By now you must have heard about the Invisible Borders TransAfrican project and a proposed trip around Nigeria starting from May 12. I catch up with the two leading members of the trip for a quick chat. Emeka Okereke (EO) is a filmmaker and photographer while Emmanuel Iduma (EI) is a novelist and art critic. They discuss what we should expect from the trip, their motivation, how we can help, among others. Enjoy.

———-

Let me start this way: How did your paths and intentions cross, the two of you? One of you is a photographer and the other is a writer. How did you meet and how did the relationship bring you here?

EI: I met Emeka first in 2009, in the company of Qudus Onikeku, Sokari Ekine, Dominique Malaquais, Tèmítáyọ̀ Amogunlà, and others. A workshop on contemporary African dance criticism—actually that was my introduction to art writing. It was a quick meeting. But in 2011 I wrote to him again, asking if I could participate in the road trip of that year. He thought I was a good fit. Our relationship has been part-friendship and part-collaboration. Emeka is very important to my trajectory as a writer. I credit him as one of those who is teaching me to see.

EI: I met Emeka first in 2009, in the company of Qudus Onikeku, Sokari Ekine, Dominique Malaquais, Tèmítáyọ̀ Amogunlà, and others. A workshop on contemporary African dance criticism—actually that was my introduction to art writing. It was a quick meeting. But in 2011 I wrote to him again, asking if I could participate in the road trip of that year. He thought I was a good fit. Our relationship has been part-friendship and part-collaboration. Emeka is very important to my trajectory as a writer. I credit him as one of those who is teaching me to see.

EO: In addition to Emmanuel’s answer above, I would add that from the onset, I have always seen in Emmanuel the future of critical writing from a Nigerian and African perspective. His trajectory (and indeed the man himself) is representative of this needful hybrid between the literary world and that of art criticism. Over the years, we have learnt to tap into our affinity for understanding imagery and its possibilities, our quest to find a new voice inspired by our everyday realities. On the other hand, he reminds me of my vigour when I was younger – with the added incentive of his much calmer constructive temperament.

Let me ask you, Emeka, as the founder of the project. What started this whole idea of traveling around the world and documenting stories? How long did it take to mature from the early stages to where it is now?

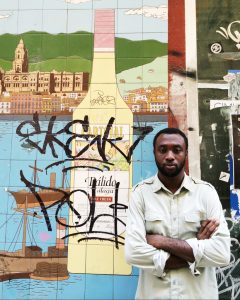

Emeka Okereke

Emeka OkerekeEO: I have always been of the belief that there is no life without movement – there you go, my personal philosophy summarized in one sentence. Growing up, I lived a life whereby the only way I could find solace was in the conviction that life is full of unimaginable possibilities, that it is not as rigid as a singular story. The best thing that happened to me therefore was to become an artist, with the only limitation to my self-expression being my medium, my thinking and the art world! Invisible Borders came therefore out of that belief in perpetual movement to escape stagnation.

The more I delve into the history of Africa, the more I realise it’s a history of an incredibly mobile energetic people stifled by the advent of imperialism and Occidental hegemony. After so many centuries of oppression and suppression, of defining Africa only by her limitations, such projects as Invisible Borders propose that we readjust our mindset and perspective to that which breaks away from an enclosed definition of who we are, and harness the positive attributes of our diversity to create hybrids of multifarious forms of existence. This is what we mean when we say Africa is the future. But how do we attain this future when we are so divided amongst ourselves? Therefore the work begins with a Trans-African exchange.

Travelling, especially around Africa, has presented a surprising amount of challenges. You’d be surprised at how more expensive it is to go to Kenya than to go to London. Travelling by road is even worse, with visible borders, bureaucracies, security challenges, and all. How do you hope that this project changes things for the better?

EO: The most urgent need beyond how expensive or cumbersome it is to travel is to get people to imbibe the perception and attitude of Trans-African exchange. I believe that with this as the foremost, the challenges will be met. We are basically talking economics here with most of the practical and logistical concerns. We have in the past emphasised on the actual infrastructure – the Trans-African highways, the indispensability of road as a tangible conduit and facilitator of this exchange much the same as the artistic interventions. Over the past year, we have seen how our project has inspired many other Road Trip endeavours across Africa. Just recently, a group of Nigerian artists took to the Road, from Lagos to Dakar sponsored by the Goethe Institut Nigeria. Besides it being glaring that this project was modelled after the Invisible Borders project, it is a route we have travelled in 2010. Such projects and many more is an indication that our work is impactful. We shall keep at it for a very long time, and until we have inspired the many agents of change – the artists, cultural administrators, and individuals – in the course of this century.

