Introduction

While the formal fact-finding panels pursue their assignment, and bewildered minds attempt to absorb the turn of events, reflect upon, and engage in informal caucuses on ‘what really happened’ during, and following the authentic #ENDSARS campaign, both in the Lekki arena and in horrifying dimensions across the nation, I believe that it will not be out of place to offer a parable extracted from a forthcoming work of fiction. A parable, yes, but an actuality that has become virtually institutionalized across the nation. It is offered as a public service before the events of the month of October 20/20 congeal in the minds of participants, onlookers and consumers of the Nigerian staple of the now mandatory UFN (Unidentified Flying Narratives).

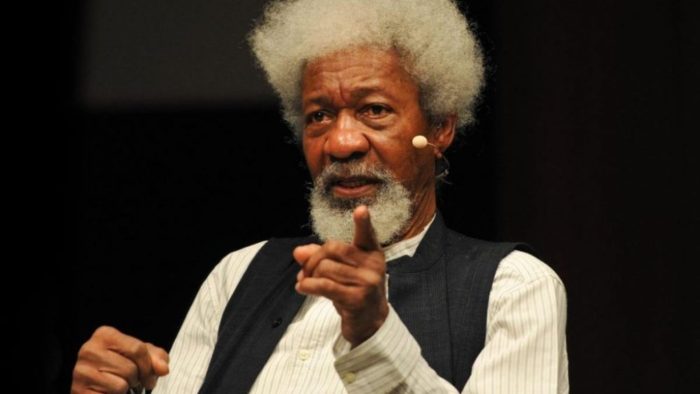

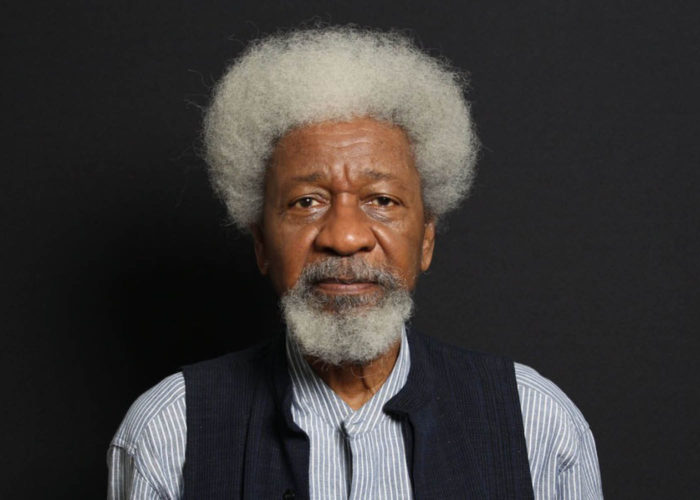

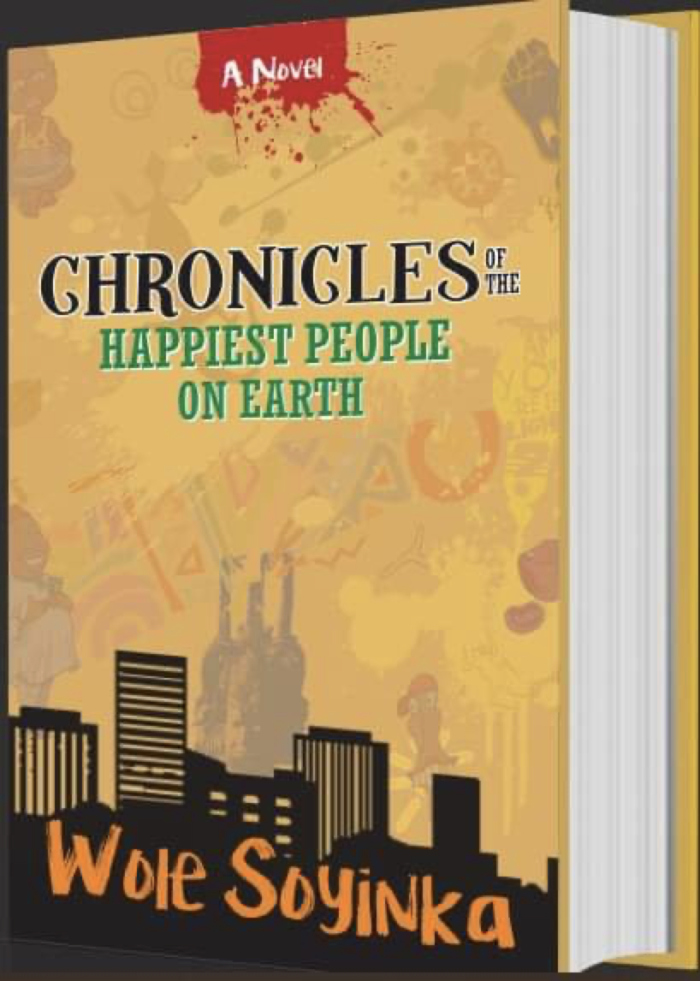

The forthcoming novel from which it is extracted — CHRONICLES FROM THE LAND OF THE HAPPIEST PEOPLE IN THE WORLD (BookCraft) – will be published towards the end of the month of November, 2020. – Wọlé Ṣóyínká

Read on:

Excerpt from CHRONICLES

Adjusting to a new culture was his main concern, but not an insurmountable culture shock. Badagry, after all, albeit closely intertwined with Lagos, was still Badagry. Pitan-Payne was on hand, though keeping a frenetic pace to wind up his affairs and proceed to his UN assignment on schedule. The engineer seemed to thrive on interlocking calendars, and in any case, he now had Menka to pick up the loose ends for him in his absence….

The timing could not have been more thoughtfully ordained. The unexpected and the planned seemed to dovetail neatly, like the finely adjusted sprockets or his mechanical prototypes. And while Lagos/Badagry lacked the excitement of receiving sudden cartloads of human debris from Boko Haram’s latest efforts to out-Allah Allah in their own image, one could count on gratuitous equivalents from multiple directions. Such as the near daily explosion of a petroleum tanker on the expressway or city centre. Or a roofless lorry bulging with cattle and humans tipping over on a bridge and dropping several feet onto an obliging rock outcrop in the midst of the river. Sometimes, more parsimoniously, a victim of military amour propre – in uniform or mufti, it made no difference. That class seemed to believe in safety in numbers, and all it took was that even a low-ranking sergeant should take offence at another motorist, who perhaps refused to give way to his car, a mere ‘bloody civilian’, never mind that the latter had the right of way. An on-the-spot educational measure was mandated. Guns bristling, his accompanying detail, trained to obey even the command of a mere twitch of the lip, leapt out of their escort vehicle, dragged out the hapless driver, unbuckled their studded belts, whipped him senseless, threw him in the car boot or on the floor of the escort van and took him to their barracks for further instruction. However, the wretch sometimes created a problem by suffocating en route – which left society to develop structures for neutralizing such inconvenience.

