Here are some of my favourite shots from Ostana, Cuneo, a trip I’ve written about extensively already. These shots feature informal and formal activities around the Premio Ostana Prize which lasted almost all week. In it are my wife, sponsor, Valentina Musmeci, Lọlá Shónẹ́yìn, colleagues, visitors and fellow prizewinners.

Here are some of my favourite shots from Ostana, Cuneo, a trip I’ve written about extensively already. These shots feature informal and formal activities around the Premio Ostana Prize which lasted almost all week. In it are my wife, sponsor, Valentina Musmeci, Lọlá Shónẹ́yìn, colleagues, visitors and fellow prizewinners.

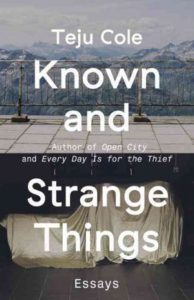

I’ve been reading Tẹjú Cole’s Known and Strange Things among other commitments. The book is a collection of published and unpublished essays by the acclaimed author of Open City and Everyday is for the Thief, two books noted for their essay-like forms that brilliantly blur the lines between travel writing and fiction. As a travel blogger, I can relate. He also follows in the tradition of many other writers famous for documenting their travel adventures in their literary output. The book is a compact curation of his own writing journey from many publications in which a number of them had first appeared.

I’ve been reading Tẹjú Cole’s Known and Strange Things among other commitments. The book is a collection of published and unpublished essays by the acclaimed author of Open City and Everyday is for the Thief, two books noted for their essay-like forms that brilliantly blur the lines between travel writing and fiction. As a travel blogger, I can relate. He also follows in the tradition of many other writers famous for documenting their travel adventures in their literary output. The book is a compact curation of his own writing journey from many publications in which a number of them had first appeared.

In one of the essays in the book, Cole famously follows James Baldwin to a city in Switzerland in order to re-live that writer’s experience in the sixties while he was working on Go Tell it on the Mountain and to reflect on what may have changed over the course of time. In another, he documents his meeting with V.S. Naipaul in New York, being awed by him but not too much as not to be aware of the man’s occasional condescension that comes out at unexpected moments. “He speaks so well,” Naipaul says of the African author and we glimpse from the skill of retelling that it wasn’t that much of a compliment. In An African Caesar, the author does a nuanced review of a theatre presentation by the Royal Shakespeare Company at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, but doing it against the background of other ironies and coincidences riding on the lives of Shakespeare, Caesar, Abraham Lincoln, and the all-black cast.

In the preface, Cole pays homage to one of his (and my) favourite tongue-twisters from Yorùbá (“Ọ̀pọ̀lọpọ̀ ọ̀pọ̀lọ́ ni kò mọ̀ pé ọ̀pọ̀lọpọ̀ ènìyàn l’ọ́pọlọ l’ọ́pọ̀lọpọ̀”) to illustrate his rootedness in his home culture properly balanced with his accommodation of other cultures and values. In another part of the chapter he expounds this more clearly:

“There’s no world in which I would surrender the intimidating beauty of Yoruba-language poetry for, say, Shakespeare’s sonnets, or one in which I’d prefer chamber orchestras playing baroque music to the koras of Mali. I’m happy to own all of it. This carefree confidence is, in part, the gift of time… I feel little alienation in museums, full though they are of other people’s ancestors… I am not an interloper when I look at a Rembrandt portrait. I care for them more than some white people do, just as some white people care more for aspects of African art than I do…”

The tongue-twister was, impressively, left un-italicized as have typically been the case in most books published abroad. It was, however, not properly tone-marked as Yorùbá words usually ought, and as I did above. Neither were any Yorùbá names referenced in the work. My initial assumption is that this is the publisher’s error, typically paying less attention to proper diacritical marking on non-English words. But elsewhere in the book (Furtwängler, Tété-Michel Kpomassie, Florian Höllerer, Tomas Tranströmer, Galápagos, etc) names belonging to other people in accented/tonal languages were properly accented with no eyebrows raised. Here, my initial elation at the central featuring of Yorùbá in this work was greatly punctured, and now awaiting sacrificial appeasement and repair. In 2016, we should no longer be apologetic about insisting on proper writing of African languages in literature. The writer, certainly, at this height of his literary career, stands in a great position to influence this change.

