Here is a beautiful video by Femi Kayode Amogunla on names and contemporary attacks against it by ignorance and amnesia. Also, poetry, drums, and dance.

Read more about the artist here.

Here are my thoughts on the final story on the Caine Prize shortlist for 2013: Chinelo Okparanta’s America. Thoughts on earlier stories are here: Bayan Layi, Miracle, Foreign Aid and Whispering Trees.

_________________

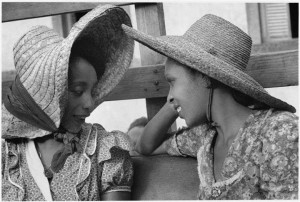

As far as the Caine Prize shortlist is concerned, no better gift could have come after last week’s unimpressive encounter with Whispering Trees than a story that is unpredictable, sweet, and delightful – a worthy end to my review of the five shortlisted stories of the Caine Prize 2013. In Chinelo Oparanta’s beautiful story of love and longing is that final elixir. It is a tale of love between two women, eventually separated by the other by the Atlantic Ocean, hence “America”, and a story-long attempt through a stream of recollections to reunite with the distant lover.

The story begins in medias res with the heroine Miss Nnenna Etoniru on the way to Lagos from Port Harcourt for a visa interview. She is hoping to head to America in order to meet Miss Gloria (whose age we didn’t quite figure out), a subject of her affection and love which had defied parental objection and entreaties. Before the trip is over, we hear about her first visit to the visa office which ended in a rejection. We also hear of the story of the relationship itself, how it began, who knew about it and what their reactions were, and what Nnenna was looking forward to in the nearest future. They had met in a school she worked, and where Miss Gloria had visited for a week, and struck up a relationship away from the eyes of their colleagues and the world. All through the story – and to great credit to the writer not falling into a temptation to write a treatise – the word “lesbianism” was never mentioned once. Instead we had the following:

The story begins in medias res with the heroine Miss Nnenna Etoniru on the way to Lagos from Port Harcourt for a visa interview. She is hoping to head to America in order to meet Miss Gloria (whose age we didn’t quite figure out), a subject of her affection and love which had defied parental objection and entreaties. Before the trip is over, we hear about her first visit to the visa office which ended in a rejection. We also hear of the story of the relationship itself, how it began, who knew about it and what their reactions were, and what Nnenna was looking forward to in the nearest future. They had met in a school she worked, and where Miss Gloria had visited for a week, and struck up a relationship away from the eyes of their colleagues and the world. All through the story – and to great credit to the writer not falling into a temptation to write a treatise – the word “lesbianism” was never mentioned once. Instead we had the following:

“Mama still reminds me every once in a while that there are penalties in Nigeria for that sort of thing.”

The “sort of thing” taboo-speak the author used here and elsewhere enhances the sense of the abominable in the relationship, leaving us to resolve our feelings about it ourselves. In another scene where her mother walks in on a live sexual scene taking place in Nnenna’s room, the writer describes it again as follows:

“Mama stands where she is for just a moment longer, all the while she is looking at me with a sombre look in her eyes. ‘So, this is why you won’t take a husband?’ she asks.”

It is subtle so that all concerned know what the mother had just witnessed. This dexterous show-not-tell style of writing greatly benefited the story, and deserves a lot of commendation. It also ensured that the story had just those (barely) two sexual encounters in order – I would guess – to keep it special/relevant enough to matter in our minds before it became all too gratuitous. In another scene, she describes something that seemed like a woman on her period:

“There is a woman sitting to my right. Her scent is strong, somewhat like the scent of fish. She wears a headscarf, which she uses to wipe the beads of sweat that form on her face. Mama used to sweat like that. Sometimes she’d call me to bring her a cup of ice. She’d chew on the blocks of ice, one after the other, and then request another cup. It was the real curse of womanhood, she said. Young women thought the flow was the curse, little did they know the rest. The heart palpitations, the dizzy spells, the sweating that came with the cessation of the flow. That was the real curse, she said. Cramps were nothing in comparison”

It turned out eventually that there was a literal fish somewhere in the woman’s bag, and that the woman herself was pregnant. It seemed to be a special narrative strength of the writer to put things like this, or else a personal quirk derived from her own inability or reluctance to be anything but discreet with intimate subjects. I found it enchanting.

In response to the earlier-quoted charge, Nnenna responds:

“It is an interesting thought, but not one I’d ever really considered. Left to myself, I would have said that I’d just not found the right man. But it’s not that I’d ever been particularly interested in dating them anyway.”