The contradicting, ironic sequence occurred to Menka only for the first time – yes, come to think of it, the military hardly ever recorded a fatality – once or twice, maybe even three times in a month — yes, the accident of excess did happen, but mostly such terminal disposal was left to the police, whose favourite execution site was a road block, legal or moonlighting. Perhaps a recalcitrant commuter, or passenger bus driver had refused to collaborate in providing a bribe on demand, or insulted the rank of the demanding officer with a derisive sum. And it did not have to be the original offender but some too-know grammar spouting public defender who had intervened on behalf of the potential source of extortion. The outcome was predictable – victim or good Samaritan advocate instantly joined the statistics of the fallen from ‘accidental discharge’. The expression was still current, but often it was anything but. Accidents had become infrequent and unfashionable. Oftener to be expected was that the frustrated, froth-lipped police pointed the gun, calmly, deliberately, at the head of the unbelieving statistic and, pulled the trigger. Again, the inconvenience of body disposal.

But then, the community of victims themselves – what a specialized breed of the species! The roles, it constantly appeared, had become gleefully, compulsively interchangeable. Allowing him only a few days to ‘catch your breath and get your bearings’, Pitan-Payne lost no time in taking Menka to inspect the land designated for the Gumchi Rehabilitation Centre, for victims of Boko Haram, ISWAP and other redeemers – nothing like striking while the iron was hot! On their way, the familiar sight of crowd agitation – how would the day justify itself without some kind of street eruption somewhere, wherever! Trapped in the chug-stop-chug of traffic, the favourite commuter distraction was to attempt to guess what was the cause, and even place bets on propositions. That morning, Menka’s first in nearly a year down south did not disappoint. But for the milling blockage by intervening viewers, they could have claimed the privilege of ringside seats. Compensating for that obstructed viewing however was the sight of men and women trotting gaily, anticipation all over their faces, towards the surrounded spot of attraction. From every direction they came, some vaulting over car bonnets, squishing their legs against the fenders, squeezing through earlier arrived bodies or simply scrabbling for discovered vantage viewing points. They climbed on parked vehicles and the raised concrete median. Commuter buses slowed down and stopped, keke napep — the motor-cycle taxis — pulled aside, drivers and passengers alike rubber necking on both sides of, or in the direction of a wide gutter that sank into a culvert. The lights changed to green and Pitan-Payne drove on, their last shared image a pair of muscular arms raised above the bobbing heads, clutching an outsize stone, slamming that object downwards into the gutter. Very likely a snake, Pitan suggested. With the rainy season, quite a few sneaked through the marshes into culverts and slithered their way into parking lots and even offices.

