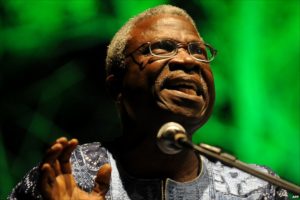

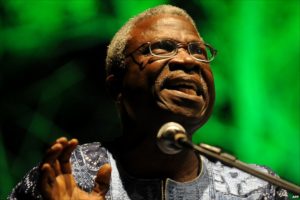

P rofessor Níyì Ọsundáre is Professor of English at University of New Orleans, USA, and one of the best-known poets from Africa. His works of published poetry include Songs of the Marketplace (1983), Village Voices (1984), A Nib in the Pond(1986), The Eye of the Earth (1986), which won both the Association of Nigerian Authors Poetry Prize and The Commonwealth Poetry Prize in its year of publication. He was also a recipient of the prestigious Folon/Nichols Award for ‘excellence in literary creativity combined with significant contributions to Human Rights in Africa’. Other published volumes of poetry include Songs of the Season (1987), Moonsongs (1988), Waiting Laughters (1990), Selected Poems (1992), Midlife (1993), The Word is an Egg (2000) and Tender Moments(2006). Niyi Osundare has also published four plays and essays on literature, politics and culture. Orality and performance are important features of his works, which have been translated into the Italian, French, Dutch, Czech, Slovenian, and Korean languages.

rofessor Níyì Ọsundáre is Professor of English at University of New Orleans, USA, and one of the best-known poets from Africa. His works of published poetry include Songs of the Marketplace (1983), Village Voices (1984), A Nib in the Pond(1986), The Eye of the Earth (1986), which won both the Association of Nigerian Authors Poetry Prize and The Commonwealth Poetry Prize in its year of publication. He was also a recipient of the prestigious Folon/Nichols Award for ‘excellence in literary creativity combined with significant contributions to Human Rights in Africa’. Other published volumes of poetry include Songs of the Season (1987), Moonsongs (1988), Waiting Laughters (1990), Selected Poems (1992), Midlife (1993), The Word is an Egg (2000) and Tender Moments(2006). Niyi Osundare has also published four plays and essays on literature, politics and culture. Orality and performance are important features of his works, which have been translated into the Italian, French, Dutch, Czech, Slovenian, and Korean languages.

________

Thank you for talking to me. And congrats on your 2014 National Merit Award.

I should be the one thanking you for providing the forum, for making it possible for this exchange to take place.

Let’s start with your poetry for which you’ve been widely acclaimed. The last recorded work from you was in 2006, titled “Tender Moments”. Is there a reason you haven’t released another published collection since then, almost a decade ago?

Tender Moments is, actually, not my last publication. The book has got two aburos: City Without People: the Katrina Poems, published here in the US, and Random Blues, the first volume of the collection of my weekly poetry column in the Sunday Tribune. Both were published in 2011. And right now, the publisher is looking at a new book of poems, some kind of travelogue-in-verse, which I completed last year after many years of preparation. I’m also working on a sequel to The Eye of the Earth, a 1986 book whose resonance and thrust I consider so achingly relevant in this age of the deniers of the scourge of climate change and global warming, even when the effects are so palpably, so tragically evident. Many of the poems from this manuscript have featured in three influential international journals on either side of the Atlantic: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and the Environment (ISLE), University of Oklahoma’s World Literature Today, and Moving Worlds of the University of Leeds, UK . Mine were invited contributions, and I am both glad and inspired by these journals’ single-minded concern with some of the burning issues (all pun intended) of our time: nature, climate change, wild winds and tsunamis, etc. So, you can see I’ve not been sleeping on duty!

I first met you on the campus of the University of Ibadan where you taught in the department of English, and then left for New Orleans. What was your most significant memory of teaching in Nigeria compared to teaching in the United States?

Now, you’re asking me to cast in the past tense a narrative that is still very much in the present tense. My pedagogical and academic relationship with the University of Ibadan (and other Nigerian universities) continues, though at a less formal, less regimented level than before. You will remember that I said in my 2004 valedictory lecture that my relationship with the University of Ibadan is a laelae (lifelong, everlasting ) affair. This is why I do not come on the summer vacation without having one kind of interactive session or another with students in the Department of English – a mutually beneficial activity which I thank the present Head of Department for facilitating. I also actively participate in academic events in other departments. But I do know that both the tenure and the tenor of my service have changed, and things are not exactly where they were when I left in 1997.

