This was written in early 2020 and it was never published — in part because of the global pandemic that started shortly after, but mostly because it was supposed to be a private record of my trip to learn a bit more about the state of libraries and documentation in my country while I worked as a research fellow at the British Library in London. I’d always been fascinated by libraries and their role in the preservation and reinforcement of culture and history (Here’s one of my last visits to the best small library in America in 2010) so working at the BL brought many of my questions and curiosities to the fore. I went back to Nigeria to connect some dots that hadn’t yet made sense. I found the report in my drafts yesterday and I realised that it does stand alone as an important record. Still not satisfactory of all the queries I had then, it remains important as a guidepost to anyone else interested in the issues. Also, since then there have been some new private efforts in documentation in Nigeria, one of which is Archivi.ng, which gives me hope for the future.

***

I spent much of my time in Lagos between February 12 to March 1, 2020, learning about the library and archival culture in Nigeria. Until my fellowship began last September, I did not even know that there was a National Library in Nigeria, where it was located, or whether it was accessible for use. This was partly because I never looked, and also because — if it existed — enough work hadn’t been done to make citizens aware.

When I was in high school, the closest ‘library’ around me was a private one, run by the Association of Reproductive and Family Health (ARFH) which owned the building in which it was located. They had made contact with my school as a way of introducing teenagers to information about reproductive health. So after school, we went to the building, where we could borrow books, spend some time in the reading rooms, join reproductive health clubs, and participate in a number of activities that complemented our learning in school. If there were public libraries in Ìbàdàn at the time — and my knowledge now shows that there were — I had no idea. At least in Ìbàdàn, there is a state library, a publicly funded library open to everyone. But it was centrally located and far from where my school was.

But on return to Lagos this February, I was more interested in learning about the National Library, which I believed would be the equivalent of the British Library in the UK — an organisation which collected all the books published in the country, which ostensibly had a record of all the books that have ever been published, had accessible reading rooms, and served about the same purpose as the BL does in the UK.

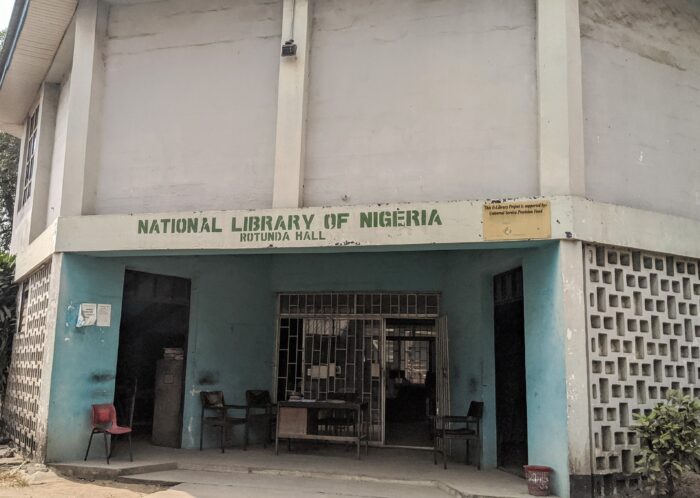

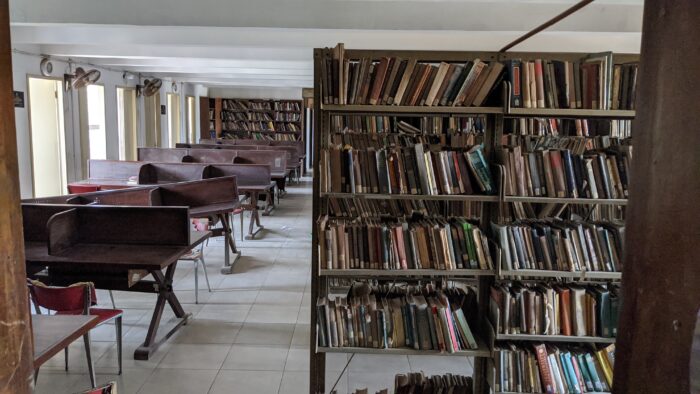

Through social media, I found that there was an office located in Yaba in Lagos. So I drove there on February 21. It was located off Herbert Macaulay Road, in an alcove that made it easy to miss from the main road. Even the sign had been obstructed by a half-broken fence and an electric pole. Still, there it was. The compound was big enough to allow for parking. The building itself was spacious and the visit looked promising. Outside, by the fence, were a couple of students reading on small tables.

