The first time I met Buchi Emecheta in person was in 2005, just after my debut novel Everything Good Will Come was published. I had contacted her through an old college mate, Kadija George, to ask for an endorsement, which she very kindly agreed to give. To paraphrase her endorsement, she wrote that reading my novel was like listening to an old friend talk about Lagos.

That was the same year she was awarded an OBE for her contribution to literature, and Kadija organised a celebratory dinner at a Caribbean restaurant in North London, to which I was invited. At the restaurant, she signed a copy of her book Head Above Water for me, with a message: “To Sefi, good luck with your publication, love from Auntie Buchi”. I read an excerpt from the book at today’s memorial event, not just because it’s autographed, but because it’s a testimony of what it means to be a writing mother, and because it’s good storytelling: entertaining and informative, guileless and revealing, intimate, and rendered in the meandering fashion of Igbo oral history, which, by the way, bears some resemblance to that of the American South, where I’m based most of the year.

That was the same year she was awarded an OBE for her contribution to literature, and Kadija organised a celebratory dinner at a Caribbean restaurant in North London, to which I was invited. At the restaurant, she signed a copy of her book Head Above Water for me, with a message: “To Sefi, good luck with your publication, love from Auntie Buchi”. I read an excerpt from the book at today’s memorial event, not just because it’s autographed, but because it’s a testimony of what it means to be a writing mother, and because it’s good storytelling: entertaining and informative, guileless and revealing, intimate, and rendered in the meandering fashion of Igbo oral history, which, by the way, bears some resemblance to that of the American South, where I’m based most of the year.

Anyway, that evening at the restaurant, I found Buchi Emecheta pensive. I imagined she was aware of her achievements and was proud of them: all the novels, plays and children’s books she’d written, the family she had raised, and the obstacles she’d had to overcome. People often mention the burning of her first manuscript, but the daily grind of being a mother to young children, while getting a university degree and writing, was hard enough.

I know this. I have one child, a daughter, much beloved, but I didn’t think I would be capable of giving her the attention she deserved if I had more. I was thirty-three when I started writing full time and she was three. I was working on Everything Good Will Come and had more stories to tell. I wanted to go back to school to get a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing. My husband, Gbóyèga Ransome-Kútì, a doctor, got a job in Mississippi, of all places, and we had just moved there. Before the move, I had worked as a Chartered Accountant and Certified Public Accountant. Following the move, I was not legally allowed to work in the United States until I had found an employer to sponsor my work visa. I was in two minds about living in Mississippi but Gbóyèga quite liked his job. He was supportive of my writing, to the extent that he would cook while I wrote, and thankfully, on the issue of children, we were both on the same page.

Buchi Emecheta often said she saw her books as children. I don’t look at mine that way. My daughter is my child, and my books are my work, though the time I spent writing them did take away from time I could have spent with her. She is graduating from college this year, after a four-year degree. At twenty-two, she is the same age Buchi Emecheta was when she had five children and was studying sociology at London University, and writing. So, to me, Buchi Emecheta was a child bride, child mother and child divorcee, who would later become a renowned writer published in journals such as Granta and the New Statesman, with television scripts produced by the BBC and Granada. And even though one of my first interviews in Nigeria, as a published writer, was titled “Sefi Atta following in the footsteps of Buchi Emecheta”, or something to that effect, my path has been quite different from hers. However, like most Nigerian women writers, we’ve had similar preoccupations with girlhood, womanhood and motherhood, with marriage and religion. For some of us, I would add the death of relatives and the state of being African overseas.

When Buchi Emecheta writes about missing her late father, so I have missed mine. When she writes about her children walking around in wet nappies, I admit, I was sometimes too busy writing to notice my daughter’s diapers needed to be changed. When she writes about racist or xenophobic employers and colleagues in London, I remember my experiences as an accountant in London and New York. She recounts details of difficult relationships with editors and agents; I can recall one or two. She takes a swipe at Enoch Powell; I immediately think of Trump.

What I find most interesting about her works are the paradoxes – of forging ahead from one generation to the next, yet returning to old positions; of her ability to be naïve and insightful at the same time. And judging from her autobiography, what sets her apart from most Nigerian women writers of her time, and mine, is that she was incredibly resourceful, industrious and tenacious. For a self-described small woman, Buchi Emecheta had enormous strength. She could also be stubborn. In Head Above Water, she tells us how she constantly defied people who tried to patronise or diminish her, and how she was reluctant to be labelled by anyone, feminists included. In a book titled In Their Own Voices, a collection of interviews with African women writers, edited by Adeola James, she expressed her frustration about feminists she encountered in the West, who took centre stage at conferences and overlooked her views.

