by Yẹ́misí Aríbisálà

___

My name is Yẹ́misí Aríbisálà. Because of context I must state that I am not a feminist nor will I ever be one. As made clear from the paragraphs below, the “or else” will come to my door and meet it open.

My name is Yẹ́misí Aríbisálà. Because of context I must state that I am not a feminist nor will I ever be one. As made clear from the paragraphs below, the “or else” will come to my door and meet it open.

Over the last few months and especially after an interview in recent days, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has become the woman that we all love to hate. What irony. I only have one indictment for her regarding the attacks on social media for words spoken to the press in that interview: It is that she wittingly contributed to the creation of the “We”, the same mob that turned against her. It is what happens when people are not allowed to go away and really think and decide what they believe as individuals, and they are coaxed and persuaded and ushered into making decisions in groups. What happens when we all become a “body of feminists” without a a coalition of working, dissenting brains is that we are and become a mob.

The most recent social media uproar against Adichie is over her differentiation between feminisms – hers and Beyoncé Knowles-Carter’s. It is allegedly also about Adichie’s arrogance and the way she expresses herself that seems to condescend to the person being addressed. It is about causing a rift between feminists and seeming thereby to designate some as intellectuals and others as liberal and possibly nonintellectual. That feminists should not be distinguished thusly is the crux of the protest. Lastly it is about a supposed change of position indicated by Adichie’s permission to Beyoncé three years ago to use her words in the song Flawless suddenly retrospectively retracted in the interview. Or if not retracted, sidestepped in a clarification that said that giving permission for the use of her words in no way indicated that she and Beyoncé’s feminisms were moving along the same track.

So people are angered by the backtracking and the condescension and the lack of acknowledgement by Adichie that she got plenty of mileage in allowing Beyonce to insert her words in her song. But really the whole thing is about being fed up with Adichie’s condescension.

Here are my thoughts:

Adichie’s responsibility to her audience is completely different from Beyoncé Knowles-Carter. Both may be in the public eye but Adichie is an intellectual and a woman of words. Someone whose philosophy cannot and should not be ignored. It is not a philosophy of entertainment that belongs to Beyoncé. The philosophy of entertainment allows all kinds of things that real life will not accommodate. For example, a woman in entertaining people may take her clothes off and bend over to show her crotch in front of a room full of people and they will clap and encore her. In real life, she cannot do this, she may be dragged off to an asylum.

If certain people do not like the fact that the artist has exposed herself, they don’t have to go to her show the next time, and if she really offends, she can pass it off as intrinsic in the licence of artistic expression. Not so Adichie. Even though she doesn’t have a very effective PR body advising her on how to manage the balance between the transience of celebrity and the more crucial creation of art and a strong body of ideas that will surely outlive her, she is still operating in real time, in real life where people do not react liberally or placidly to the showing of crotches and cleavages and erotic dancing. Even when people try to pretend that they have blurred the differences between entertainment and reality, we should not believe them. They are being false. Real life is real life and entertainment is entertainment. And we all understand that no matter what happens in the rooms of Big Brother Africa, the contestants have to go home.

I do not like Beyoncé’s art nor her expression of it, but that is irrelevant because I don’t have to go and watch her or buy her records. More importantly, because she is an entertainer even if one who likes to include political material in her art, I don’t have to take anything she says to the bank. I don’t have to accept her philosophy of life and relationships. I don’t have to ascribe to my daughter sitting in a car and performing oral sex on a man and agree that this is liberal and open-minded. I don’t have to take her seriously at all. I don’t have to take a bat to a car. The agreement is that she is an entertainer and even if I am carried away by her beauty and power, and feel all hot and wonderful after her show, I don’t have to believe any of it. This is the contract of entertainment that exists but which people are attempting to falsely blur. Beyonce’s art is often about channelling pain and joys of relationships with men with very questionable language. The nudity, sexual language, and violence are in my opinion not powerful at all – not in any way about real power – and should be considered with great caution even in the realms of entertainment. But I am unwilling to tell people what to consider as entertainment. I love Billie Holiday’s music but on no account can I consider her doormat hood to husbands and lovers as expressed in her art as a sensible philosophy to life.