I have known you, Emmanuel, as a fiction writer and publisher (and later as an art critic). But somewhere in-between, you became a travel writer as well. Could you enlighten me about the transition (or the epiphany, as the case may be)?

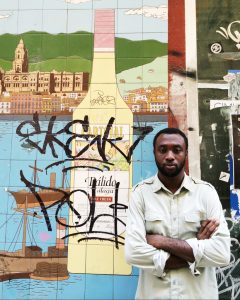

Emmanuel Iduma

Emmanuel IdumaEI: There is a rich twilight between those forms, at least for me. A lot of my work depends on restlessness, or what I fancifully call peripeteia. The idea for me is to constantly think of what’s possible in my writing, and to put the essayist in me in conversation with the novelist in me. I have been thinking a lot about two statements. One is what Barthes wrote: “A critic should be a novelist in disguise.” The other is something one of my heroes said to me: “Crystallize your vision as a writer in such a way that it becomes ennobling and edifying for others.”

I like the liminality you propose. “Somewhere in-between, I became a travel writer.” But to be honest, I have not yet considered the idea of working in mainstream travel writing. I haven’t been able to match my ambition for my travel recollections with the form of more traditional travel writing. In my recent writing, especially after the road trips, the way I remember the journeys is not linear. There’s no narrative arc. It’s like a dog sniffing a field. Dogs don’t follow a straight line. They follow their noses and go all over the place.

So, yeah, the transition isn’t complete.

Travel is a fascinating enterprise. I remember talking to you about joining one of these trips (I believe it was the one of two or three years ago). But travel is also quite a physically and mentally tasking experience, needing 100% of attention and dedication. What interests you, both, in this experience, and what have you gained the most from past editions?

EI: After each trip I usually swear I won’t participate in the next one. My friends are quick to mock how easily I renege on that promise. I want to constantly go afield. The idea of being a stranger in a place, scarcely having the audacity and permission to relate with locals, fascinates me. I mean, much of our travels have been in Francophone Africa. And I can’t make a sentence in French, or Wolof, or Bambara, or Moghrebi Arabic. What does that incommunicability allow? What does it eclipse? This is why I haven’t been able to say no to traveling more with Invisible Borders. The other reason: I can’t separate art from art-making. I can’t distinguish what the head imagines and what the hand does. To see real bodies struggle with art-making, as a writer interested in images, is a gift.

EO: I think for me, it’s about the notion of constantly inhabiting a space of transition, the Middle Ground like Chinua Achebe called it. He went on to explain this as “where everything is allowed to play a role in coexistence, and whatever cannot survive this space is expunged by the same process by which they became a part of it. It is the process by which foreground and background comes into being; it is the core of social formation”. The Invisible Borders is exactly this space or distance of transition sandwiched between preconceived notions and freshly acquired perceptions, between mystery and meaning. Over the past five years we have constantly inhabited this space, and by that generated reflections which to my belief are useful aberrations to the prevalent African narrative. It is a highly charged creative space – I think this is what keeps pulling us back to it.

EO: I think for me, it’s about the notion of constantly inhabiting a space of transition, the Middle Ground like Chinua Achebe called it. He went on to explain this as “where everything is allowed to play a role in coexistence, and whatever cannot survive this space is expunged by the same process by which they became a part of it. It is the process by which foreground and background comes into being; it is the core of social formation”. The Invisible Borders is exactly this space or distance of transition sandwiched between preconceived notions and freshly acquired perceptions, between mystery and meaning. Over the past five years we have constantly inhabited this space, and by that generated reflections which to my belief are useful aberrations to the prevalent African narrative. It is a highly charged creative space – I think this is what keeps pulling us back to it.

Specifically, which ones of the earlier editions of this road trip delighted you the most and why?

EI: My first, in late 2011. There was something valuable about my naiveté, and the fact that a lot of the clarity I’m now gaining about my work wasn’t available to me then. Also, I was traveling out of Nigeria for the first time.