Twelve years ago, when I met her, feminism was a lot more unpopular than it is now, and although I proudly called myself a feminist back then, whenever I was asked, I was reluctant to be labelled a feminist writer because my stories weren’t always in line with feminist narratives. Besides, if you’ve experienced conflicts solely because you’re a girl or a woman, and you write about them, that doesn’t mean you’re a feminist. It just means you’re female.

I was forty-one when I met Buchi Emecheta. I’m fifty-three now. These days, feminism is more mainstream, and commodified, and celebrity-driven. In fact, if you’re an actress announcing your next film, or a singer releasing your latest album, it helps to declare that you’re a feminist, even if you might face some backlash.

I must confess that although I still call myself a feminist whenever I’m asked, I’ve never seriously studied feminist thought. I’ve read about notable feminists like Simone de Beauvoir and Germaine Greer. I’ve read bell hooks’ works because they appeal to me and speak to my experience in America. I’ve also read academic books on Nigerian and African women writers, but that’s about it. Now, I have met, online and in person, Nigerian academics who have written about feminism, such as Mọlará Ògúndípẹ̀-Leslie, Amina Mama and Oyèrónkẹ́ Oyèyẹmí, but I am yet to read their works, or any scholarly works that address the penkelemesis – the peculiar messes – that Nigerian women find themselves in. I think it is necessary to educate yourself on feminist ideas, and to live up to feminist ideals, if you call yourself a feminist; otherwise, it’s rather like saying you’re a born-again Christian. Every other Christian in Nigeria is born-again. They’re usually versed in the Bible, I’ll give them that – though I might quarrel with their interpretations of it and question whether they live up to Christian ideals. I mention Christianity not to be perverse. It was a foreign imposition we now readily embrace, so maybe there’s hope for feminism.

Like Buchi Emecheta, I don’t want to be labelled by any word that excludes my experiences, and, to be honest, I no longer think it’s necessary to call a woman a feminist simply because she has common sense and uses it. When you expect and demand equality and fairness, that’s all you’re doing: using your common sense.

But I digress. The point is, Buchi Emecheta’s works were my introduction to Nigerian feminist ideas. I understood her ambivalence about Western feminism and welcomed her calls for unity amongst women. In Head Above Water, she expressed her disappointment at women who resented her whenever she made progress. To piggyback off bell hooks’ term, in a tribalistic capitalist patriarchal culture like ours, women who claim to be pro-women are not always pro women they regard as competition. It’s the same between men, except they don’t profess to be pro-men. They just are.

Buchi Emecheta didn’t seem to regard other Nigerian women writers as threats to her success. Flora Nwapa, in In Their Own Voices, referred to her as a friend. On a separate note, she didn’t appear to be prejudiced against Nigerians of other ethnic groups, either. Her works suggest she honoured Igbo culture without idealising it, and opposed tribalism even after she faced it. She apparently responded to racism the same way, which I don’t understand. It takes a lot of grace to resist retaliating to prejudice. I’m still working on it.

For me, reading Buchi Emecheta is like listening to an aunt, a busy aunt who makes time to tell you her story. You almost hear her saying, “This happened and then this happened. Wait, wait. I haven’t finished. Don’t cry for me. Don’t get angry yet. Listen to what I have to say and learn from it.” You take your cue from her on how to react. There were sections in Head Above Water where I was sad for her, but she lightened them with humour. There were other sections in which I was angry on her behalf, but she didn’t allow my anger to last. It wasn’t until I reached the end of the book that my emotions overwhelmed me. But, according to her, that was how she coped with hers. She didn’t have time to dwell on them.

In fact, Buchi Emecheta is – and I use the word “is” deliberately: I often talk about deceased writers as if they’re still alive – she is the aunt in your family who stands out. The one who has done something to offend the sensibility of others, and when you find out what it is, you wonder what the fuss is about because she was just being herself, or speaking her mind. She’s really not a troublemaker. She might even be shy and insecure, as Buchi Emecheta says she was. But if you cross her path and she’s fed up with playing nice . . .

You observe her in action. You occasionally worry about her. Then, one day, she’s no longer around and you realise what she meant to you. The options she gave you. But it’s too late to tell her how much you admired her.

Last year, I emailed Kadija to ask if she could put me in contact with Buchi Emecheta again. I wanted to use a quote from her novel The Joys of Motherhood in one of my own, Made in Nigeria. My novel has a section in which a Nigerian professor teaches Joys, and Ama Ata Aidoo’s Our Sister Killjoy, to Mississippi college students, as I had done. Kadija got in touch with Buchi Emecheta’s son, Sylvester Onwordi. I had no idea whether she herself was approached, but I was given the permission I needed.