My favourite essay in the work yet is an essay titled Unnamed Lake which is a stream-of-consciousness-type narrative on the complexity of perception, art, and the role of memory. It is one I’ll also read again for its layered presentation that offers new gem each time. I like it also for its use of mixed metaphors from French/Algeria (Derrida) to Germany (Wilhelm Furtwängler), from Australia (the Adnyamathanha people) to Nigeria (Major Patrirck Chukwuman Kaduna Nzeogwu), from Bangladesh to Hiroshima (President Truman). The other essays more grounded in recognizable reality of the author’s work history: reviews (Wangechi Mutu), polemics (The White Saviour Industrial Complex), satire (In Place of Thought), and interview (A Conversation with Aleksandar Hemon), etc, are equally enchanting, and serve a purpose of providing a wide appraisal of Teju Cole’s worldview.

My favourite essay in the work yet is an essay titled Unnamed Lake which is a stream-of-consciousness-type narrative on the complexity of perception, art, and the role of memory. It is one I’ll also read again for its layered presentation that offers new gem each time. I like it also for its use of mixed metaphors from French/Algeria (Derrida) to Germany (Wilhelm Furtwängler), from Australia (the Adnyamathanha people) to Nigeria (Major Patrirck Chukwuman Kaduna Nzeogwu), from Bangladesh to Hiroshima (President Truman). The other essays more grounded in recognizable reality of the author’s work history: reviews (Wangechi Mutu), polemics (The White Saviour Industrial Complex), satire (In Place of Thought), and interview (A Conversation with Aleksandar Hemon), etc, are equally enchanting, and serve a purpose of providing a wide appraisal of Teju Cole’s worldview.

What are essays good for? Setting an agenda, making a point, codifying for a coming generation thoughts, ideas, arguments, and questions plaguing a specific time? Mr. Cole’s collection touch on many of these as a timely intervention not just for identifying his own outlook on the world – though this is relevant – but also for leaving a mark identifying this place and this time as his point of visiting. Like a traveler in the desert on the way to somewhere else choosing for a while to make artistry from the sand under his feet not only to delight himself (and how discomfiting would that be in a scorching desert?) but also to amaze overhead flyers and future visitors to the place with his own creative interpretation of what he had experienced.

In that way, essays are not that different from memoirs, which tap into memory and creative writing to attempt an understanding of the past through the narrative lens, except that they tell more than they show, opening to us directly the thoughts and opinions of the writer. What we take away is more than knowledge of the subjects and places we walked through with the writer, but also something about the writer himself. Known and Strange Things tell us that the brilliant Teju Cole is curious in his approach to life, attentive things that connect us with those who have gone before, of different colors, cultures and tongues, and diligent in his retelling of (or at least his arguments about) what makes them memorable or relevant, allowing us to walk in his shoes page by page. That makes the book an engaging, and important, read.

____

Photo credit: TheGuardian.com

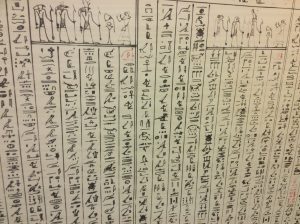

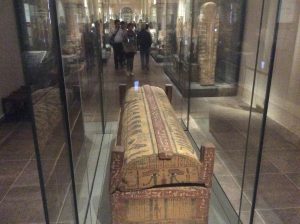

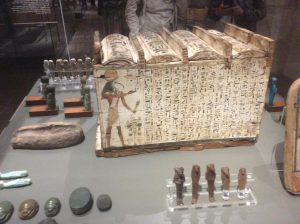

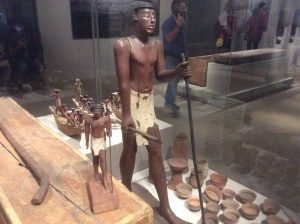

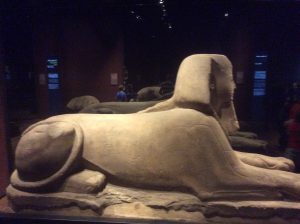

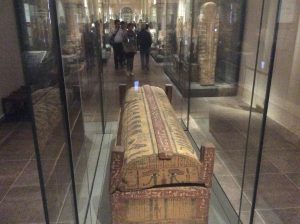

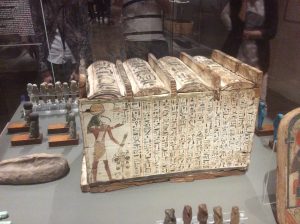

I’d leave this post to speak for itself through the pictures taken at the Turin Egyptian Museum. But I’m leaving the pictures here for another reason: to save my hard drive from having to store up all of these for all eternity. Photos, like the many of the dead relics in the museum, must – if they will live forever – find a well-visited and well-curated place worthy of their presence.

