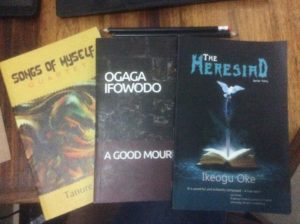

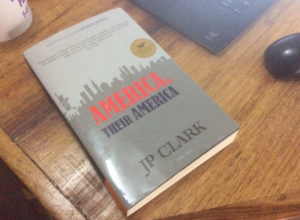

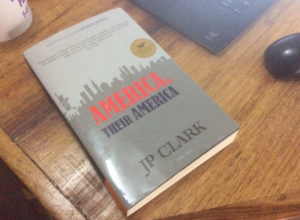

It’s amazing to think that an African writer/journalist had the kind of access that Nigerian writer JP Clark had to the corridors of US power in 1962 during the Medicare debates, and some of the most high-stakes political period of the country’s history. The writer, then a playwright and journalist working in Nigeria, had won a Parvin Fellowship which, at the time, had been set up to bring young African professionals to the US for one year in order to interact, socialize, learn a bit about the American political system, and gain some skills to take back to their young countries. The result of that experience, and the subsequent fallout from his abrupt ejection from the country, was his 1964 book America Their America now re-published in a 50th anniversary edition by Bookcraft, Ìbàdàn (2015).

At that time in the 60s, all of the countries on this continent had either just gained independence or were in the process of doing so. The coup d’etat hadn’t started rolling in (as they did in Ghana and Nigeria in 1966). The CIA hadn’t started getting too involved in the political process of new states that turned away from the western-type ideals enough to start helping to assassinate them. Names like Wọlé Ṣóyínká had not become household names yet, and Chinua Achebe himself was still in the United States on a different study programme. In short, it was the golden years of statehood of many African countries on the world stage, and this benefited students from the continent who took adequate advantage of America’s attempt at a global outreach through soft diplomacy. It was also during this time that Barack Obama Sr had found himself in Hawaii as a father of a new American son, Barack.

At that time in the 60s, all of the countries on this continent had either just gained independence or were in the process of doing so. The coup d’etat hadn’t started rolling in (as they did in Ghana and Nigeria in 1966). The CIA hadn’t started getting too involved in the political process of new states that turned away from the western-type ideals enough to start helping to assassinate them. Names like Wọlé Ṣóyínká had not become household names yet, and Chinua Achebe himself was still in the United States on a different study programme. In short, it was the golden years of statehood of many African countries on the world stage, and this benefited students from the continent who took adequate advantage of America’s attempt at a global outreach through soft diplomacy. It was also during this time that Barack Obama Sr had found himself in Hawaii as a father of a new American son, Barack.

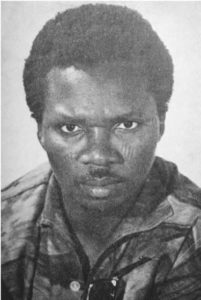

And there was JP Clark, a young and boisterous playwright and journalist from Nigeria with, not unlike what has been described of Obama Sr, an acerbic voice, a confident gait, and a snarky outlook at the elaborately choreographed introduction to the American experience, which the Parvin Program had packaged for him. Even in his own accounting of the times, he was a rude, and unfiltered guest, willing to poke where the society he found himself had decided needed to be left alone: religion, politics, and race. He spent most of his time pursuing his own creative and personal haunts than spending time participating in the rituals required of the scholarship that had brought him to the United States, and he did these all while throwing his weight and sometimes solicited opinion around, often to devastating personal consequences. In the end, his host had had enough, so they kicked him out rather unceremoniously.

The country had, until then, seemed never had such a caustic guest. It certainly had not expected it from this African, half expected to be grateful and obsequious for the privilege that the opportunity had brought, and certainly expected to take the opportunity as one that may never come again. They, apparently, hadn’t met Mr. Clark, the saucy poet, who traipsed around America among some of the most influential members of that country’s society, in culture, academia, literature, and government not quite like he owned it, but like his critical opinion should matter as much as any man, intellectual, and journalist of his competence. And why not? Was he less of a journalist because he carried a green passport or a black African skin? Is America, a country founded ostensibly on the freedom of speech, not naturally best suited for, and welcoming to critical engagement by all that live in it towards “a more perfect union”? At the time, it certainly didn’t seem that any negative or uncomfortably frank perception or opinion was expected of this stranger, and he was informed of this, subtly and directly. He didn’t care. And, today, it is in that quality of brutal honesty and self-indictment that the book America Their America earns its stripe as a cultural landmark – a work of both political, journalistic, cultural, and literary value, packing an unapologetic look at the American political and cultural landscape with an attentive recollection of one man’s travels and travails through its corridors at a crucial time.