At the National Library branch in Lagos

On my way in, I noticed shelves and cupboards placed outside, and in positions that suggested that some renovation was going on. This would be confirmed later. The Library was out of service on this day. Some renovation was going on that would not be complete for a few weeks. So only a few skeletal services were available. Even the director was not around. But I found two officers who would speak to me and answer some of my questions.

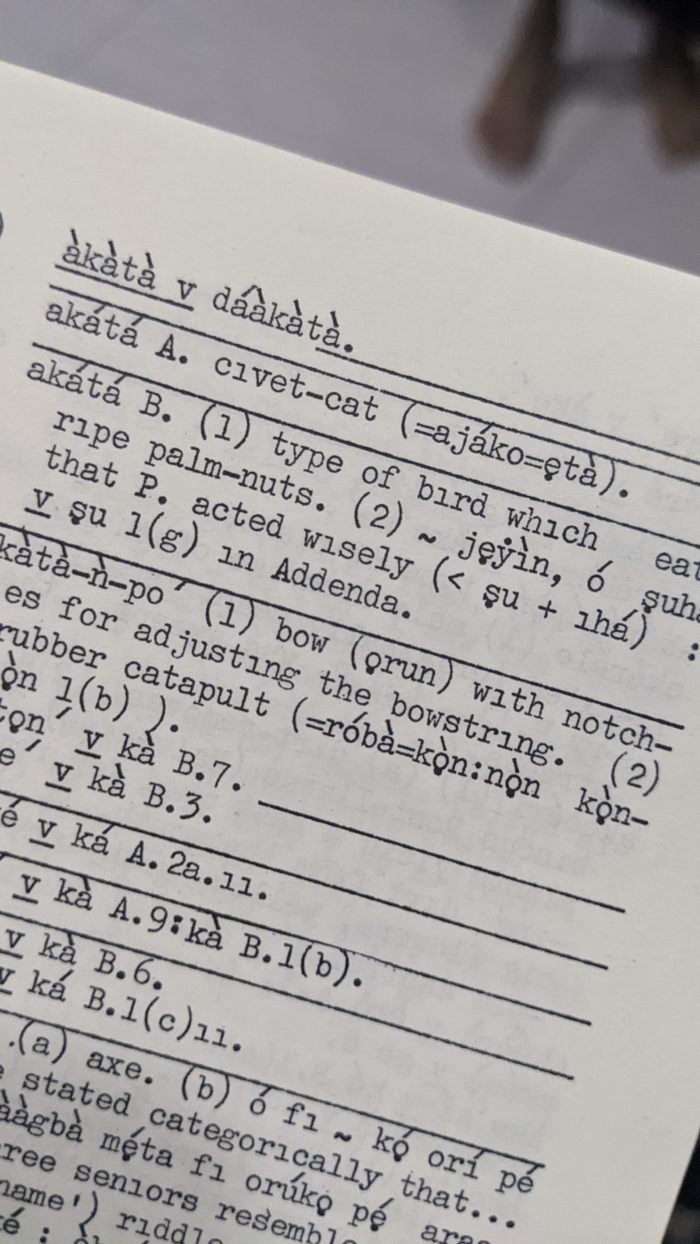

One of the things I was curious about was Legal Deposit, the law that mandates that every book published in the country be sent to the National Library for keeping and archiving. I knew, by having read up on it (some links are online here, here, and here), that the law existed in Nigeria, but I didn’t know how it worked on the ground. I was also curious about how it was being implemented.

In Nigeria, the law mandates at least three copies of books to be sent to the National Library in the state where the book was published. There are 27 branches of the National Library though more are being considered for the other states. The plan, according to the person who attended to me, was to have a branch in each of the 36 states in Nigeria. These three copies are then sent from the local branch to Abuja, the headquarters, where a bibliographic record is made, after which one of the copies of the book is retained in Abuja, one is sent to the Kenneth Dike Library at the University of Ìbàdàn, while the final one is sent randomly to any one of the 27 branches around the country.

The Nigerian Legal Deposit law, it seems, stems from the fact that the Nigerian National Library is also the source of all ISBN numbers issued for books about to be published. This is not the same in the UK. So maybe the thinking is that publishers hoping to continue to get ISBN numbers will hold up their own part of the bargain by continuing to send in published books as required by law. I was surprised to find that, in spite of this, there are still some publishers who either forget or choose not to send in their required legal deposit. The woman who spoke to me said that there are some enforcement mechanisms to take care of this. Visits are often made to these publishers to remind them of their responsibilities.