I must, also, strongly suggest that anyone who cares for ancient history, art, and Egypt should check out the museum. It is worth spending the whole day enjoying, and learning from.

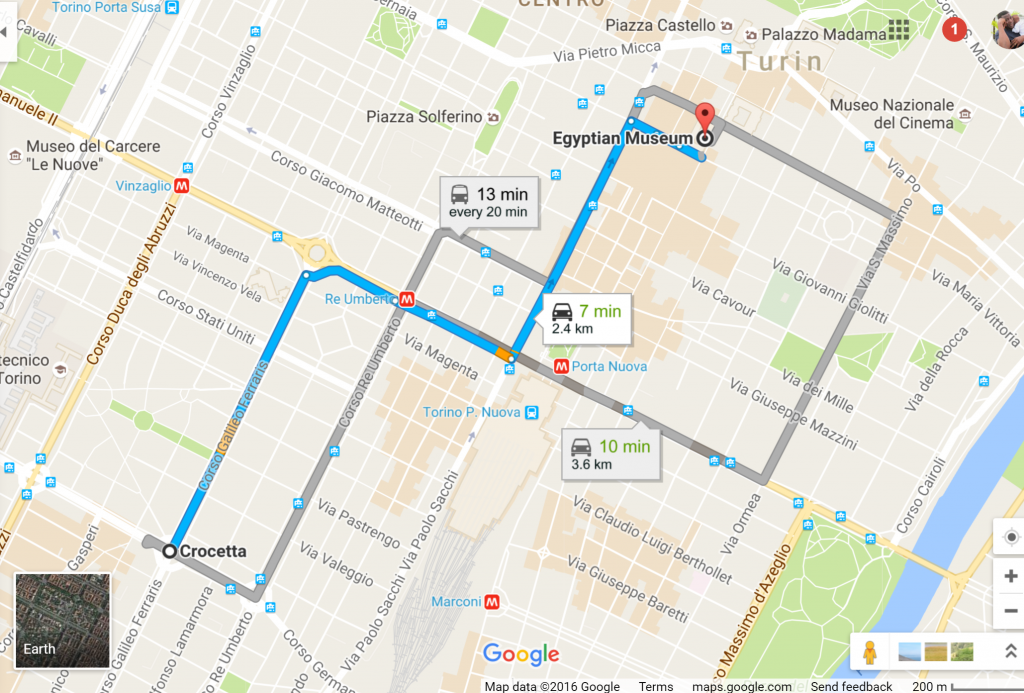

Getting to the Egyptian Museum from central Turin was supposed to be straightforward, but the mapping of someone else’s city always looks easy on paper. What we planned, the five of us cramped excitedly into a small car in pursuit of the mysteries of the Torino archaeological museum, was to get ourselves into the city center, disembark, and then take one of the numerous city trams towards the museum itself. Simple enough. In reality, when we landed at Crocetta – which isn’t the city centre as much, but just slightly south of it, a few of us needed cash from the ATM machine, some needed a smoke, all of us were hungry, and time was ticking. Two members of the group had a plane to catch in a few hours.

The first impression of Crocetta isn’t notable, perhaps because the town wears a garb of normalcy that seemed out of place for some reason. But reading later that it is one of the most prestigious neighbourhoods in Turin puts that atmosphere in context. One thing I remember is how tall the buildings were and how much they seemed to extend into each other, with long corridors that stretched as far as the eyes could see. I realised, eventually, that this isn’t a localised phenomenon but an Italian thing. Not just the buildings, by the way, but the roads too. Inspired by the military strategies of the Roman empire, most streets and buildings were built in such straight lines as to allow an observer to see as far ahead as possible from one location.

