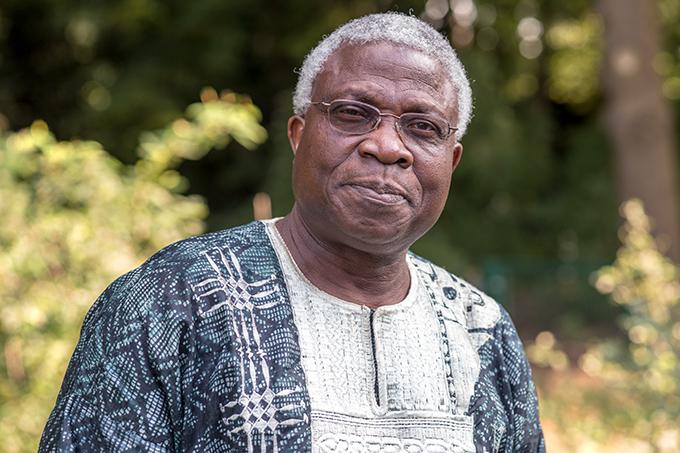

by Ọlájídé Sàláwù

Everyone always hoped that January should end. I myself strongly felt it should. The Ides of January are its long tentacles, the sprawl of days, the cheesy Harmattan wind, the dry pocket after the Christmas shopping spree, the lurch for lights after the previous brackish year, and the hope for a new clearer sky. If one looked at it closely in the grand scheme of things, one would always find a reason to want January to end. My savings, for example, were already going down the drain and I was expecting that new stipend would come in soon so as to restock foods before I resumed teaching fully. But, it seemed each day was always getting stretched and there were invisible decimals of hours that kept kneading the month longer than July or August or every other month that has the same almanac of days.

While one felt that January should end because of its potential dryness at least after vacation loss of December, it set one into the New Year race. After all, in Pentecostal Nigeria and the litany of other orthodox churches from where I came to America on Fulbright scholarship, so many wars and battles are fought on “the crossover night.” At the turn of every year, the seers come with their prophecies: some gloom and others bloom. Once upon a time, a Nigerian President had this great vision for the country’s success tagged Vision 2020 for a new Nigeria. He would be fascinated to learn that the country is the same hell-hole he left behind.

The hankerings over 2020 have been in the loop for long. Like all Januaries, this year’s was filled with so many excitement for me. I would be interacting with my students in person for the first time. The bulk of my work in the previous semester was more of workshops within the University environment and in neighbouring colleges. And I had a thought: This semester, I have got much to get ready for you. Back in Janus-faced Babylon, things were the same and everyone cared less about the organisms incubating in Wuhan, China, and the President had even shooed it off as the flu.

I spent my last winter holiday under the frosty arms of Winnipeg, Canada which was colder than Fayetteville considering it is northernmost in terms of closeness to the Pole. I returned when the month had just broken in the middle and the teaching schedule would commence albeit reluctantly in the following week I arrived. Ten students had already enrolled for the class by the end of Fall. That was in November. On my arrival to Fayetteville, my body still failed to adjust to the weather. Although I had never witnessed a snowy Fayetteville, Winnipeg on the other hand was often white-laced and the heavens were always on the low temp.

I continued to put on my thermal wear to absorb the frigid wind that came with the morning, vamoosed in the afternoon sometimes, and returned arrow-faced in the night. I also threw on my black overall jacket to keep my body safe after the cream-colored thermal underlay. Sometimes, I got layered like onions with more clothes after the thermal dress to wrest myself from the bristling wind of Cumberland where Fayetteville is located. Fayetteville is not always like that.

In the last week of January, classes began proper and the first two classes I had with my students were tellingly diverse. Five of my students were African Americans, the others have by chance of migration of grandparents became citizens of Babylon. The senior professor, a Nigerian-American, who I was co-teaching the class with was also from Ògbómọ̀shọ́, Nigeria, and was part of the brain drain wave of the ‘90s when he embarked on a doctoral program at the University of Florida. His rich knowledge of the culture even after decades of exiting Nigeria amazed me. Well, even if everybody is leaving Nigeria’s hell, there is so much that people hold on tightly to. It is the culture. It is the language. The food! And then, this is a course he has been handling for years.

We had a fair outline in the syllabus to work with that did not only emphasize the communication aspect of Yorùbá language, but also the culture. I would be handling the cultural aspects while the professor would handle the language part, at least for the first few weeks of the semester. Our classes would be held in two different buildings on campus. The Monday and Wednesday classes would hold in one of the rooms at Science Taylor Building while the Friday classes held at Butler Building. The first Monday class was getting the students a Yorùbá identity. So I suggested that the students should check Yoruba Name portal where they could find the name of their choice and also acquaint themselves with the meaning. The following class, they came back with interesting names such as Ayọkù, Jádesími, and Ọrẹolúwa.