This is where my fascination with the plot begins. Many questions arise: was Nnenna a lesbian or merely bisexual? Was she capable of ever loving a man the same way she had loved Gloria? Was Gloria the last woman she would ever love (it certainly sounded like she was the first, or we would have been told)? Is it a love based on mutual respect of mental and professional capabilities and idealism, or one fuelled by lust and desire? Is it both? Will it endure or has it already begun to fail by the time Gloria returned home for the first time after her initial departure? Is this story about an expression of sexual orientation bursting out of a repressed environment or an expression of just a particularly stimulating and enduring passion developed serendipitously for one person only? Not all of these can be answered by the quote above, or by the story itself. At the end, we are left with the endless possibilities that abound in the reunion of two distant friends in a foreign land.

I am curious about these because the story is an important intervention in the current debate about same-sex relationships. From all we know, it was a consensual relationship. But from what we hear of the interventions of Mama, it was one caused by the overbearing influence of the foreigner which Nnenna just couldn’t shake.

I am curious about these because the story is an important intervention in the current debate about same-sex relationships. From all we know, it was a consensual relationship. But from what we hear of the interventions of Mama, it was one caused by the overbearing influence of the foreigner which Nnenna just couldn’t shake.

I found Mama‘s presence very interesting too: a Nigerian woman of the conservative Igbo culture whose strongest reaction to her daughter’s same-sex relationship was to cry a few times, and to pick out baby names in order to pressure the daughter. No church interventions. No village elders brought in. No shouting out loud until the whole town got involved and shamed the daughter. Either she is a weirdly tolerant modern Igbo/Nigerian mother, or she is a contrived flawless character that exists nowhere else but in Ms. Okparanta’s rebellious imagination. Either seemed to work perfectly, but I can accept this only because I am creatively wired to do so. It might be harder for others.

On the other hand, female-to-female sexual love seem to occupy a lower run on the outrage ladder of our society than male-to-male. The writer seemed to have acknowledged that reality in this scene, a nod to the more familiar types of Nigerian families we have come to always expect to meet in these kinds of situations:

‘You know. That thing between you two.’

‘That thing is private, Mama,’ I replied. ‘It’s between us two, as you say. And we work hard to keep it that way.’

‘What do her parents say?’ Mama asked.

‘Nothing.’ It was true. She’d have been a fool to let them know. They were quite unlike Mama and Papa. They went to church four days out of the week. They lived the words of the Bible as literally as they could. Not like Mama and Papa who were that rare sort of Nigerian Christian with a faint, shadowy type of respect for the Bible, the kind of faith that required no works. The kind of faith that amounted to no faith at all. They could barely quote a Bible verse.

‘With a man and a woman, there would not be any need for so much privacy,’

************

I enjoyed reading the story because of how it is written, error-free as you would expect from something in Granta, and the dimensions of politics, policy and advocacy that formed a humming background to the whole relationship. The right balance was struck to keep them visible enough, but not too loud as to crowd out the other details in the story. When the story is over, we forget about the oil spill and the other issues bedeviling Nigeria or the US, and are just contented that lovers are finally going to unite.

My grouse with America is with the title, an attempt to be plain and simple that ended up terribly as trite at best, and patronizing at worst. Out of about a million other titles that evoke love, expectations, guilt, distance, longing, and a thousand more other emotions one must feel while being in a taboo relationship fraught with such perils, Chinelo chose “America”, the biggest buzz-kill of all. The theme of “America”, “Americanah”, or traveling or returning has been written about so many times that inviting the audience into that story on that premise holds too much risk. I had the same problem and a disappointment of expectations with Pede Hollist’s “Foreign Aid”. One had to read the with a much reduced of expectations only to discover a gem in the end. That is too cruel, and doesn’t do justice to a work that could otherwise have enticed more curious readership and a better whetted appetite for such interesting stories.

_____________

Reproduced on Nigerianstalk LitMag | Photos from Actuatornic and Queer Cinema.

A couple of years ago, December 4, 2009, precisely, I wrote a blogpost in which I lamented a discriminatory practice in the blood donation system on the American campus where I was working then a visiting scholar. Because I was a Nigerian and for no other reason, I had been turned back from giving blood. Two years later, this time as a Masters student in the same university, I wrote a second report, acknowledging a change I noticed in the policy.

Since that first encounter, through the second one, the availability of blood (and the policies behind blood donation drives around the country) had remained on my mind as an abiding interest. So when, back in Nigeria, I was called into the founding of the One Percent Project and the Ten Thousand Donor project which both aim to make access to safe and healthy blood affordable and available through the means of information technology-driven applications, I jumped into it.

It had been fun, and enlightening, and rewarding. Since the founding of the organization in May 2012, the One Percent Project has helped facilitate the collection of about 754 pints of blood from young professionals from around the country, through the Nigerian National Blood Transfusion Service (NBTS) who then give it to hospitals where they are needed, thus potentially saving about 2262 lives (since a pint of blood is reputed to be able to save about three human lives).