JP Clark (Author’s photo from the 60s)

I had moments of deja vu, while reading America Their America, not just because of the eerie similarity of those times and the depicted political realities and the current one, but also because of the similarity and dissimilarity of the visiting experience of Mr. Clark and myself. He had been invited into the country as a Parvin Fellow (a fellowship that was discontinued a few years later, perhaps no thanks to his fiery and bold-faced ungratefulness for much of the fellowship except for parts of it that allowed him the freedom to travel and experience America on his own terms) and I had made my first contact with America as a Fulbright Scholar in 2009 on similar terms. Except in the location of my fellowship and the teaching responsibilities expected of Fulbright fellows, we seemed to have been invited to experience the country in much the same way, through its generosity and openness to exchange of new ideas, and packaged through a rote of American perception of itself as exceptional.

Reading America again through his eyes brought moments of intense recollection, sometimes of nostalgia, but mostly of envy for the kind of access the Parvin Fellowship offered the writer and other fellow scholars. I certainly never got a chance to visit the Capitol building in order to watch legislative deliberations or have 0ne-on-one conversations with congress people. I did walk in front of it, but only because of my own restlessness. Neither, except for my own equally deliberate and constant rebellion against the constraints of a regimented school session, did I experience a year of such intense and colourful freedom. But it is the literary and historical value of the book that packs the most punch for an interested reader as myself committed as much to its contribution to understanding the 60s and early black scholars in and out of the West and the trajectory of the early African writers’ literary voice. Mr. Clark delights both as an astute storyteller of a tale in which he’s both the hero and the villain, and a travel writer experiencing reality through a fiery literary lens.

He complements the narrative with occasional poems written at moments of distress or contemplation. This one was written while thinking of James Meredith (the first African American to attend the University of Mississippi) and composing a letter to his brother in India:

Last night, times out of dream,

I woke

to the sight of a snake

Slitering in the field, livid

Where the grass is

Patched, merged up where it runs

All shades of green – and suddenly!

My brother in India, up, stick

In hand, poised to strike –

But ah, hiimself is struck

By this serpent, so swift,

So silent, with more reaction

Than a nuclear charge…

And now this morning with eyes still

To the door, in thought of a neck

Straining under the sill,

I wake

To the touch of a hand as

Mortal and fair, asking

To be kissed, and a return

To bed, my brothers

In the wild of America!

(page 56)

Of Washington DC, he wrote, a terse indictment:

A morgue,

a museum –

Whose keepers

play at kings.

(page 184)

In each poetic offering on the state of his mind at different moments, one glimpsed doses of frustration, mirth, mischief, inspiration, and more. It was a peek into the creative potential of the – at the time – 29 year-old author. The style, in which poetry and prose were effectively deployed to serve the purpose of memorizing, would also be deployed equally as effectively in Wọlé Ṣóyínká’s The Man Died (1971).

Politically, what impressed and fascinated me, even more, is the relevance of the debates that JP Clark diligently documented of the Senate debates surrounding the passage of the Medicare Act of 1965, and how little seemed to have changed. As I write this, the US Senate has just given up on their latest attempt to repeal the healthcare law signed into effect in 2009, a law that takes care of the most vulnerable in the society just like Medicare did in 1965. And watching the US media debates surrounding healthcare as I had when I lived in Illinois in 2009-2012, the following passage seemed very familiar:

“How are you sure he wants to follow in his father’s footsteps?” I asked.

“He darned well will want to,” the man said. “Why, he’ll all be provided for. I have built this business up for what it is today so no member of my family will lack for anything.” And here he brought out another photograph, this time of the entire family, even with the old parents included. Radiant in the centre with a strapping son and two daughters on her either side was his wife.