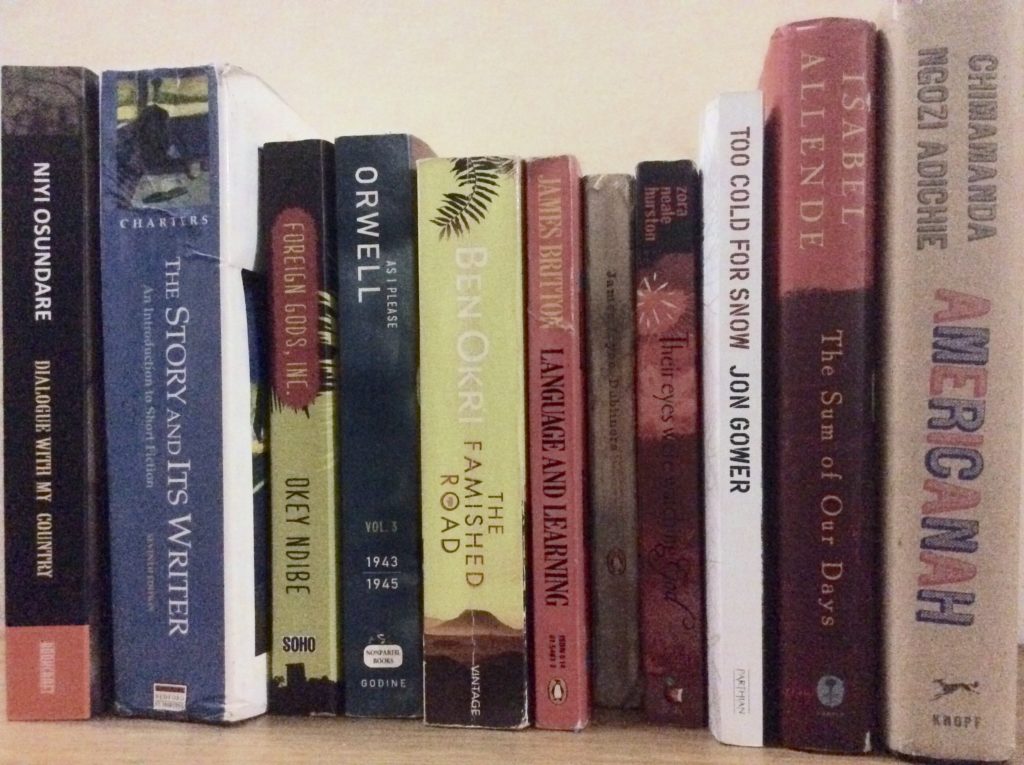

The contrast is that we cannot ignore Adichie. Not only because she carries enormous intellectual potential whether we like her or not, and possesses a great influence over generations of Nigerian women, but also because her views are daily being written down and concretised. She is a philosopher of real life in real time. More importantly, Adichie belongs to Nigeria and she is a beacon of that which is possible for the Nigerian woman. We cannot underestimate her worth nor her work. The attempts to disregard her are also a falsehood. Having said that, I must add that I dislike Adichie’s Americanah’s treatment of relationships between men and women. Her portrayals of traditional, non-“liberated” women in that work are uncharitable and tapered. Without a good balance of her art, her work, and her personal brand, she willingly inserts a fragility in her writing. Again I cannot take liberties in telling people how to live their lives. She can do what she wants. Adichie in the end is a powerful Nigerian intellectual with serious responsibilities.

In my opinion if Adichie informally retracted the permission she gave to Beyoncé to use her words in her song Flawless, then it was the right thing to do. Retrospectively, it is the right thing to do. If she never really gave it, then even better for Adichie’s ideas are in fact too good for Beyoncé’s entertainment. Too bad if Adichie did not know that, or if she saw it as an opportunity three years ago to get her words attention. If a person makes a decision one year then three years later changes that decision. That is what is called growth. And rather the person should be commended for growing and for changing their minds than castigated for speaking.

I will never pretend that I don’t change my mind.

The Yorùbá hold as sacred the head. That head has a mouth in it and each person has a head and a mouth. We can take this as a pointer towards individual thought and speech. We all have our irritating quirks, our mannerisms that rub people the wrong way, our crazy headless ideologies. We are all work in progress.

I am appalled that I can count on the fingers of one hand the people who stood up for Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in a week of strong personal attacks against her from women like her, from women to feminists on social media. Not surprising, as a few weeks before that on Ikhide Ikheloa’s facebook page it was the annihilation of another woman, Abiodun Kuforiji Nkwocha, using language that made one’s mouth fall open in shock and disgust.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is not a friend, a relative, nor even an acquaintance that I bump into once a year. I did sit next to her for two weeks in 2012 during the Farafina’s Writers Workshop. I disagree with many of her ideas, as I am sure that she disagrees with mine. Yet I have a responsibility to look at her and say – this is a woman like myself, with her own traumas and challenges and insecurities. More flesh and blood than a feminist philosophy or tract. More present than BBOG or some vague profile of a woman who is a victim of domestic violence, or some powerless hungry hawker of a girl. She is a woman, a mother and a wife. One day her daughter might google in her name and find the hate and vitriol and ugliness spouted against her. It is self-preservation on my part. I don’t want my daughter to be the google-r and see that I am a grasshopper in a swarm of locust attacking one person by consensus – telling her she cannot speak her mind. My role as a woman is not to gag other women and take away their voice – whatever it sounds like. Debate(s) should, happen but not on vicious personal terms.

Why be the fighter for the rights of some faceless woman who I don’t know when I am going to be part of a mob rolling out the old tires and lighting a fire for burning another woman That I Do Know. If you do not like the woman, nor agree with her, is it possible to agree to disagree with decorum then let her be? I can determine that I find her tone arrogant but I don’t have to retaliate arrogance with arrogance. I can stay out of her way completely if it helps. I don’t even have to accept her philosophy for real life either. I don’t. Whatever my decision, it must be clear that like all tides things have a way of turning around.

Why be the fighter for the rights of some faceless woman who I don’t know when I am going to be part of a mob rolling out the old tires and lighting a fire for burning another woman That I Do Know. If you do not like the woman, nor agree with her, is it possible to agree to disagree with decorum then let her be? I can determine that I find her tone arrogant but I don’t have to retaliate arrogance with arrogance. I can stay out of her way completely if it helps. I don’t even have to accept her philosophy for real life either. I don’t. Whatever my decision, it must be clear that like all tides things have a way of turning around.

I hope that if a mob does stand opposite me one day, someone will say “I know her, that lady that cooks moin moin on the internet. Let her be.”

____________

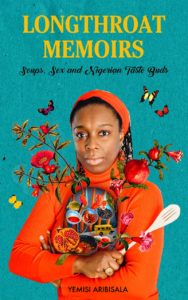

Yẹ́misí Aríbisálà is the author of a new memoir titled Longthroat Memoirs: Soups, Sex and Nigerian tastebuds. (Cassava Republic, 2016)