That was the first part of the introductory class. We have also instructed them that searching for the names on the website is not compulsory and they could look at circumstances surrounding their births to decide the names they would like to bear during the class. On the first week of February, they all returned with a paragraph on the story surrounding their names. Tatyana had picked the name ‘Odáyàtọ̀’. She claimed she is a unique child in her family. After this introductory week, the class was settled on a slow cruise. In America, the students are kings with a hunch of debt breathing behind their backs. You have to appeal to them how attending classes and seminars related to the course would earn them credits. So I had to re-learn my tolerance in new way and then send the classroom culture which I had imbibed back Nigeria packing.

At the beginning of February, the story of an ultra-modern hospital built in ten days in Wuhan jarred the world into a bit of consciousness. Most of the media began to place the news of the virus in their headlines. There was a gush of conspiracy theories also flowing from all sides of the world.

At this time, there hadn’t been any announcement in the University on the imminent gloom. As the countries around the world started closing their borders and economy started shutting down, people waltzed bare-nosed into Walmart in Fayetteville. The atmosphere on campus was taken by the faint gossip on the virus but students still loiter around Ecoground Café where I did relaxed with the smell of Starbucks coffee wafting into my nose. As expected, I myself was getting thrilled as my students were beginning to master the Yorùbá greetings, especially the ‘Kú’ greeting. The most enthusiastic among them, Cevyn, was fond of asking me Báwo ni before following that up with Ẹ káàsán o since the classes often held in the afternoon.

Then one day, the University Clinic sent for Yan, the Chinese lady who was also a Foreign Language Teaching Assistant. She was in the office with me when she got the notice that she had to report at the University Clinic for a routine medical check. In December during Fall break, Yan had travelled to Harbin in China to spend her holiday. Although the population of the infected persons in China then was a few thousands and Harbin where Yan had come from was not a hotspot for the spread of the virus, such travel was considered high risk and the University demanded she report herself that morning. During the break, I was away in Canada and there was little or no impact of the pandemic around December and the first two weeks of January when I was there. Whereas Houcien, the Moroccan FLTA who was teaching Arabic, turned her sight towards Grand Canyon and later spent few days in Los Angeles.

For the semester I was auditing two courses. So ordinarily my weekdays were filled up. In this shuttling, I moved to attend Dr. Murray’s African-American Literature classes and Dr. Bir’s editing and proofreading classes. But since these two were audited courses and not meant for credit, I often leaned on that fact and played truancy while giving more attention to my primary duty. Of course, we had a great plan ahead of us. There was the Global Awareness Day which I had to prepare the students for, and we were already considering scrapping Wednesday’s class for the rehearsal of the songs the students would sing. Besides, I was scheduling a social evening events. One would be for watching Yorùbá film, say Ṣawaoro-Idẹ and the other to listen to Yorùbá songs. There we would also have some local Yorùbá snacks such as ọ̀jọ̀jọ̀! I handled our second class of the last week of February and introduced the students to musical instruments in traditional Yorùbá society. It was their first time they would see the talking drum.

The momentum the virus gained at the beginning of March meant things would go awry sooner or later. Nobody knew where the wave of the virus would move to, but North Carolina had caught a bit of the sneeze via a patient at Wake County. News of class transition had started to breeze in. I carried on with my preparation for the Global Awareness Day, teaching the students the common Yorùbá songs, “Fún Àlááfíà” and “Isẹ́ Àgbẹ̀”. Their pace of learning the songs awed me, and by the second week of March when we had our rehearsal, I added “Eleketo” as the third song. Though the last song was a bit difficult for them as they were yet to grapple with the tonal glides in-between the stanzas. The other aspect of the class had fared well as well. We have moved on from greeting. They can now all read the Yorùbá Alphabet and thankfully memorize some good, fine social gestures.

Things quickly went down south as March approached its end. The University announced that all classes should proceed online and office hours of instructors would take place at an upswing. It was unsurprising considering that the United States declared that all international borders would close. The campus was shut down, save for the faculty should they have some office work to round off before complete closure. So puff went the Global Awareness Day and social evening events which already got the students. I already thought our classes would move to Zoom or Blackboard as other universities were now using these platforms. Few friends at other Universities, who also came from Nigeria on the Fulbright program, were already scheduling synchronous methods. Professor Àjàní told me that I would be completing the other side of my teaching duty by interacting with students on Canvass while he would shoot videos for the rest of the topics on the syllabus at the University’s digital lab.

On the first week of April, the University Place Apartment came in. We were meant to vacate the residence as all students were issued instruction until the end of March to leave. Drey and Mark, the two black American students, who I and Houcien shared the apartment with moved out as well. Gracefully, an extension was secured for all the FLTAs, for two weeks, by our administrative supervisor, Dr Sharmila. When it was a week before the extension deadline, I asked her what the plan for our last accommodation would be and she replied we might likely to be moved to a hotel, Extended Stay.

On the first Wednesday of April, we received final notification from the Hall Life Management that we have until 12th of April to leave. April had visibly held Spring in sight. The Carolina originals were already shooting out their beauty. The sight of the azaleas and Japanese Maple Tree was alluring. But what also sprang forth was gory news around the world about the virus devastating the landscape. I wrote to my supervisor about the Extended Stay Hotel. She quipped I should not worry, the University would be moving us into an emergency hall on campus called Renaissance.

And so, the story began. April was the cruelest month.