Afterwards, I have to admit that, for a moment, I hoped she would be around when the novel was published. I was afraid she might not be. I hadn’t seen her since we met at the restaurant. I reach out to writers I admire for professional reasons. I’m not one to cosy up to them. I prefer to respect their privacy and space. I’d heard she had some health challenges, but I didn’t want to pry.

Then in January this year, Kadija sent me the email saying she had died, and I was sad, partly because we no longer had an opportunity to celebrate her in person. It was our responsibility to do so and our loss that we didn’t. When we fail to honour our literary heroines, or stop honouring them, we lose as a group. As Nigerian mothers would say to children who don’t listen, “You are not doing anyone but yourself.”

Buchi Emecheta’s work is done and will continue to resonate. She has plenty of admirers in readers and writers who choose to walk their own paths. Her biography demonstrates that the most powerful thing a woman writer can do, regardless of what is going on, is to keep speaking her mind and producing work for as long as she possibly can.

She did just that, and in doing so, exposed the tribe, unashamedly, to strangers, which probably displeased some of our literary heroes, who at the time were more concerned with attacking imperialism, colonialism, military regimes and corrupt governments. She may also have offended the strangers themselves, by putting them in their place face to face and revealing what she thought about them in her books. But you don’t get the impression that her intention was to offend. Instead you get the impression she was merely trying to take control of her own story, the narrative of her life, and write her way out of her lot. However, if traditional Igbo beliefs on fate are correct, perhaps all she could do was give it her best attempt and leave it up to younger writers to carry on her legacy.

I am one of them. At the age of thirty-three, with a three-year-old child and two professional qualifications in accountancy, I found myself in Mississippi, without a job, and wrote my way out. I didn’t know Buchi Emecheta well personally. I learnt about her through her works. I appreciate the example she set by being prolific, her individuality and honesty. Perhaps I’ve got the wrong idea about her, and I still don’t know if she was aware I’d asked to use a quote from her novel, but of my final statement I have no doubt. I am glad I wrote about her novel in mine.

_____

An abridged version of this write-up was read at the Tribute to Buchi Emecheta which held at Terra Kulture on Saturday, March 25, 2017

_____

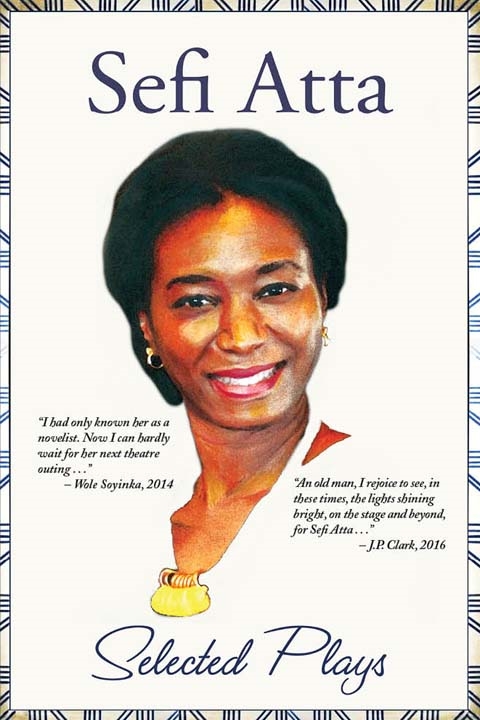

SEFI ATTA was born in Lagos, Nigeria, in 1964 and currently divides her time between the United States, England and Nigeria. She qualified as a Chartered Accountant in England, a Certified Public Accountant in the United States, and holds a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing. She is the author of Everything Good Will Come, Swallow, News from Home, A Bit of Difference and Sefi Atta: Selected Plays. Atta has received several literary awards, including the 2006 Wọlé Ṣóyínká Prize for Literature in Africa and the 2009 Noma Award for Publishing in Africa.

SEFI ATTA was born in Lagos, Nigeria, in 1964 and currently divides her time between the United States, England and Nigeria. She qualified as a Chartered Accountant in England, a Certified Public Accountant in the United States, and holds a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing. She is the author of Everything Good Will Come, Swallow, News from Home, A Bit of Difference and Sefi Atta: Selected Plays. Atta has received several literary awards, including the 2006 Wọlé Ṣóyínká Prize for Literature in Africa and the 2009 Noma Award for Publishing in Africa.

Author’s Facebook page

Visit the author’s website

Follow her on Twitter @Sefi_Atta

Save the date! On on Sunday, May 7, 2017, Nigerian writer Sefi Atta will be signing her new book of Selected Plays at the Art Gallery, Freedom Park, Lagos.

Save the date! On on Sunday, May 7, 2017, Nigerian writer Sefi Atta will be signing her new book of Selected Plays at the Art Gallery, Freedom Park, Lagos.