So, because copies sent to the branches are selected randomly, no branch in the country has all the titles published that year. And none can boast of having copies even of the books published in the state. I found it interesting. I was also fascinated by the new discovery that the library in my alma mater, the University of Ìbàdàn — called Kenneth Dike Library — had copies of all the books published in the country since the establishment of the National Library in 1964 or even earlier. The suggestion was that even colonial legal deposit materials would be there. And so I arranged to visit it. But I was also interested in visiting the Ìbàdàn branch of the National Library, if only to compare the services, the environment, and the structure. I was also interested in at least making a connection, for the British Library, with the curators there.

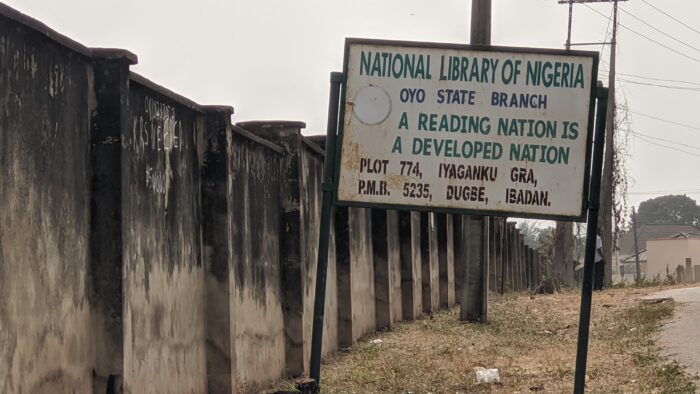

At the National Library Branch in Ìbàdàn

The Ìbàdàn branch of the Library is at Iyaganku, across from the Customary Court of Appeals. It had a wider compound. The building used to be a residential house for one of the country’s earliest leaders and politicians. It was said that Anthony Enahoro once lived there. Even the compound of the Customary Court once hosted the second Premier of the Western Region, Chief Ládòkè Akíntọ́lá, who was murdered there during the first coup d’etat in January of 1966.

On the fence on my way in was the poster for an event that happened many months earlier inviting the general public for a sensitization workshop “on Legal Deposit Compliance and ISBN & ISSN” Inside, after parking, I got in, and met a number of workers there who showed me the reading rooms, the storage rooms, and answered a number of questions I had about the challenges they have with running the place, attitudes of users, the state of libraries in Nigeria, and other things. They also asked me about the British Library, what I did there, and how to better create a collaboration between the two institutions.

The director wasn’t around on this day either, so I arranged to return, especially after seeing Kenneth Dike Library in Ìbàdàn.

At Kenneth Dike Library, University of Ìbàdàn.

KDL, as we often called it, is as old as the university itself. I had spent some time there as an undergraduate between 2000 and 2005. I just hadn’t known that it was also a library of archival records. Its role as a repository for all legal deposit materials was a revelation that I was interested in exploring.

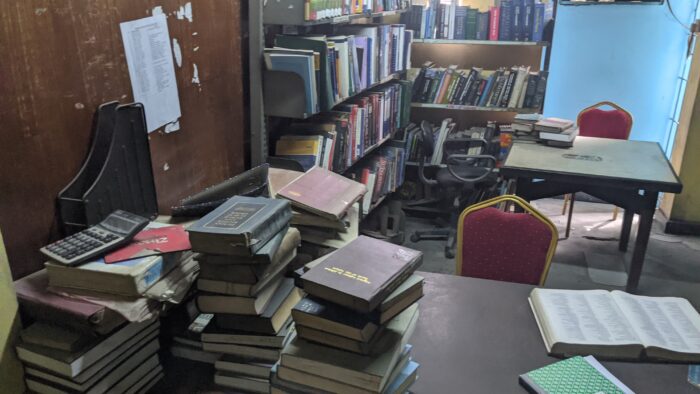

I secured a meeting with the Head Librarian for a conversation. There was a strike action of non-Academic staff on the day I went there on February 25th, so she had some free time. We talked for almost an hour, some of which were productive. Mostly, she appeared either unfamiliar with the role of the Library as a legal depository for books from the National Library, or not understanding of my questions and follow-ups about where exactly one could find those books. The focus of the Library, she said, was on academic publications. Acquisitions are done only for publications that would help the students and professors in their research. All other materials — including fiction, history, or other “irrelevant” ones — are regularly pruned from the shelves to make way for these important ones. She also did not know much about colonial legal deposits, which I had been told at the Iyaganku branch of the National Library should also be in the holdings of the Kenneth Dike Library.