Now, teaching at Ibadan versus teaching at the University of New Orleans. Many similarities and a few differences. To begin with, in both institutions, I have to deal with students, the centre of my professional concern. I have discovered that students are virtually the same everywhere: young, vulnerable, unsure, even fearful, but inquisitive, ambitious, demanding, generally idealistic. And on both sides students who are sharp as razor, engaging, and quick on the uptake, and those who are a little slow and need some gentle prodding. But what makes the real difference is the environment. It is common knowledge that the Nigerian student as well as her/his teacher are still engaged in a life-or-death struggle for the provision of amenities which their American counterparts have come to take for granted: steady power supply, potable water, relative freedom from hunger and suchlike harassment by social needs, a predictable academic programming and scheduling, and above all, a relatively stable political system. A book comes out on Monday; by Thursday it is already within your grasp; access to internet facilities that are fast and inexpensive. These are facilities still far from the grasp of the Nigerian student. But in a way there is some ‘sweet uses’ to the Nigerian’s student’s ‘adversity’ – to echo Shakespeare. Driven by need and necessity, the Nigerian student tends to be more aggressive, less complacent, and less dependent (Who are you going to depend on: parents who are barely striving to survive, or a government that has no interest in your welfare?). I have observed that drop-out rate is much, much lower among Nigerian undergraduates; for to drop out is to drop under and, in many cases, to drop dead; for the kind of socio-economic safety nets available to American students are nowhere there for their Nigerian counterparts.

At the faculty level, surely, the American academic has much more to work with: the laboratories are well equipped and functional, research funds are made available (depending on the buoyancy of the university’s budget; for, yes, even in America, colleges and universities do go broke!). As a result of a situation of general relative contentment, labour union activity is almost non-existent in American Academe. Many times I miss the rousing militancy of ASUU!

You were notably affected by Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005, and you’ve given a number of interviews about that sad event. Do you hope to write a memoir about it at some point? Many of us would like to read what it was like to get through those harrowing times.

Thank you for your concern. The book mentioned earlier on in this interview, City Without People: The Katrina Poems, has tried to explore and articulate some of the harrowing experiences. The poems themselves are sandwiched between two prose pieces: a prose preface and an interview both of which put the Katrina narrative in proper perspective. But there was a prose parallel I was writing while composing the poems. Somehow, I managed to complete the book of poems, but the prose narrative stopped a few pages after 40. The memory of our losses weighed me down. The prose narrative literally collapsed under the debris. Why and how I found poetry a readier bearer of the tragic experiences, I still do not know. I think this would be an interesting study for psychanalysts. Even the poems, I couldn’t complete until six years after the hurricane… I may go back to that prose narrative someday – maybe when I’ve retired from this penny-a-day teaching job and I have more free time to myself. And when the trauma engendered by memory of the event would have thinned out sufficiently to allow for relatively painless recollection. But then, who knows: some memories never let go of our faculty of remembrance.

Being influenced by your Yorùbá background, you must have strong opinions about poetry as performance (spoken-word) as opposed to poetry as text. How best do you think poetry should be enjoyed or employed?