It had been fun, and enlightening, and rewarding. Since the founding of the organization in May 2012, the One Percent Project has helped facilitate the collection of about 754 pints of blood from young professionals from around the country, through the Nigerian National Blood Transfusion Service (NBTS) who then give it to hospitals where they are needed, thus potentially saving about 2262 lives (since a pint of blood is reputed to be able to save about three human lives).

But that was just the beginning. So, starting from tomorrow June 14, the best tech volunteers, programmers and hackers from around Nigeria are gathering in Yaba and Lekki to collaborate with the One Percent Project to create an app that can make it easier for potential donors to link up with blood donation centres around the country, and especially for patients needing blood to connect with willing donors who have signed up to be called whenever the situation arises.

Tomorrow is also the 2013 World Blood Donor Day

I will be part of the event, tweeting nuggets, pictures, and thoughts via my twitter feed @baroka. At 4pm on Sunday, at the Audax Solutions Office (at Plot 24, Block 113, Adebisi Ogunniyi Crescent, Lekki Phase 1, Lagos), the app, called the LifeBank App, will be publicly launched. There will be bloggers, social media personalities, print media practitioners, and other trustees present. If you can make it, it would be nice to see you there too. It would be nice to introduce you to the advances this new generation of Nigerian youths are making to make the future much better than the present.

The LifeApp Facebook page has been set up, as well as a twitter page. Conversations on the hackaton and the app launch will be on twitter under the hashtags #hack4health and #LifeBank and on the LifeBank App blog.

This week, I discuss my thoughts on Abubakar Adam Ibrahim’s Whispering Trees, the fourth story on the shortlist of the 2013 Caine Prize for African Writing. Many other bloggers are participating in what Aaron Bady spearheaded as a “Blog Carnival”: thoughts and opinions on each of the shortlisted stories. Find the rest of the reviews on twitter via the hashtag #CainePrize.

_____________

Of all the stories I have read since this Caine Prize carnival began, Whispering Trees is one I have read twice fully, from beginning to end. It is a story about Salim, a young man who became disabled, and lost his eyesight, in a car accident and along with it his dignity and prospects, and who eventually finds a different kind of vision staring at “souls” of people, and seeing visions.

I read the story twice not because I particularly enjoyed and understood it all the first time, but because I didn’t fully grasp it and wanted to be sure about the intentions of the author and the character. Many of my thoughts from the first reading were confirmed by a second reading: it is a story about coping with disability, but a little also about faith, and psychic and supernatural outer body experiences, and love. The author doesn’t succeed in developing each of these areas, but we see that it was his intention that we see them. Away from the second reading, I realized that there were no hidden meanings other than the fact of the hero’s disabilities and eventual psychic evolution. It tried very hard to be didactic, but failed at that too. The last line, italicized for effect, read “I realize that happiness lies, not in getting what you want, but in wanting what you have.” I certainly had not come to that conclusion merely by reading the story, and including it as the last line did not drive it in either.

I could be uncharitable and say that Whispering Trees could have borrowed a leaf from the handling of the crises of faith and disability from reading Tope Folarin’s Miracle, or that it could have portrayed the homeliness of young hapless men under a tree deliberately named by reading Elnathan John’s Bayan Layi. Heck, it could have done better with romance under pressure by reading Pede Hollist’s Foreign Aid, but that would be assuming that the author wrote the story with the Caine Prize in mind, only after reading these other stories. It is most certainly not the case, so I will only say that whatever moved the author to write this story could most certainly have been better served by a shorter and smarter handling of the plot. There are many issues that can be raised from this story about of the helplessness of disabled people in Nigeria, particularly those wounded as a result of man-made disasters like car accidents. There are also angles of societal neglect and the non-existence of public facilities to make the life of disabled folks much easier. These however are from my own mining of the story’s schizzy fields. The author doesn’t consciously lead me to them.

The part of the story detailing the problems of disability were affecting, but seemed artificial and forced, helped by the tortured use of some figures of speech. The most uncharitable word for these instances of use is “amateurish”, providing a major obstacle to enjoying the story. Here are a few:

Personifications:

Sometimes it worked beautifully: “I remained there until my anger forced tears out of my damaged eyes”, but most times it didn’t: “Silence answered me.”, “Insomnia would claim me every night”, “My mind climbed up to the gates of heaven once more, seeking admittance”, “She would talk and weep until blessed sleep stole her away”, “I heard the trees screaming in agony as they were cut down”, and “But my mind was not very happy about this.” Nobody should ever write like that.

Similes:

There were some passable lines: “Her tears, like rain, fell on the wild fire of anger raging in my heart and extinguished it.” Others were not: “I discovered a whole new world of numbers and was as excited as Columbus must have been when he stumbled upon America” and “She pranced in front of the house calling for Saratu just like Achilles before the walls of Troy.”