After a generally unhelpful conversation, I proceeded downstairs to speak to someone she had recommended had sufficient knowledge. This was Seun Obasola, who happened to have been my predecessor at the British Library as the Chevening Research Fellow. If the last hour had been frustrating, the next three were the opposite. Obasola, who had worked at the Library for over ten years, knew its ins and outs. She knew that KDL was, indeed, a repository for legal deposit materials from Abuja (and had an idea of where I could find them). She also admitted the already obvious fact that many people who currently work in, and occupy high administrative positions in, the Library might not always be the most knowledgeable about the location of many of its holdings. She pointed to me the storage areas where many archival and historical materials belonging to the Library from way back were stored, sometimes in terrible conditions. She is currently applying for an EAP grant to catalogue and digitize some of them. The sad fact, she said, was that there was just too much, and too little manpower. Thus, over time, materials just get piled up with no one knowing where they are or what to do with them. More funding, and more manpower would be very helpful. Not helped, also, is the fact that she herself was just about to begin another two-year fellowship in Canada, which may take her even farther from a place that needed her competence so badly.

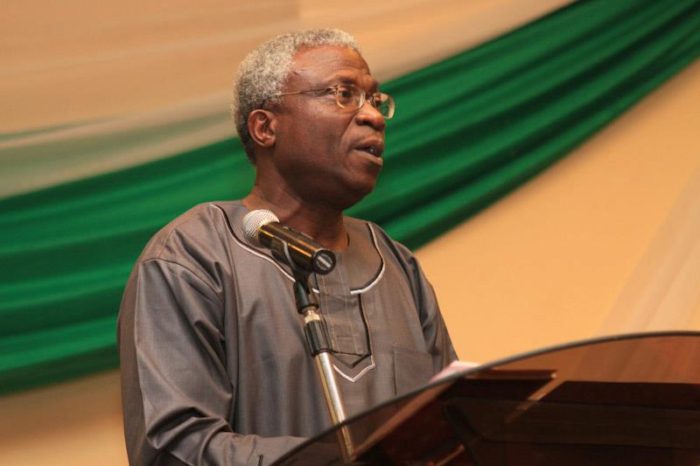

It was a delight to hear that the catalogue records of KDL — at least of the materials that have been found and properly stored — was almost all available online through the online public access catalogue. Like the BLExplore page, one could search for any item in the KDL catalogue even without being on the physical premises. This is not the same for the Nigerian National Library, where manual cardboard catalogues are still being used. I was told that the Abuja office had an electronic record, but it just wasn’t online. It seemed unhelpful to think of a national library without a nationally-accessible catalogue, but that’s where we currently are. I have harboured the hope of one day meeting with the National Librarian, Professor Lenrie Ọlátòkunbọ̀ Àìná, whom I have been told is a progressive-leaning administrator, to discuss these questions.

The Biggest Issues

It seems, from my experience during this visit, that the biggest issues in public library administration are funding allocation and management.

The 2020 budget for the organisation was 2.9 billion naira (£6.12 million). This looks small compared to the annual budget of the British Library which is currently at £142 million but for what services it can offer in Nigeria, that is a lot. It is perhaps not efficient to have 27 branches (while aspiring to have 9 more). Current overhead costs are 227.9m naira (£480,965.24) which could probably be better used for acquisitions, digitization, storage, and other expenses. The capital expenses cost 1.6 billion naira (£3.37 million). From what I saw in Ìbàdàn and Lagos, which should certainly be the two most prominent centers apart from the HQ, that money is terribly spent. The computers don’t work. Those that work aren’t being used by students. The catalogues are still manual. There is no electricity or inverters to provide power. The generators are rarely on, and people who use the reading rooms are often in quasi-dark environments. The library’s branches do not pay for their own acquisitions, and often even turn their backs on donations, for lack of space to store and preserve the materials being donated. I would be interested in knowing what capital expenses were made with £3.37 million every year!

