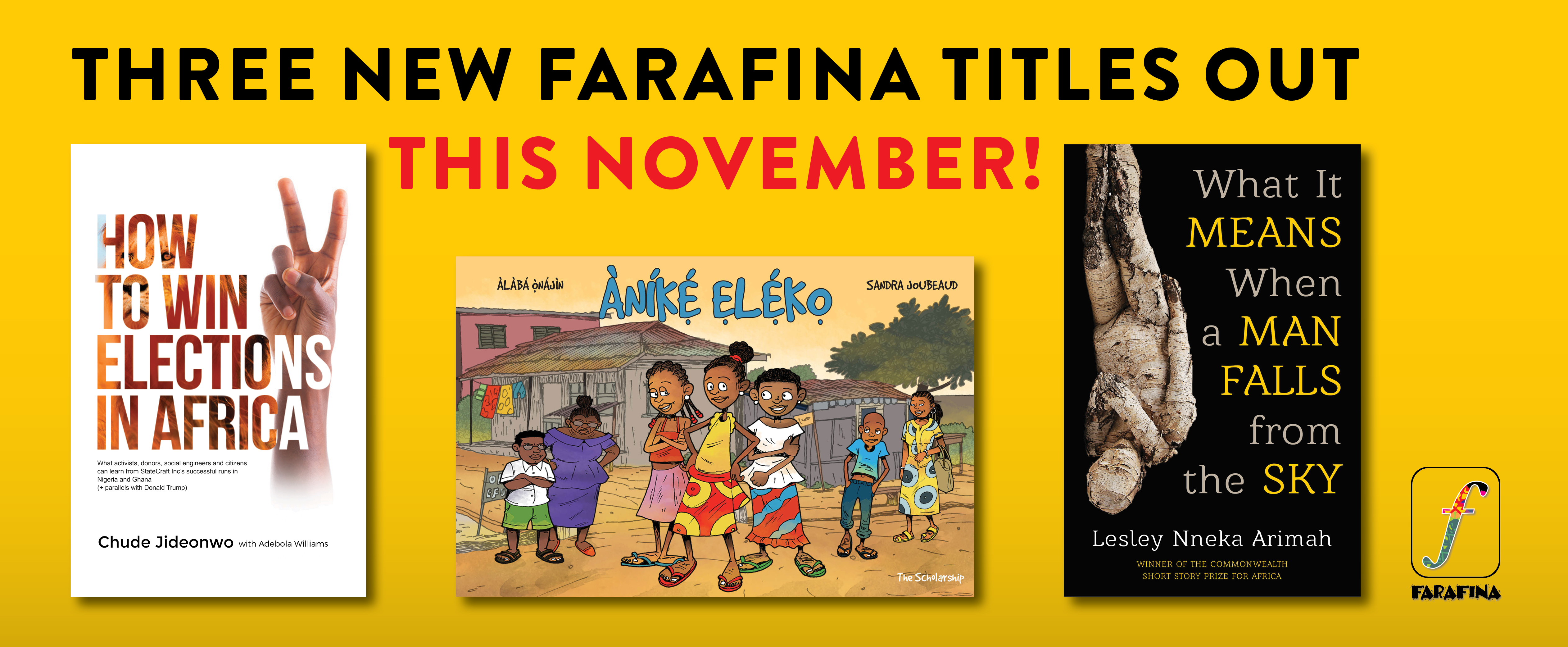

Kachifo Ltd is pleased to announce the release of three new books – What It Means When A Man Falls From The Sky (Nigerian edition), How to Win Elections in Africa and Àníkẹ́ Ẹlẹ́kọ under its Farafina, Kamsi and Tuuti imprints.

The three titles were released on 13th November 2017 and are available on online platforms and in selected bookstores nationwide.

The Books

WHAT IT MEANS WHEN A MAN FALLS FROM THE SKY by Lesley Nneka Arimah

The collection of short stories, which was shortlisted for the 2017 Caine Prize for writing, boasts of powerful storytelling, unique female protagonists, and a world where women are depicted as the center of the society.

Reviews:

From Tendai Huchu, author of The Hairdresser of Harare, and The Maestro, The Magistrate & The Mathematician:

“Arimah has a gift of crafting intimate familial relationships . . . and the pressures and strains of those relationships form the most intricate and astonishing narratives. The powerful stories in this dark and affecting collection will show you that magic still exists in our world.”

From Chinelo Onwualu, editor of Omenana Magazine: “Masterfully moving between the speculative to the mundane, this is a riveting read that will stay with you long after you’ve put it down.”

From Igoni A. Barrett, author of Blackass and Love Is Power, or Something Like That:

“From the very first story in What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky this thunderstruck reader began to glean the answer to the question embedded in the book’s title. . . Lesley Nneka Arimah has landed in my rereading list like a blast of fresh air.”

About the Author

Lesley Nneka Arimah’s work has received grants and awards from Commonwealth Writers, AWP, the Elizabeth George Foundation, the Jerome Foundation and others. Her short story, What It Means When A Man Falls From The Sky was shortlisted for the 2017 Caine Prize for African Writing. She currently lives in Minneapolis.

ÀNÍKẸ́ ẸLẸ́KỌ

Àníké has to hawk ẹ̀kọ every morning but that does not stop her from going to school. She loves school and wants to be a doctor. However, her mother has decided her fate: once she finishes primary school, she will join her Aunt Rẹ̀mí in the city as a tailor.

When a mystery guest visits Àníké’s school, she has the chance to win a scholarship that will change her fate. Will the help of her friends Oge, Ìlérí and Àríyọ̀ the cobbler be enough?

Written by Sandra Joubeaud and illustrated by Àlàbá Ònájìn, ÀNÍKÉ ELÉKO tells a colourful story of one girl’s courage in the face of opposition to her dreams.

About the Authors

Sandra Joubeaud is a French screenwriter and script doctor based in Paris, France. She has also worked on Choice of Ndeye, a comic book commissioned by UNESCO and inspired by the novel, So Long a Letter (Mariama Ba).

Àlàbá Ọ̀nájìn is a graphic novelist with a diploma of Cartooning and Illustration from Morris College of Journalism, Surrey Kent. His work includes The Adventures of Atioro, and other collaboration projects with UNESCO and Goethe Institut. He lives in Ondo State, Nigeria.

HOW TO WIN ELECTIONS IN AFRICA

Democracy involves the process of changing custodians of power from time to time in order to maintain a useful equilibrium of performance and accountability. But the post-colonial narrative in most African countries has been one of the strongmen and power brokers entrenching themselves deeply across the crucial levels of society. The past few years have however seen citizens become more aware, and some revolt against these systems.

How To Win Elections in Africa explores how citizens, through elections can uproot the power structures. Using examples from within and outside Africa, this book examines the past and present to map a future where the political playing field is level and citizens can rewrite existing narratives.

Politicians have been handed their notice: It is no longer business as usual.

About the Authors

Chude Jideonwo is the managing partner of RED, which brands include StateCraft Inc, Red Media Africa, Y!/YNaija.com and Church Culture. His work focuses on social movements shaking up and transforming nations through governance and faith, with the media as a tool. He teaches media and communication at the Pan-Atlantic University. In 2017, he was selected as a World Fellow at Yale University.

Adébọ́lá Williams is the co-founder of RED and chief executive officer of its communication companies – Red Media Africa and StateCraft Inc. A Mandela Washington Fellow under President Barack Obama, he has been a keynote and panel speaker at conferences across the world including at the London Business School, Wharton, Stern, Yale, Columbia, Oxford and Harvard.