The ride to the museum was as bumpy as most tram rides are, and sufficiently contrastive with both the earlier ride in a private vehicle and a typical city commute in another familiar city many thousands of miles away. A recurring thought in the traveller’s head in moments like this is the extent of work that would be needed to modernise a city like Lagos to this level of infrastructural development. A tram, after all, is just a fancy name for a longer-than-usual bus that runs on a designated track and with electricity. A weightier matter on the mind was something of far greater significance that had happened just a few days prior: I’d lost my younger sister in Lagos to preventable maternal mortality and the Nigerian healthcare system. Every opportunity for interaction with things signifying of the continuation of life seemed satisfying enough even in their imperfection.

It makes sense now, everything already said about loss and the perspective it brings. Being far away from the scene of grief, where nothing was ever going to remain as they were, was no consolation, and certainly no relief. So, going through the halls of the Egyptian Museum, travelling into the past where death and renewal were matters of natural law and importance only provided temporary but welcome succor. Sarcophagus, scrolls, mummified remains from hundreds of years ago still remaining intact in their exhibition cases spoke to far more than the ability of humans to preserve that which is no longer practically immediately useful, but also to the value of that pursuit itself, capable of revealing (or ennobling) something more about ourselves than about those already dead.

With over 30,000 artifacts, I often wondered how long it took to excavate much of the work currently exhibited in the museum. The first item received, according to Wikipedia, arrived almost 400 years ago. A more awe-inspiring question is about how much more of these types of work with spiritual-artistic significance from that ancient civilization is still left buried under the many ruins in today’s Egypt, and how much more they may still inspire us. And also, a little unnerving, what chance of survival would many of them have had they been left in their homeland rather than having been transported over the distance into this beautiful place in Turin. Perhaps many of these gods are glad to have been saved from the fanatic distress currently sweeping through the Middle East.

The ride back to Crocetta was, perhaps, slightly more animated than introspective, as the aftermath of spending two hours staring through enchanting history. We had plenty to talk about, gifts purchased at the gift shop to compare, and promises to make that we would return here at a later date for a more thorough exploration of an exhibition that couldn’t possibly be properly enjoyed in less than two hours. Then we alighted from the tram and couldn’t find our car. We had got down at the wrong stop. Ten to fifteen minutes later, we found the car parked safely where we’d left it, at a location similar to all the other spots on all the other similarly-looking streets we’d had to walk through, sometimes terrified of staring groups of strangers, and sometimes nervous about LS and her daughter missing their flight.

Having a street with so similarly-looking blocks of buildings, with very few (to a stranger) landmarks to help navigate, it turns out, had its negatives.

My impression of Turin, from never having ever visited it, was limited to an article in the Reader’s Digest from 1984 called The Shroud of Mystery by J.H Heller. Not just an article, however, but a specific image of a piece of linen cloth with an imprint of a face said to belong to none other than Jesus Christ of Nazareth. Reading the piece as a young teenager in the early 90s Ìbàdàn was as exciting as it was disturbing. Having the pleasures of discovering reading as a worthwhile endeavour come with the unpleasant imprinting of an intriguing yet disturbing image didn’t seem at the time like a fair deal compared to all the fun my other friends were having. It compensated later, if only slightly, by the usual pleasures that reading brings (learning the meaning of “shroud”, for instance) and the stimulating dimension of that particular story: after Jesus died and was wrapped up, his body fluids/sweat/embalming liquids ensured that the outline of his face and body left indelible marks on the covering shroud. The result was this Shroud of Turin, hundreds of years old, showing the outline of a dead man with puncture marks on his wrists, blood marks on other parts of his body, etc, which the article suggested proved the biblical story to be true and intriguing scholars and theologians forever.

Recent carbon dating on the cloth has now rendered that conclusion false. The shroud shows a dead man alright, but it certainly wasn’t the Jesus, unless Jesus was born in the 1000s – 1300s.These scientific discoveries haven’t slowed down the perception of the cloth as being divinely ordered, however, as people still spend hundreds of thousands of dollars every year to see it either as a tourist curiosity or as a religious symbol. In any case, the deed was done: this famous death-mask of a man from many years ago continued to add an unwanted dimension to my teenage nightmares.

Recent carbon dating on the cloth has now rendered that conclusion false. The shroud shows a dead man alright, but it certainly wasn’t the Jesus, unless Jesus was born in the 1000s – 1300s.These scientific discoveries haven’t slowed down the perception of the cloth as being divinely ordered, however, as people still spend hundreds of thousands of dollars every year to see it either as a tourist curiosity or as a religious symbol. In any case, the deed was done: this famous death-mask of a man from many years ago continued to add an unwanted dimension to my teenage nightmares.