The other, of course, is leadership. Until I speak with the National Librarian, I will have nothing particular to say here. But I hope to in the future. He apparently has a home in Ìbàdàn, and comes around often, every few months. Putting the right directors at each center — who know what is right, and who are capable of better managing the funds allocated there — might be a way out. One, of course, needs transparency about how much is being allocated to each branch. None of this information was made available to me, for the obvious reason of my non-insider status. But there were insinuations, particularly by the lower members of staff that I talked to, that mismanagement was also a part of the problem.

Everyone I met had mentioned the Olúsẹ́gun Ọbásanjọ́ Presidential Library in Abẹ́òkuta as one model of a decently managed and decently run library in Nigeria. It was founded shortly after the tenure of the man in whose name it was built, who had then ruled Nigeria for the second time as a civilian president. It turned out that Chief Ọbasanjọ́ himself had been instrumental in securing the land for the permanent site of the National Library in Abuja, and was a passionate advocate for proper archiving and documentation in Nigeria. So I was intensely curious about meeting him. Unfortunately, my time in Lagos had run out by the time the necessary arrangements were made, and I could not make the trip to Abẹ́òkuta. I intend to do this on my return from the fellowship. The Presidential Library, according to those who have visited it, boasts of a number of relevant records in Nigerian political and social history, and also the life of its patron as well, who was imprisoned in 1995 on the accusation of being an accessory to a fabricated coup. He was freed in 1998 as part of the amnesty programme of the subsequent military administrator. He became a candidate for office that same year, and was elected president in 1999.

One of the limitations, I believe, in getting sufficient funding for the Nigerian National Library is the ban on fundraising. All the funds for running the Library is given by the government. The act setting it up also prohibits any fundraising of any kind. So people can use it “free”. The result of that is that if the money disbursed from Abuja is insufficient, the library and the books suffer. At the British Library, at least one could pay to become a member, or use venues in the Library, or buy food at the public cafeteria. The BL also gets private funding, for activities such as the Endangered Archives Project or the Eccles Center. Those help support the Library as a public institution. I saw no sign of any such public-private partnership with the Nigerian equivalent. Perhaps changing the laws to make this possible, and allowing the branches to make money through small services, will help improve their use and competence.

There are a number of grants that have supported library work in Nigeria. A sign at the Yaba branch says “This e-Library Project is supported by the Universal Service Provision Fund.” In Ìbàdàn, I learnt about TETFUND, which is a fund dedicated to helping tertiary institutions in Nigeria. Kenneth Dike Library got some of it. EAP at the BL has also been named as a potential funder for some documentation projects. These and many more can be helpful if properly managed.

Other Libraries, Comparisms, Conclusions

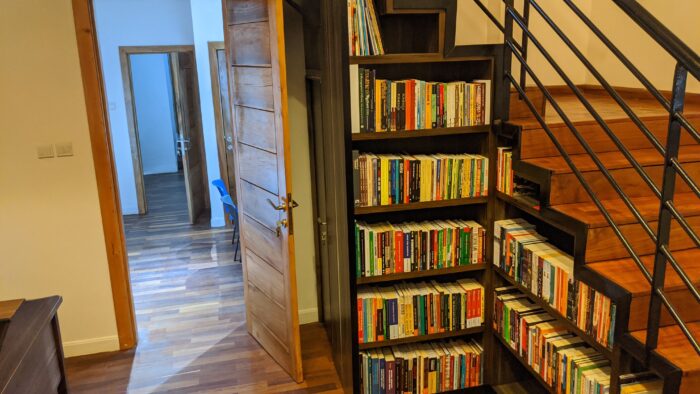

In Nigeria today, especially in more metropolitan places like Lagos, private libraries and reading spaces are springing up. In the same Yaba, about a kilometre or so from the National Library, there is a new private library renovated by a private bank and used to host readers and other enthusiasts. Some public events have been held there as well, including the famous one where a Guinness Record was made in 2018. There are also state-controlled public libraries which, very likely, suffer from the same problem as the federal one. One of my favourite places to go in Lagos, of course, is the Ouida House. It is not a library per se, but a bookshop with a public-facing side. It also has a reading room that is accessible.

But in all, the library I found closest in ambition, scope, capability, and history, to the British Library is the Kenneth Dike Library in Ìbàdàn. With better funding and management, it might do even better. I suspect that the Hezekiah Oluwasanmi Library at the University of Ifẹ̀ comes real close, but I never got a chance to explore it either.

____

Thanks to Budgit for some of the budget figures I used here.