EO: The first impression is always the best! So I will say the 2009 edition. But in the way of valuable experience, I will go for the 2014 from Lagos to Sarajevo. After that trip, I feel invincible, there is really nothing we can’t do!

How did you choose the participants in this edition, and what do you look forward to the most?

EO: It has always been the norm since 2011 to make an open call. But this year, we thought it wise and more effective to go by internal research and handpick certain artists whose work we have been following. We always try to experiment with the different kind of artists we bring on board. This year we have gone with a lot of young and budding artists because we try to position the reflections around the Nigerian Road Trip in the frame of the present/future generation, it is really a project that looks at the future. But again, we are focusing very much on the history of how Nigeria came to be. You understand that we cannot talk about the future of Nigeria in detachment from history because history is the ground under our feet.

If I speak with any of the currently selected participants, what do you think would be their responses to a question like “What is your biggest fear about this trip?”

EO: It’s simple: going to the North from the South. And this fear has a history. Today, it’s due to the violence from Boko Haram, but it all began with that Amalgamation in 1914. Since this time caution has always preceded the South-North transitioning. But we are Nigerians, and off we go!

EO: It’s simple: going to the North from the South. And this fear has a history. Today, it’s due to the violence from Boko Haram, but it all began with that Amalgamation in 1914. Since this time caution has always preceded the South-North transitioning. But we are Nigerians, and off we go!

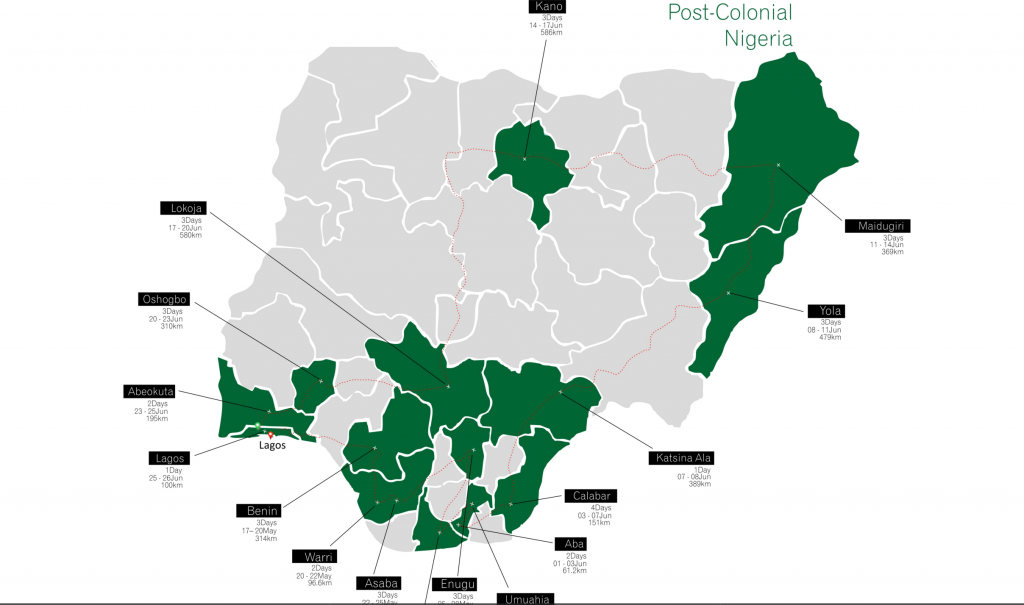

The trip, the poster says, will go from Lagos to the South-South, then northwards through the heart of one of the most dangerous parts of Nigeria in 2016. What are you hoping to find out, and how do you think the findings would impact on the public?

EI: How about we investigate what makes the northeast dangerous? The lives inscribed within this danger, what do they look like? I am constantly aware that Nigeria as we know it, from the time of its naming until now, is constructed. So we know as little as we have been told. This is not to say Maiduguri is a safe place, or Enugu for that matter. For this trip we’re outdistancing the stereotypes we’ve been given about northern Nigeria—especially since a number of us have lived mainly in the south. A work of art brings closer what has been kept afar. I am hoping that in this trip we can add our voice to the chorus of all that is sublime and nuanced, and even paradoxical, about Nigeria. There’s a great sentence in Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior, now framed in my mind: “I learned to make my mind large, as the universe is large, so that there is room for paradoxes.”

