When I lived in Ibadan, there was these jazz sessions at Premier Hotel which took place every weekend (can’t remember now if it was Friday or Sunday nights). It held in a ballroom on the ground floor of the hotel and featured an ensemble that played non-stop for about four hours, late into the night. The music swayed from highlife to jazz, and sometimes to juju, but always within a range of danceability. Guests who sat around the stage in different arrangements often got up from their tables to dance, alone or with their guests. There was always food and drinks.

Sponsored message: Before you plan your trip, check out Hotels.com voucher codes to find out what deals enables you to save on your reservations. It is always good to have prior reservations done to avoid sky-scraping prices later.

I attended a couple of those sessions while I was a student, with friends and colleagues from the university. It always provided a kind of relaxing end to the week. We had nice stimulating conversations, got our fill of good music and food, and exercised the stress away. The location, on top of the hill at Mọ́kọ́lá, also provided not just a beautiful overview of Ìbàdàn at night, but also a very relaxing access to cool breeze. By morning, one felt refreshed and ready to take on the next week.

I attended a couple of those sessions while I was a student, with friends and colleagues from the university. It always provided a kind of relaxing end to the week. We had nice stimulating conversations, got our fill of good music and food, and exercised the stress away. The location, on top of the hill at Mọ́kọ́lá, also provided not just a beautiful overview of Ìbàdàn at night, but also a very relaxing access to cool breeze. By morning, one felt refreshed and ready to take on the next week.

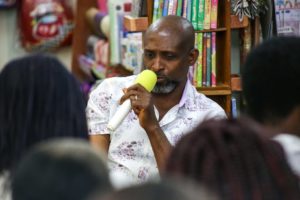

Yesterday, I had an experience very close to that, which brought the memories back. It was at 16 Kòfó Àbáyọ̀mí Street, Lagos, on the eighth floor of a building I never knew existed there, with a relaxing view of the Lagos Lagoon, and a high-up-enough location to soothe a most exhausted traveller. The event was Títílọpẹ́ Ṣónúgà’s poetry concert event titled “Open”. Gate fee: 5000 naira. It is the first of a three-part performance show slated around venues in Lagos.

I don’t know if “concert” is the right word, because the poet approached it like a soulful conversation between an artist and her audience. But the word still closely captures some of the show’s best aspiration. In a space that felt intimate because of its size, the lighting, and the mood, an artist performed to an audience, and the result was delightful.

I haven’t been to many spoken word concerts. My contacts have been limited to more public spaces like the halls of the June 12 Cultural Center in Abẹ́òkuta where poets from all around the world have performed to a much larger audience during the annual Aké Festival, and to YouTube channels and TED Talk videos, where poets with verve, rhyme, and sass have dazzled with inspirational and stimulating turns of phrase and soulful rendition of their work. There are a few other avenues that have popped up over the years though. I know, at least of Taruwa, which (I believe) featured open mic events for amateur and established spoken word artists to come impress an audience. But this one felt different, perhaps because it also included an element of music necessary to move even the most inexorable skeptic of the beauty or relevance of poetry in performance.

I haven’t been to many spoken word concerts. My contacts have been limited to more public spaces like the halls of the June 12 Cultural Center in Abẹ́òkuta where poets from all around the world have performed to a much larger audience during the annual Aké Festival, and to YouTube channels and TED Talk videos, where poets with verve, rhyme, and sass have dazzled with inspirational and stimulating turns of phrase and soulful rendition of their work. There are a few other avenues that have popped up over the years though. I know, at least of Taruwa, which (I believe) featured open mic events for amateur and established spoken word artists to come impress an audience. But this one felt different, perhaps because it also included an element of music necessary to move even the most inexorable skeptic of the beauty or relevance of poetry in performance.

Accompanying Ms. Ṣónúgà last night was a bass guitarist, a pianist, and a man on the drums, along with a certain Naomi Mac whose voice carried the soulfulness demanded of the intimate occasion with ease and grace. With their accompaniment, the show was fully realized not just as a celebration of the power of the word or Ms. Ṣónúga’s poetic capabilities but as a ritual of mass catharsis; an artistic triumph.

Accompanying Ms. Ṣónúgà last night was a bass guitarist, a pianist, and a man on the drums, along with a certain Naomi Mac whose voice carried the soulfulness demanded of the intimate occasion with ease and grace. With their accompaniment, the show was fully realized not just as a celebration of the power of the word or Ms. Ṣónúga’s poetic capabilities but as a ritual of mass catharsis; an artistic triumph.

