by Torinmo Salau

I got to Oshodi few minutes past 7am, my plan was to take off from Lagos before 6:30 Am. Rather I found myself panting under the weight of the Khaki travel bag strapped to my back, frantic to get on the next vehicle en route Kuto, Abẹ́òkuta which finally set out few minutes to 8am.

The grey Sienna car was badly dented and its rear windscreen had a slight crack which ran diagonally across its full length. The vehicle moved swiftly, faster than I even envisaged and within 30 minutes, we were approaching the tollgate. With Ma Lo by Twa Savage and Wizkid playing quietly in the car, I tried to go through the Aké Festival program schedule on my Samsung tablet.

“Are you going to Aké too?” the husky voice who sat beside me asked, jolting me out of the thoughts which clouded my mind.

“Yes”. I wondered why he was smiling sheepishly and from the way the words rolled off his tongue, you could guess his name would either be Emeka or Ifeanyi. But I did not guess right, his name was Chike.

After conversing for some minutes, I discover that Chike is a lawyer but he daylights as a freelance writer and editor.

“Shit I forgot my drugs,” he said midway through the conversation, mumbling words I barely understood.

“I forgot my antidepressants, he continued, sounding more distressed with anxiety ripping slowly through his face. His anxiety was palpable as he shifted from left to right in his seat, visibly shaken from the reality which just dawned on him.

“Are you depressed?”

Then I realized that was a dumb question to ask, if he is not suffering from depression, then why is he is shaking like a crinkled leaf which has lost its moist to the parched harmattan wind.

Then I realized that was a dumb question to ask, if he is not suffering from depression, then why is he is shaking like a crinkled leaf which has lost its moist to the parched harmattan wind.

“Yes, I am depressed. But I will be fine without the drugs, he said shrugging his shoulder limply. Then he turned his back towards me, looking out of the window and staring at lush green vegetation which lined the road.

We were way past Mowe-Ibafo and its environs, I knew this because there was no sight of human habitations along the road again, just signposts after signboards and signages which had rusted and were barely legible to read.

“Sorry to hear, you are suffering from depression.”

I said the word ‘Depression’ almost inaudibly, carefully curating every word I spoke like somebody walking on eggshells, eggshells which can crack just by the slightest omission of a letter.

“Please don’t be, Chike said looking away from the window, smiling, I guess he was trying to hide his disappointment.

“I get a little cranky when I miss my medication but I will be fine, it’s just for two days”.

This was the second time he was saying, “I will be fine” within the space of five minutes.

While he sounded fairly reassuring, I still felt worried. Worried by the fall in his countenance and the dark shadow cast over the bubbly persona he exuded at the onset of the journey. Wondering what the resultant effect of missing a pill or two could be, wondering why he had to repeat himself if he would really be fine?

Then the journalist in me kicked in.

“How long have you been feeling depressed?” I asked with my curiosity etched up, hungry to dig down the layers of this story, hoping it is not what I think it is.

“Two years thereabout”.

“Besides antidepressants medication, why didn’t you explore other means of managing this condition?”

“I did. I tried therapy first but it was quite expensive. Then I switched to a psychiatrist, the doctor placed me on drugs which have been more effective than therapy”.

“But contrary to what I am aware of, therapy works best, better than tying your daily existence to a bottle of pills?”

“Yes it does, for some people. But the antidepressants help to balance my moods, keeps me from bouncing from one end to the other.

“Are there any side effects to antidepressants?”

“Yes of course, especially the withdrawal symptoms which varies among individuals, ranging from anxiety, insomnia, nausea, fatigue amongst others. It can either be mild or severe.

Chike turned his back to me again, but this time, he wasn’t looking out of the window. Rather, just staring at the brown threadbare carpet on the floor of the car, which was caked with red sand. By then the song playing in the car was ‘Joromi’ by Simi, with light chatter from fellow passengers, some talking about the Spanish La Liga while others were lamenting the epileptic power supply across the country. But for few seconds, there was a transient suppression of verbal expression. The gulf of space between us was taken up by silence and it stood there for what seemed like an eternity.