Both ways, both modes. And more. In the house of poetry and its practice, there are many rooms. Some poems are written for the eye, some for the ear, and others for both. I see my Yorùbá background as abundant blessing to my poetry. I have always wondered what kind of poet I would have been without this fabulously rich culture and its language. Or, indeed, whether I would have been a poet at all. Come to look at it: everything in Yorùbá is poetry-in-motion, poetry-in-action. Yoruba language is music: from its intricate tone-system to its inimitable ideophones. Sounding is meaning, and meaning is sounding. A language whose syllables sound like drumbeats. A generously metaphoric language which can render the most abstract concept in the most arrestingly imagistic way. Compare ‘I am hungry’ with ‘Ebi npa mi’ (Hunger is beating/killing me); ‘I am shy’ with ‘Oju nti mi’ (Eye is pushing me) . This phonological and imagistic paradigms are central to my poetics. For me, the line is not complete until I make it sing and make it sing meaningfully. My Muse is never far from her/his music. Those who cavil at the abundance of repetition in my poetry need to know the music behind my Muse. Fortunately, this is not an exclusively Yoruba attribute. The music of Welsh language drives the prosody of Gerard Manley Hopkins and, to a lesser extent, Dylan Thomas; Irish inflections in the drama of John Millington Synge. How can one come to a full experience of Igbo masquerade chants in the poetry of Obiora Udechukwu and Ezenwa Ohaeto; of udje songs in Tanure Ojaide, without remembering the haunting musicality of Soyinka’s Death and the King’s Horseman and Osofisan’s The Chatterinng and the Song, the threnodic minstrelsy of JP Clark in Casualties and Song of a Goat? It is this blend of sounding and meaning, music and movement that lies at the heart of the performative strategies and enactive potentialities of the poetry of Akeem Lasisi and Segun Akinlolu (Beautiful Nubia)… At the personal level, I hear my words before I set them down on paper. I allow them to indulge me in the sheer musicality of their essence, their dramatic possibilities. Most times, I see with my ears. For every word I care about, all the world’s a stage.

It’s been said that your decision to resettle in the United States was based on the educational opportunities afforded your daughter who is hearing-impaired. What has been your experience from the time of your resettlement about what’s lacking in Nigeria and what can be done about it?

Thank you for not forgetting this personal dimension. Yes, indeed, my family and I left Nigeria hurriedly in 1997, (leaving behind our son who was then an undergraduate at the University of Ibadan). My wife had to leave her job while I took an unexpected leave of absence from mine. The English Department of the University of New Orleans facilitated our relocation by providing me a job. Upon our arrival in the US our daughter was enrolled in the Louisiana School for the Deaf in Baton Rouge, about one- hour drive from New Orleans where we live. That school provided the necessary educational needs and a conducive environment, and our daughter took full advantage of these and began to thrive. Her talent in Fine Arts was spotted straightaway and fully encouraged. Two years later she was recommended for admission to Gallaudet University, America’s famous university for the deaf, in Washington, DC. where she graduated with a degree in Fine Arts. She is out of school now, still figuring out what to do to earn a living. It’s been a challenging period for all the family, but we are happy this girl has not ended as a roadside beggar in Nigeria. Our experience has shown us all the more how little Nigeria is doing for her citizens, especially those impaired and those with special needs. Ours is not yet a humane society. There is plenty of work to do to get us to achieve that ideal. But we must not relent. Every child deserves the best.

What role do you think that poetry should play in the political and cultural environment in Nigeria and around the continent?

Seven cheers to you for asking this question which many would have considered intolerably old-school, even passé, in our triumphally ‘post-colonial’, post-functionalist, post-humanist condition… Poetry is the soul of a people, their heartbeat, the rhythm of/in their movement, the rhyme in their reason. It is that magic which distills cosmos out of their chaos, the song which salves their sorrow and exults their gladness. It is that oríkì which causes the head to swell; that èébú which makes the victim feel like jumping into a bottomless river. Poetry has never been far from politics, for the real poet is one who holds up the mirror to the naked emperor; one who calls evil by its original name; one who perceives hope where others only see despair. Have I idealized the poet and the role of poetry? Yes, and deliberately so. The poet is no insulated saint nor is s/he an angel. I am inclined to judging life by its possibilities, not its failures; to accept life’s cup as half-full while I join others in finding a way to fill the remaining half.. It is legendary now, the staunch, life-affirming role that poetry has played in African politics, from the anti-colonial, pro-Independence versifying of the Osadebays to the towncrier griotism of the post-Independence era, and the ‘decentred’, ‘indeterminate’ collage of the ‘post-colonial’ present. Has poetry ever caused the toppling of bad governments in Africa? I wouldn’t know for sure; but I do know that excoriative words and guillotine verses have chipped away at the ramparts of despots, military or civilian, opening up fissures and cracks for the entry of revolutionary barbs. As for culture, African poetry keeps reminding the African tree of the neglected importance of its roots, the African society of the pollution of its values.

Literary output in the local languages of Nigeria has been abysmal in the last couple of decades. Why is this so? What can be done to revitalise the industry? Is it even worth it?