EO: Emmanuel nailed it. there couldn’t have been a more perfect answer!

Emeka, as a photographer, and Emmanuel as an art critic and writer, what do you, individually, look for when you walk through a crowd of people, particularly in a place you’ve never been before? What images gives you the most feeling of ‘this is highly significant!”

EI: I’ll go back to the image of a dog sniffing a field, which is a metaphor Tacita Dean uses in relation to her research method, quoting the great Sebald. “You allow yourself to be interrupted on your journey and led elsewhere by whatever you encounter,” she said. I believe in this very much. If an art critic must be as intelligent as possible, that intelligence is ultimately the possibility of testing the fitness of my instincts. I learn a lot from the language of improvisational dancers, especially those who allow the energy of an audience shape their movement on stage. This is a roundabout way of saying I have a vague sense of what to look for when I walk in a crowd as a stranger. My goal is to forget my assumptions. To listen.

EI: I’ll go back to the image of a dog sniffing a field, which is a metaphor Tacita Dean uses in relation to her research method, quoting the great Sebald. “You allow yourself to be interrupted on your journey and led elsewhere by whatever you encounter,” she said. I believe in this very much. If an art critic must be as intelligent as possible, that intelligence is ultimately the possibility of testing the fitness of my instincts. I learn a lot from the language of improvisational dancers, especially those who allow the energy of an audience shape their movement on stage. This is a roundabout way of saying I have a vague sense of what to look for when I walk in a crowd as a stranger. My goal is to forget my assumptions. To listen.

EO: The image is always a precipitate of a lived experience. Part of preparing myself for the trip is to divorce myself of any idea of an image that I would like to have. There is something funny about images: there is a thin line between an image which limits perception and that which liberates it. Rather than talk of an image, I would reflect on the kind of encounters we hope to make. I look forward to meeting Nigerians from all walks of life – from the farmer, the mechanic, the trader in the market to the business tycoon, politician, advocate of human rights, nurses, doctors, you name them – listen to their unique stories, share their moments with them, learn from our exchange. It is only after then that the camera comes in, to bear witness or emblemize the occasion.

One more question that i’ve always wanted to ask photographers, Emeka, what actually happens to all the images you take over many years? I sometimes look into my records and wonder what I should do with photos taken which at some point meant a lot to me. I assume that many of them are shown at exhibitions. Do you ever duel with yourself as to which to keep and which not to, which to exhibit and which not to? What helps you in making those decisions?

EO: We are all asking ourselves the same question. Especially at a time of digital proliferation of images. Selection of images is part of the daunting process of image making, so it comes with the profession. Beyond that, the biggest challenge at the moment is figuring out methods of archiving. I have always said that for every click we make in and about the African continent, history is made. So while we meticulously chose images for exhibitions and presentations after the road trip project, we throw nothing into the bin. We always thinking of posterity, some of these images need to age – like fine wine.

How can the public help this trip?

EO: We have reached out to the public, asking for their contribution in the way of knowledge about the historic and contemporary narratives of the states, cities and regions we are scheduled to visit. We really want this project to be about profound encounters, and doing so through assistance of well-meaning indigenes of these places is the most productive way to go.

What should we look forward to at the end?

EI: A solid amount of images, film, and writing. A body of work from each of the participants. Because there’s so much to make sense of in Nigeria, I don’t think there will be an excess of responses.

End

__________

Still to come: interview with other participants in the road trip.

__________

Photos from OkayAfrica, CNN, and Google Images.

“The entries were handed over to the panel of judges by the Emeritus Professor Ayo Banjo Advisory Board for Literature. Other members of the Advisory Board are Emeritus Professor Ben Elugbe and Professor Jerry Agada. The panel of judges is led by Professor Dan Izevbaye, a professor of English Language, at Bowen University, Iwo. Other members of the panel of judges include Professor Asabe Usman Kabir, Professor of Oral and African Literatures at Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto and Professor Isidore Diala, a professor of African Literature at Imo State University, Owerri and first winner of the award for Literary Criticism. The International Consultant is Professor Kojo Senanu, Professor of English at the University of Legon.