Chike turned his back to me again, but this time, he wasn’t looking out of the window. Rather, just staring at the brown threadbare carpet on the floor of the car, which was caked with red sand. By then the song playing in the car was ‘Joromi’ by Simi, with light chatter from fellow passengers, some talking about the Spanish La Liga while others were lamenting the epileptic power supply across the country. But for few seconds, there was a transient suppression of verbal expression. The gulf of space between us was taken up by silence and it stood there for what seemed like an eternity.

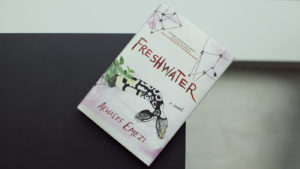

Though I pretended to read a book, Chike’s words kept throbbing my mind. His mental health struggles mirrored exactly what I was going through but what I was also denying and the more I looked in, the more I saw a reflection of myself.

On some days, I am just floating through space, watching my life from a distance as my dreams and ambitions vapourize into thin air, without any drive to rescue them. Though I feel sparks of euphoria and drift to a different time space with my heart clustered with sugary fantasies tickling my taste buds, it is not for too long. Reality always lingers and thoughts of pulling the trigger moonwalk across my mind often. I want to run away, yet I am too scared to die.

I was excited as the car approached the ‘Welcome to Ogun state’ signboard. I could feel its momentum rising to 120KM/H, as the driver drove past the Governor’s Office which was painted in the colours of the national flag, heading into town.

***

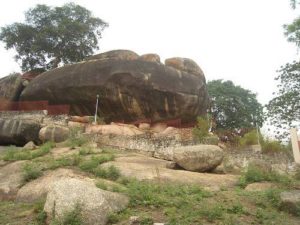

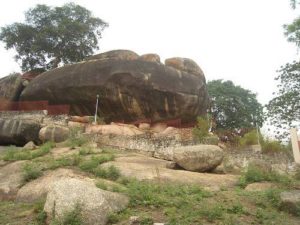

While this was my second visit to Abẹ́òkuta, the city of rocky hills within the space of a decade, it was my first time at the Ake Book and Arts Festival, the fifth edition of AKEFEST. An annual literary, art and cultural event which pools authors, creatives, writers, artists, musicians, activists to share their work and ideas. It is no doubt a booklover’s dream as it offers the opportunity to interact with some of the major voices in the contemporary African literary scene.

While this was my second visit to Abẹ́òkuta, the city of rocky hills within the space of a decade, it was my first time at the Ake Book and Arts Festival, the fifth edition of AKEFEST. An annual literary, art and cultural event which pools authors, creatives, writers, artists, musicians, activists to share their work and ideas. It is no doubt a booklover’s dream as it offers the opportunity to interact with some of the major voices in the contemporary African literary scene.

I found the theme for the 2017 edition of Ake Festival, ‘This F-Word’ really intriguing, this was undeniably a profound time to have this conversation and stanchly confront the issues revolving around it. But the big cherry on the cake was the headliner for the event, Ama Ata Aidoo. Renowned poet, novelist and feminist. My favourite amongst her books is Anowa, a Ghanaian play about a young girl who rejects suitors proposed by her parents and marries a stranger, Kofi Ako. Kofi is angered by Anowa’s attitude of being a modern women and asks her to leave when she could not conceive a child. But Anowa discovers later that her husband had lost his ability to bear children, so the fault was his not hers. This discovery of the truth forces Kofi to shoot himself while Anowa drowns herself.

The trip ended at Kuto, it lasted for about 90 minutes. As luck would have it, the location of the literary festival, Arts, and Cultural centre was situated right beside the bus park, along Ibrahim Babangida Boulevard, Kuto. Chike and I were the last passengers to highlight from the car, I mumbled a short prayer to the heavens, grateful for the miracle of surviving the road.