“Now, they’re pretty well taken care of, for now and the future as far as human hand can provide.” He congratulated himself and the American system of which he was a shining ‘success’ example.

“Don’t you think by all this provision and security, you deny them their great American privilege of paying their own way through life?” I asked.

“How is that? he showed genuine surprise and disbelief.

“Well, I can appreciate the point of your doctors when they say they want no medicare for the old,” I began.

“Go on,” he prompted me, calling out for more drinks for us both in the bar where we sat.

“As I see it, the doctors seem to be insisting that every American citizen should have provided for himself fully by retirement age. So why ask government now to pay their full medical bills?”

“That’s right, boy, you’ve been following pretty close our American debate,” he cheered me on. Until I added:

“Well, it seems to me you’re denying exactly that sacred principle the doctors are insisting on by wanting to lay on everything for members of your family.”

“Young man, are you calling all my life’s effort vain? No, no, don’t withdraw or make any apologies for beliefs you honestly hold to. But tell me, as a writer, of what I don’t know, don’t you want to make money?”

(page 182-183)

As a Parvin Fellow, Mr. Clark was based in Princeton, but the traveller’s gene in the poet carried him around the country, from New York to Boston, and to DC. As a Fulbright fellow, I resided in Southern Illinois, with aspects of my work taking me to Rhode Island and Washington DC. But much of my emotional connection to Mr. Clark’s delightfully addictive rant against his uncomfortable participation in American life comes also from my hitherto lack of sufficient time and discipline to put my one-year experience into the words and images, with diligent markings of its most notable moments, as the writer has brilliantly done. America Their America was published about a year after the writer had returned unceremoniously after being kicked out of the fellowship for failing to show up in class. The closeness of that recollection to the space and time of the event’s happenstance probably helped its acerbity. But its ability to endure, even till today, as one of the most honest accounts of an African writer’s sojourn in America is tribute to the writer’s impressive talent, creative fire, and artistic integrity.

Another part of the book caught my eye:

Americans, very true to their candidatural role, like being liked a lot by foreigners. The picture they cut is of a big shaggy dog charging up to the chance caller in mixed feelings of welcome and defiance, and romping one moment up your front with its great weight, all in a plea to be fondled, and in the next breaking off the embrace to canter about you, head chasing after tail, and snout in the air, offering furious barks and bites. “Where are you from?” they breathe hot over the stranger to their shores. And before you have had time to reply, they are pumping and priming you more: “How do you like the US? Do you plan to go back to that country? Don’t you find it most free here? In Russia the individual is not free, you know, he cannot even worship God as he likes and make all the money he should.” And from this torrential downpour of self-praise the American never allows the overwhelmed visitor any cover, actually expecting in return more praise and a complete instant endorsement. God save the brash impolitic stranger who does not!

Little wonder why his visit ended with such infamy!

But such a shame that the fallout from the perception of his “ungratefulness” for writing the book had coloured the author’s subsequent negative perception among Western gatekeepers of African literature from which he never recovered. Heck, it had coloured perception on the continent itself, allowing publishers (many of which had ownership in the West anyway) to distance themselves from it. The book, for all of fifty years, remained invisible on bookshelves, earning its reputation only by word-of-mouth while other memoirs that came after it (The Man Died; 1971, Second Class Citizen; 1974) had enjoyed multiple print runs. Hard to think of any other book of such fame/infamy not having a second reprint for fifty years.

“Out of Print-Limited Availability” on Amazon today.

“Out of Print-Limited Availability” on Amazon today.Yet even if we ignore the much more fruitful contribution of the author to the African literary space, the service that the presence of a book of this nature offers continues to be relevant, not just for African writers, many of whom have found less assertive ways of navigating the American immigrant experience either through soft engagement (see: Americanah, Open City, Never Look an American In the Eye), or through silence (see: Ngugi, Achebe, Soyinka), but for writers in general and for people interested in the enduring power of documentation with honesty and verve. JP Clark won’t be with us forever, but many of the issues raised by the book continue to be a relevant mirror to the American society, just as valid as those by its own active citizens, from James Baldwin to Ta-Nehisi Coates.

To call it merely an “African” classic is to do it too much disservice. It’s a classic nevertheless.

—-

(Rating 5/5)