Hyperbole:

In describing a rash and angry response of an otherwise reasonable citizen, the following was written: “Faulata fetched some petrol and poured it on the house. She was about to set it ablaze when they seized her. She struggled fiercely and wept because they would not let her burn down the house. Later, Saratu’s parents came to apologise. Neither Faulata nor I said a word to them. Then the elders came and delivered a long, boring lecture about forgiveness and reconciliation and, to get rid of them, I said it was over. So Saratu kept her distance.” The attempted arson described here could as well be the most hurried description I’ve ever read. I am trying to see how Faulata could have poured petrol on the house. The event to which Faulata was responding by trying to set a fire ablaze didn’t also seem to warrant this kind of response either, so I chalked it down as a failed hyperbole regarding plot.

In another part of the story, a character makes an attempt at quoting Oscar Wilde. The original poem, from The Ballad of Reading Gaol, reads:

Yet each man kills the thing he loves

By each let this be heard.

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word.

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!

In Ibrahim’s story, there was the following:

Hamza and I talked some more until he rose and said, “I must leave now. Now that you are here, I can leave. But see how beautiful this place is, see how pure and full of life it is. Yet, someday, the living will come and destroy everything.” He started off, “Man destroys that which he claims to love.”

In another instance, the author tries to write in Nigerian Pidgin English, yet gave us the following:

The oga’s voice was raucous. “How much you find for ’im body?”

The first man said, “Four thousand naira, sir.”

The oga grumbled, “These ones se’f, them no carry plenty money. Oya, put ‘im body with the others but hide the money before people come.”

Yes, that was ‘im body, se’f, and other unconvincing attempts at Nigerian Pidgin. In pidgin, there would be no apostrophe in any of those words, and “body” would surely have been written as bodi.

I realize then why I found the story hard to enjoy as fiction, or anything other than the writer’s attempt to be profound and didactic with magical realism: it tried too hard, with little skill, and failed (at least as a worthy representative of this year’s shortlist of the best of African fiction. As some have wondered aloud: “thank goodness we won’t have to read the other ninety non-shortlisted pieces!”).

Now, so that this does not end up as a completely disappointed rant against something that Mr. Ibrahim surely put a lot of effort into writing, let me admit that I found the first sentence quite charming and inviting: “It’s strange how things are on the other side of death.” Had the promise of that initial sentence been followed by equally strong and well sustained passages, and had the story been a lot shorter, or at least the characters better developed, we might have had a different offering.

The other paragraph that I found absolutely delightful is as follows:

“The rains came and went. The grasses grew lush green and faded into a pale, hungry brown. I could hear the dry, cold harmattan winds blowing through the starved savannah; I could feel it on my desiccated skin. The weather grew unpleasantly chilly. Everything was cold, including my heart. Faulata was gone”

Unfortunately, gems like this were far in-between, and did not tie the story together as a tale of resurrection, redemption, and a soulful realization of an inner strength and power as the author clearly intended the story to be.

___________

Also published on the NT LitMag

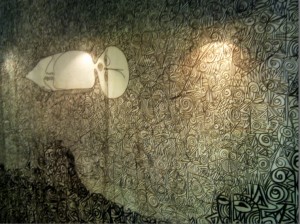

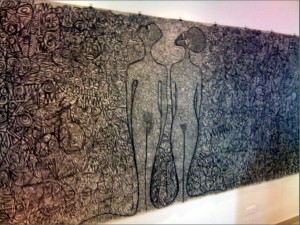

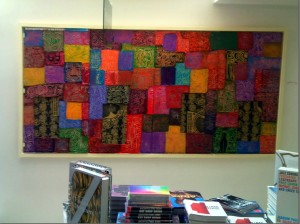

Here are photos taken at the exhibition of photos and paintings by Nigerian artist Victor Ehikhamenor.

Here are photos taken at the exhibition of photos and paintings by Nigerian artist Victor Ehikhamenor.

The exhibition, titled Amusing the Muse, took place between April 27 and May 31, 2013, at Temple Muse, 21 Amodu Tijani street, Off Sanusi Fafunwa, Victoria Island, Lagos.

The artworks beautifully arranged around the premises of the Temple Muse (which is also an events shop, bookstore, and a fashion & lifestyle showroom), were given names like “I don’t know where to but let’s go”, “To all the first ladies who love themselves”, “Coup plotter before shower”, “Your head is correct”, “Home sweet home”, “Mr president after the coup”, “Adam and Eve waiting for a flight out of Eden”, “Your dancing is music inside my head”, “Yesterday and today waiting for tomorrow.”, “Your music is dancing inside my head”, “Nobody came to us”, and “Opportunities in the land of closed doors”.

Of form, the work varied from “Charcoal on canvass” to “Paintforation on handmade paper”, “Charcoal and oil pastel on canvas”, “Ink wash and acrylic on paper”, “Latex paint and charcoal on handmade paper”, and “Acrylic on wood and fabric”.

My interview with Victor has just been published at NigeriansTalk.