Our indigenous languages are in that state because they have been neglected by our government and ignored by our school system – just like other aspects of our culture. The enthusiasm brought to bear on their cultivation and promotion in the 1970’s and 1980’s has fizzled out just as aggressive, and philistine foreign religions have desecrated and taken over the temples and shrines of indigenous deities. Ọmọlará Wood put the matter so succinctly well in her book chat at the First (2013) Ake Book and Arts Festival when she said ‘I think a lot of our ways are demonized, especially in the Nigeria of today where it is perceived to be uncouth to speak your language’. She then sums it all up in this painfully crisp, undeniable statement: ‘Others rubbish our culture because we don’t value it’ (Both quotes from Sunday Tribune, January 13, 2014). We Africans are a people in danger of a looming culturecide. In the southwest, people like Adébáyọ̀ Fálétí and Akínwùmí Iṣọ̀lá have built on the solid foundation of the likes of Fágúnwà and Ọdúnjọ, and produced literary works that are deep and enduring. I shudder to think of what will become of creative writing in Yorùbá when these intrepid cultural and linguistic nationalists are gone. Well, maybe it will be Nollywood to the rescue, though the kind of trivialization and literalization the indigenous languages are going through in the video world are a cause for worry. Needed urgently an educational policy that will make the teaching and study of Nigerian languages compulsory in all Nigerian schools, and a mindset that does not privilege the foreign over the indigenous. Without an iota of doubt, we can only get to that juncture when/if we get our politics right.

How do you see the future of literature in Nigeria? What gives you hope? What gives you despair?

On the positive side: Thronged. Complex. Diverse. Largely relevant

On the not-so-positive, my concern about the increasing diasporization of Nigerian/African literature in conjunction with the phoney globalization which deceives people into the acceptance of a world on whose map their own home is missing. Consider this: Our ‘best sellers’ are determined abroad, in places where the values which propel our imagination are either unknown or disdainfully discounted. Virtually every young Nigerian now dreams of getting published abroad (read USA and Europe). The cultural, socio-economic, and aesthetic repercussions of this exogeneist mentality are grave and far-reaching. Our writers’ charity no longer begins at home. This is culturally and psychologically suicidal. But who can blame these young folks, considering Nigeria’s illiterate, philistine political leadership, our inefficient and dishonest publishing culture and abysmal reading habit, and the consequent slump in the sale of books. We must create an enabling environment that does not alienate Nigerian writers and their vast and diverse talents. For this to happen, again, I say: we need to get our politics right.

____

This interview first appeared in Aké Review 2015

There were many more, not just from the panelists who in a few instances disagreed on the cause of and the solutions to many of the issues. (Is religion a force for good or for ill in these matters? Yes? No? Ayo Sogunro argued, correctly I believe, that our imposition of a foreign belief system on what was a fairly equitable traditional family system complicated our gender relationships and gave excuse to men to relegate women into subservient roles because “the bible said so” or “it’s written in the Qur’an”. Femi Jacobs disagreed, crediting religion with all the good in the world and absolving it of the resulting ill. The followers of the faith, in his opinion, are the ones most responsible for the interpretation of simple harmless injunctions. This isn’t satisfactory, I argued, citing examples in Catholicism where divorce is frowned upon, and Islam where female genital mutilation is – in some cases mandatory. We cannot always separate religion from much of the problems we have with oppression and inequality in marriage, I said. It’s called “Man and Wife”, after all, and not “Husband and Wife”, where “man” is the default and “wife” is just something he possesses.

There were many more, not just from the panelists who in a few instances disagreed on the cause of and the solutions to many of the issues. (Is religion a force for good or for ill in these matters? Yes? No? Ayo Sogunro argued, correctly I believe, that our imposition of a foreign belief system on what was a fairly equitable traditional family system complicated our gender relationships and gave excuse to men to relegate women into subservient roles because “the bible said so” or “it’s written in the Qur’an”. Femi Jacobs disagreed, crediting religion with all the good in the world and absolving it of the resulting ill. The followers of the faith, in his opinion, are the ones most responsible for the interpretation of simple harmless injunctions. This isn’t satisfactory, I argued, citing examples in Catholicism where divorce is frowned upon, and Islam where female genital mutilation is – in some cases mandatory. We cannot always separate religion from much of the problems we have with oppression and inequality in marriage, I said. It’s called “Man and Wife”, after all, and not “Husband and Wife”, where “man” is the default and “wife” is just something he possesses.