Though the literary festival was a weeklong event, precisely five days from November 14th – 18th, 2017, I arrived at AkeFest on Day 4, Friday, hoping to still maximize the best of the event within the last two days. Chike and I exchange phone number and parted ways, promising to stay in contact with each other. He wanted to hear Toni Kan speak but I ran off to the current session underway, Book Chat with Alexis Okẹ́owó and Dayọ̀ Ọlọ́pàdé.

Storytelling with Mara Menzies on The illusion of the Truth was an enthralling moment as she told a Kenyan story of how Gikuyu women were not permitted to eat meat. Mara’s undulating body rhythm and the subtle tenor in her voice added more spice to the story. The fork in the road was one woman’s search for the truth and determination to fight the cultural stereotype which beleaguered women in her community. The day ended with a stage play by Yolanda Mercy on Quarter Life Crisis, a monologue which mixes expressions of spoken word and addictive baselines infused with a side dish of comedy. Most individuals go through a quarter-life crisis, but they don’t know it. Just like Alice, the main character in the story, we are swiping from left to right. Young, exuberant yet confused, not knowing what to do with the blank cheque called life, given to us. Though everyone around her thinks they know where they are going in life, the stage play which shows Alice trying to find ways to cheat growing up ends with a hilarious climax. However it doesn’t end without asking the audience with these two questions, ‘What does it mean to be an adult?’ and ‘When do you become one?’

Dusmar Hotel

I retired for the night at Dusmar Hotel, situated next to the Art and Cultural centre which saved me an extra cost of commuting within Abeokuta to the literary event. The hotel’s reception struck me with a major throwback to the mid-90s, refreshing fragments of my memory littered here and there. The furniture and furnishings were quite antique. The windows, still the same old model fitted with louvres reminded me of an incident I did not want to remember and I would rather not talk about it. But I found myself wondering why a hotel bore this type of window fittings even in the year 2017, though mildly nostalgic yet largely traumatizing.

I retired for the night at Dusmar Hotel, situated next to the Art and Cultural centre which saved me an extra cost of commuting within Abeokuta to the literary event. The hotel’s reception struck me with a major throwback to the mid-90s, refreshing fragments of my memory littered here and there. The furniture and furnishings were quite antique. The windows, still the same old model fitted with louvres reminded me of an incident I did not want to remember and I would rather not talk about it. But I found myself wondering why a hotel bore this type of window fittings even in the year 2017, though mildly nostalgic yet largely traumatizing.

Day 5, Saturday, the event was winding down but more people were still pouring it. As the literary festival teetered towards its climax, everything became fast paced. People frantically buying discounted books and F-Word books from the bookshop. The flashlight of cameras everywhere you turned to, as people tried to seal the memories and friendships formed within the space of five days. There was a book signing spree, authors inking their thoughts on books purchased by readers and their fans which was consummated with the millennials’ trademark autograph, Selfies!

My highlight of the day was the Life and Times session on Ama Ata Aidoo. The renowned author who has been writing for over sixty years spoke liberally about her life, work and feminism. It was an emotionally charged atmosphere for many in the hall as she paid an emotional tribute to Mariama Ba, Flora Nwapa, Buchi Emecheta and other women pioneers of African writing.

“I hope you will extend the love and appreciation, you have shown me to my sister writers – living and past.” But what stuck with is the last line of one of the poems she read, “A girl’s voice doesn’t break, it gets firmer.”

***

I returned to Lagos on Sunday morning with a belly full of feisty aspirations, determined to change my misconceptions about feminism. Also to commit myself to unlearning and relearning, as the words of Mona Elthaway persistently rings in my ears, ‘Fuck the Patriachary’. Part of the main insights gained from the Ake festival is the universality of our experience as women whether black, white, or queer and why it is critical to challenge the elephant in the room, especially peculiar societal norms and beliefs which have repressed us decades.

____________

Torinmo Salau’s work has been published online and offline in literary publications, magazines, and anthologies.