A police van came racing down the road, against the traffic, strobes flashing and sirens blaring, so Menka looked back, saw the crowd drawing back and drifting reluctantly away from the uniformed spoilsports. This opened an avenue just in time for Menka to obtain the briefest glimpse of an object slumped over the rim of the gutter, once human, but not any longer. Indeed the only human identity left him was his iodine-red tunic and black trousers, still recognizable as the uniform of a LASA officer, an unarmed unit whose function was simply to unplug traffic – stoppered as readily by truculent drivers as by the roadside markets, vendors of all the world commodities who had taken over the streets, haggled, negotiated, delivered change and goods at their own pace. If the activities delayed movement over half a dozen changes from red to green and back again, it did not concern them in the least.

Later that evening, the television newscast narrated the full story. After futile spurts of preventive measures, Authority had commenced arrests of vendors and seizures of their wares. The LASA team, their van parked in a side street, had pursued several such malfeasants. In a desperate attempt to escape capture however, one ran straight into the snout of a speeding vehicle, was tossed up, landed with an ominous thud on the sidewalk and remained there, unmoving. In a trice, a mob had gathered. They set the parked LASA vehicle on fire and worked up further appetite for vengeance. The unarmed officers had already fled. A hunt party pursued and eventually brought down a scapegoat, quite some distance from the actual scene of crime. They proceeded to the ritual battering of their catch. He broke free, ran into the gutter, tried crawling into the culvert for safety. They dragged him out by his feet, trunk and head smeared and reeking from the accumulated sludge of the blocked tunnel. Passers-by, totally ignorant of the beginning or mid-act of the mayhem, refused to be left out. They grabbed the nearest assault weapon to hand and joined in the gratification of the thrill for the day, a newbreed citizen phenomenon. The massive stone, raised above a throng of heads, quivered lightly against a Lagosian skyline of ultra-modern skyscrapers before its descent onto bone and brain. It took on an iconic dimension that stuck instantly to Menka’s surgical album of retentions, a rampant insignia of the transfiguration of a collective psyche.

“I envy you” Menka remarked the following morning, as they confronted the print media coverage, their scalding coffee no match for the nausea aroused by the photograph sensationally smeared across the front page. “You are going away for a while. You’ll be spared such sights.”

“I feel guilty”. confessed Duyole. “Guilty, but yes, that is one spectacle I shall not miss.”

“Careful!” Menka quickly cautioned. They have their equivalents over there. Ask the black population.”

“No. Not like this. Occasionally yes, there does erupt a Rodney King scenario. Or a fascistic spree of ‘I can’t breathe’. America is a product of slave culture, prosperity as the reward of racist cruelty. This is different. This – let me confess – reaches into – a word I would rather avoid but can’t – soul. It challenges the collective notion of soul. Something is broken. Beyond race. Outside colour or history. Something has cracked. Can’t be put back together.” And then Pitan-Payne gasped, paused, folded over the pages and passed the newspaper to Menka. “Take a look at this. Not that it changes anything but – here, read it yourself.”

There was a chastening coda. It altered nothing. The fleeing vendor, whom no one had even thought to help, was very much alive. He had picked himself up, salvaged most of his scattered goods, and found his way home despite a sprained ankle and some bruises. Most of the earlier spectators had retreated to a safe distance. They continued what they had been doing earlier – filming the action with their phone cameras. The police did however capture the Goliath with the terminating stone who had administered the coup de grace. He remained on the spot, to all appearance, admiring the evidence of his work.

He vehemently protested the injustice of his arrest: “I thought he was an armed robber.”

The END.