The poems performed came from some of Títílọpẹ́’s recent works, a few of which I’d read on other platforms or heard in other places. Perhaps it was deliberate, a way to get the works performed again in a perfect setting of her choice, recorded along with the audience reactions. Some I was hearing for the first time. What united them was the theme of the evening: an openness to possibilities, in love, in life, and in public engagements. Navigating the tale of personal heartbreak, the process of finding love, coming of age, political instability, societal dysfunction, naivete, lust, love, and consent, the poet details her personal artistic response in a voice and style that is as open as it is reserved. (In a notable poem about a seeming first sexual encounter, for instance, the poem ends “he knows the punchline to this joke, and I’ll never tell“).

In the end, it was as much a beautiful intimate gathering as it was a much needed artistic intervention in a city space much in need of a lot more events of this character. We need plenty more.

_____

More about the last two performances here. Títílọpẹ’s earlier work “Becoming” was reviewed here. Photos 1 and 2 from Titilope Sonuga’s Instagram page.

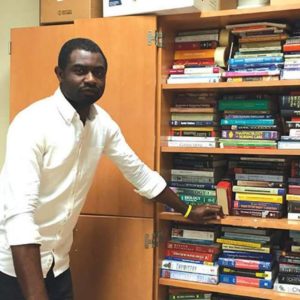

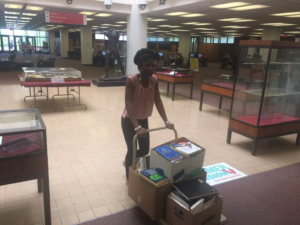

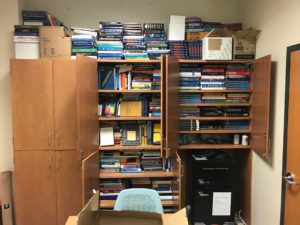

When Àlàbí first arrived in the U.S. two years ago to begin his master’s of science degree in chemistry at SIUE, he saw first-hand how relatively affordable university-level textbooks are to acquire in the U.S. compared to Nigeria. He also saw stacks of still-relevant textbooks in good condition that were being discarded.

When Àlàbí first arrived in the U.S. two years ago to begin his master’s of science degree in chemistry at SIUE, he saw first-hand how relatively affordable university-level textbooks are to acquire in the U.S. compared to Nigeria. He also saw stacks of still-relevant textbooks in good condition that were being discarded. “We thought maybe we’d receive a couple hundred donated textbooks at our initial book drop-off sites on campus at SIUE,” said Àlàbí, who will pursue a doctoral degree in chemistry from Brown University in August. “That initial donation topped 1,000 textbooks in only a few months. We also raised funds to pay for the cost of transporting the books by ship to my home university, Tai Solarin University of Education in Nigeria. We are absolutely confident that we can continue the momentum and tap into the generosity of teachers and learners in the U.S.”

“We thought maybe we’d receive a couple hundred donated textbooks at our initial book drop-off sites on campus at SIUE,” said Àlàbí, who will pursue a doctoral degree in chemistry from Brown University in August. “That initial donation topped 1,000 textbooks in only a few months. We also raised funds to pay for the cost of transporting the books by ship to my home university, Tai Solarin University of Education in Nigeria. We are absolutely confident that we can continue the momentum and tap into the generosity of teachers and learners in the U.S.” “We encourage individuals and student associations at community colleges, technical colleges and universities across the Midwestern states who are willing to designate a location on their campus as an Efiwe textbook drop-off site,” Àlàbí said.

“We encourage individuals and student associations at community colleges, technical colleges and universities across the Midwestern states who are willing to designate a location on their campus as an Efiwe textbook drop-off site,” Àlàbí said.  Over 500 languages are spoken in Nigeria today, according to most accounts, although many of them are dying, endangered, or extinct. Three major languages spoken more widely than others are Hausa in the north (with about 70 million speakers), Igbo in the east (with about 24 million), and Yorùbá in the west (with about 40 million speakers). Other languages include Edo, Fulfude, Berom, Efik, Ibibio, Isoko, etc. Because of the multiplicity of languages in the country and the need to communicate among different ethnic groups, English, or Nigerian English, has served as a connecting tissue, but only in formal circles: schools, government, courts, etc. In the informal sector, however, where most Nigerians function every day, in the markets, on the streets, at restaurants, Nigerian Pidgin (NP) has emerged as a crucial and important feature.

Over 500 languages are spoken in Nigeria today, according to most accounts, although many of them are dying, endangered, or extinct. Three major languages spoken more widely than others are Hausa in the north (with about 70 million speakers), Igbo in the east (with about 24 million), and Yorùbá in the west (with about 40 million speakers). Other languages include Edo, Fulfude, Berom, Efik, Ibibio, Isoko, etc. Because of the multiplicity of languages in the country and the need to communicate among different ethnic groups, English, or Nigerian English, has served as a connecting tissue, but only in formal circles: schools, government, courts, etc. In the informal sector, however, where most Nigerians function every day, in the markets, on the streets, at restaurants, Nigerian Pidgin (NP) has emerged as a crucial and important feature.