Whenever I heard of Turin from then on, all that came to my mind was the image of that shroud – a holdover of idolatory in European Christianity, perhaps, as an item significance to validate one’s faith, and to hold on to for as long as possible, generating tomes of research articles, arguments, and tourism dollars in the process. In any case, I’ve always wanted to see it for myself. So when I found myself bound for Italy earlier in the year, one of the places I wanted to visit was Turin. I was in luck, as these things have often turned out for me: my plane into Italy was to land in Turin, from where I would be moved by car to Ostana, just two hours away. Even if that individual trip didn’t provide enough opportunity to explore the city, its relative closeness to my destination meant something of even purely nominal significance.

Whenever I heard of Turin from then on, all that came to my mind was the image of that shroud – a holdover of idolatory in European Christianity, perhaps, as an item significance to validate one’s faith, and to hold on to for as long as possible, generating tomes of research articles, arguments, and tourism dollars in the process. In any case, I’ve always wanted to see it for myself. So when I found myself bound for Italy earlier in the year, one of the places I wanted to visit was Turin. I was in luck, as these things have often turned out for me: my plane into Italy was to land in Turin, from where I would be moved by car to Ostana, just two hours away. Even if that individual trip didn’t provide enough opportunity to explore the city, its relative closeness to my destination meant something of even purely nominal significance.

There was also something else that I’ve always connected to Turin, but that came much recently: a 2008 movie by Clint Eastwood, set in America, and featuring a cranky old Midwesterner and his Hmong neighbours. It was called Gran Torino, named after a Ford car of the same name, which had got its name from the Italian pronunciation of Turin. Both the movie, with its story of redemption, personal sacrifice and cooperation and its soundtrack, possessed a kind of sublime beauty that was also notably memorable. According to Wikipedia, ‘the car was named after the city of Turin considered “the Italian Detroit”.’

There was also something else that I’ve always connected to Turin, but that came much recently: a 2008 movie by Clint Eastwood, set in America, and featuring a cranky old Midwesterner and his Hmong neighbours. It was called Gran Torino, named after a Ford car of the same name, which had got its name from the Italian pronunciation of Turin. Both the movie, with its story of redemption, personal sacrifice and cooperation and its soundtrack, possessed a kind of sublime beauty that was also notably memorable. According to Wikipedia, ‘the car was named after the city of Turin considered “the Italian Detroit”.’

So, it already began to seem – right from the beginning of my trip to Italy, that a number of my travel obsessions would collide with appropriate reality on the ground.

That didn’t happen, however.

The Shroud, it turns out, now comes out only once in a couple of years. Perhaps due to wear, or due to a need to create scarcity so that each outing, like of a notable masquerade, is special and memorable, those in charge of the piece of cloth only show it off once in a couple of years. And whenever that happens, according to residents, it is like a carnival: the city is full of tourists, pilgrims, and all curious visitors of all sorts, all trying to get a glimpse of the memorable fabric, and ready to pay whatever the gate fee is required at the time. “You should consider yourself lucky,” a friend said “that you aren’t here during that time. The city would be too busy for you to enjoy. And the lines to see the shroud are always very long and you have to book in advance.” It was probably all for the better.

What I was rewarded with in the end was something more: a whole day spent exploring another part of Torino which I hadn’t heard of until my trip. The city, it turns out, boasts of the second biggest Egyptian museum in the world: the Museo Egizio, which hosts more than 30,000 artifacts and receiving over half a million visitors last year alone. More on this later.

What I was rewarded with in the end was something more: a whole day spent exploring another part of Torino which I hadn’t heard of until my trip. The city, it turns out, boasts of the second biggest Egyptian museum in the world: the Museo Egizio, which hosts more than 30,000 artifacts and receiving over half a million visitors last year alone. More on this later.

That, and a memorable commute all the way from Ostana through the city of Turin in delightful company, getting lost, interacting at close quarters with a small but stimulating company, rushing through an expansive exhibition at the museum in less than two short hours, another commute to the airport to drop off (and pick up) a guest, a stopover at Barge (a midway point) for delightful pizza, and then a quiet ride home.

Without the shroud, it was still a most charming introduction to a city of so many mysteries. Perhaps more so because of its welcome absence.